Anna Evans Murray (1857-1955) was a racial justice activist, day nursery and kindergarten advocate, and educator whose contributions to advance public kindergarten focused on Washington, D.C. (Smith, 1996).

In the national public kindergarten movement, the District of Columbia was one of the shining examples of successful efforts to secure public funding. The $12,000 allocation for the district’s public kindergartens approved by Congress with the 1898-1899 appropriations act is repeatedly mentioned in an early report detailing highlights from the city (Association for Childhood Education International, 1939). However, the process to secure public funding, the role of Black women’s leadership, and the national Black women’s movement undergirding these efforts was not noted by the Association of Childhood Education International (ACEI). Although earlier histories attribute the congressional appropriations to White women (Vandewalker, 1908), more recent and influential works credit Anna Murray for her leadership (Beatty, 1995; Allen, 2017).

In this profile, we take a deeper dive into Murray’s trajectory as a public kindergarten advocate in the context of early childhood education’s broader history. Anna Murray’s story not only demonstrates the importance of public funding for early learning’s sustainability and growth, but also underscores the challenges of providing training for Black teachers. As Black kindergarten advocate Haydee B. Campbell saw in St. Louis, early public kindergartens in Washington, D.C., were denied, delayed, or segregated for Black children. Murray’s advocacy of public kindergartens for Black children also included a crucial parallel strategy to train Black kindergarten educators

Anna Murray graduated from Oberlin College in 1876, one year before the end of Reconstruction (Smith, 1996). She moved to Washington, D.C., to begin her lifelong career as an educator, briefly teaching music to college students at Howard University followed by several years teaching third- and fourth-grade students at the Lucretia Mott School (Taylor, 2017; Smith, 1996). Murray came from an activist family that supported Black freedom as participants in the Underground Railroad as well as abolitionist John Brown’s 1859 insurrection at Harpers Ferry (Smith, 1996). She married Daniel Murray, an assistant librarian at the Library of Congress, with whom she had seven children, five of whom lived to adulthood (Smith, 1996).

Murray was active in the Colored Women’s League (CWL), organized in Washington, D.C., in June 1892 and incorporated in January 1894 (Brooks, 2018). The CWL was committed to consolidating the power of Black women to address racial and gender injustice through a variety of activities, often with a focus on education, such as day nurseries for working mothers and night schools for adults (Brooks, 2018). Murray began her role as CWL’s Education Committee Chair in 1895 (Smith, 1996) and the Kindergarten Committee Chair in 1898 (Brooks, 2018). An 1896 merger between the CWL and National Federation of Afro-American Women created the National Association of Colored Women, which became the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs (NACWC) upon its incorporation in 1904. The CWL continued its local activities in the District of Columbia, where Murray’s work was focused (Brooks, 2018).

Murray described the CLW’s first annual convention in 1896 as the turning point that persuaded the CWL to focus on kindergarten efforts: “…as I listened to the earnest words of the noble women from all over our country who came bringing the results of efforts put forth for the elevation of the womanhood of the race, it seemed to me that there was one safe, sure guide in an effort to remove the cause of the many accusations that have been made against us [as] a race” (Murray, 1900, p. 504). When the executive board told Murray that the recent convention limited resources for kindergarten work, she took matters into her own hands: “[I] asked permission to develop what I could” (Murray, 1900, p. 502). After learning of a kindergarten soon to close, Murray made a request for the cast-off tables and chairs and was also given the use of the building and janitor’s services free of charge. The executive committee accepted the gifts secured thanks to Murray’s ingenuity and resourcefulness, and the CWL members provided funding from their personal resources for Murray’s efforts (Murray, 1900). The CWL’s kindergarten work had begun.

In 1896, Murray opened two kindergartens: one afternoon session for poor and working-class families (charged a penny a week) and one morning session for well-resourced families (charged fifty cents a month) (Murray, 1900, p. 505). The CLW would eventually expand to six or seven private kindergartens (Smith, 1996). Building on the Black community’s interest in establishing kindergartens in the district as early as 1883 (ACEI, 1939), Murray and the CLW readied the soil for planting kindergartens in public schools by establishing these first private kindergartens. In the process, she realized that establishing accessible kindergartens was one challenge, but the limitations facing Black kindergarten teachers were another.

Washington, D.C., 1908

The prohibitive cost of private training was a barrier for Black and working-class women who wanted to become kindergarten teachers. Limited access to training also hindered the ability of Black communities to build the teacher workforce necessary for expanding early education services. By 1898, 19 states contributed public funds to establish courses on kindergarten in state-run teacher training schools, referred to as Normal schools. However, even when publicly funded, Normal schools were typically segregated, denying access to Black women.

Although she initially hired a White kindergarten teacher out of immediate necessity, Murray expanded her efforts to train Black teachers, linking public kindergarten expansion to the institutionalization of Black teacher training: “I wrote to Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago, to obtain a colored [kindergarten teacher], but the very few prepared were more profitably employed at home. Out of the dearth of women of the race prepared for this field of labor arose the necessity for training teachers of our own, and I immediately cast about to make this possible” (Murray, 1900, p. 505, emphasis added). She used $450 of her personal resources to contract a White kindergarten trainer, who agreed to train 15 young Black women who practiced their observation and teaching skills at the CWL kindergarten (Murray, 1900). To sustain the training program, which often relied on tuition for funding, Murray needed to secure private donations to ensure access for Black women. At the 1898 Congress of Mothers Convention, Murray connected with Phoebe A. Hearst, widow of former California Governor George Hearst and a well-known philanthropist who supported kindergartens throughout the country (Ross, 1976). Murray successfully secured Hearst’s patronage for the training school for five years (Smith, 1996). In 1899, the training school graduated 28 young Black women as kindergarten teachers (Murray, 1900).

Next, Murray sought “seed money” from Congress and the support of local government: “As soon as our training department was in working order and our model school running smoothly, I advised that we knock at the door of our municipality and ask that kindergarten be made a part of our public school system” (Murray, 1900, p. 505). Although other sources do give her credit for the success of the D.C. kindergarten appropriations (Beatty, 1995; Allen, 2017), Murray’s 1900 Hampton Address, published in The Southern Workman, tells the story in her own words, describing the fits and starts of the process.

“The work of making the kindergarten a part of the school system is only a question of time. The most eminent educators of the day recognize and endorse its principles and methods, but the expense involved prevents its becoming at once the lowest grade of the public school system.”

U.S. Bureau of Education, 1887, p. 333

Kindergartens in the United States: Roots of Delay, Denial, and Inequity

While kindergarten expansion accelerated in the last decades of the 19th century, by 1898 less than 5 percent of children participated in such programs (Beatty, 1995).1By 1912, only 9 percent of children age four to six were enrolled in public or private kindergarten (U.S. Bureau of Education, Department of the Interior, 1914, cited in Williams & Whitebook, 2021). A decade later, participation in kindergarten had only increased to 11 percent (U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Education, 1921). Then as now, access to early learning depended on a child’s age, their race, and where they lived. Despite consensus that all children would benefit from the kindergarten experience, politics and policy determined whether three- to six-year-olds (the original population served by kindergarten programs) would have the opportunity to participate in any program and, if so, whether it would be operated by a private organization or the local public school (U.S. Bureau of Education, 1899). Even in states with more public provision, kindergarten opportunities for Black children were delayed, outright denied, and almost always segregated (Austin, Whitebook, & Williams, 2021; Williams & Whitebook, 2021).

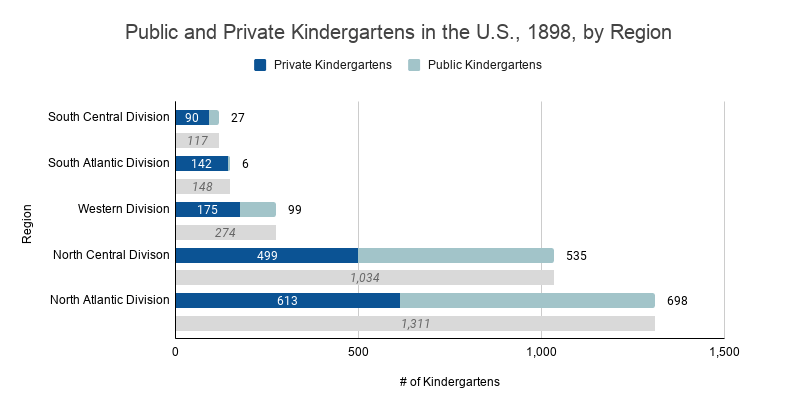

In 1897-1898, for example, most kindergartens (81.4 percent) were located predominantly in cities in the North Atlantic (45.5 percent) and North Central (35.9 percent) states. Less than 10 percent of public and private kindergartens combined were located in the South Atlantic (4.1 percent) and the South Central (5.1 percent) states. Significantly, 90 percent of the Black population resided in these southern regions, typically in rural communities where provision remained sparse for decades.2The 1930-1932 Biennial Survey of Education reported the slow expansion of kindergarten in rural communities: “In urban areas, 1 of every 22 pupils attending the schools is enrolled in kindergarten; in rural sections, only 1 pupil of every 147 enrolled is registered in kindergarten” (U.S. Department of the Interior, Office of Education, 1935, p. 65). Only 2.5 percent of public kindergartens in the United States were located in the southern states, and most served White children exclusively (U.S. Bureau of Education, 1899).3Only three states in the combined Northern regions (Vermont, North Dakota, South Dakota), did not provide public kindergartens in the 1897-1898 school year, while more than half the states in the Southern regions reported no public school kindergartens. In the South Atlantic region, no public kindergartens were established in Delaware, Maryland, or North Carolina, and West Virginia did not provide either type of kindergarten. Funding was allocated for the District of Columbia’s public kindergarten during 1897-1898, but children were not served until the 1898-1899 school year. In the South Central regions, no public kindergartens were established in Arkansas, Tennessee, or Oklahoma, and only one private and no public kindergartens were available in what were then called the “Indian Territories” (the portion of the South Central United States that members of the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole Nations inhabited following their removal from their tribal homelands in the 19th century and incorporated into Oklahoma when their quest for statehood was denied in the early 20th century). The sparsely populated Western region, home to a higher concentration of the Latinx and Indigenous populations, claimed 9.5 percent of the nation’s kindergartens, but only California and Colorado offered public kindergartens. Those two states also offered private kindergarten, as did Montana, Oregon, Utah, and Washington. The states of Arizona, Idaho, Nevada, New Mexico, and Wyoming had no provision for kindergarten (U.S. Bureau of Education, Department of the Interior, 1899).

Source: United States Bureau of Education, 1899.

Public policies shaped enduring disparities in kindergarten access as states began to pass laws governing age of entry, financing, and teacher preparation for public kindergartens. Sixteen states and the District of Columbia had kindergarten laws in 1889: of the 13 states specifying age of entry, one set the age at five, nine set the age at four, and three states allowed children as young as three years of age to attend kindergarten (U.S. Bureau of Education, 1899). Restricting younger children from participating was an effective way to control costs and eventually would drive up the age for kindergarten in all states (Beatty, 1995; Allen, 2017; Education Commission of the States, 2020). As late as 1931, however, 25 states still permitted four-year-olds to attend public kindergarten, and a few states even allowed three-year-olds (U.S. Department of Interior, Office of Education, 1931).

In most states, laws were necessary to permit young children to be educated at public expense, but few states incorporated kindergarten into their state school funding scheme. Most public kindergartens relied almost entirely on local tax revenue, often distinct from other school levies. Public kindergartens were particularly vulnerable to cuts and elimination, and even private kindergartens failed to survive during tough economic times.4The 1930-1932 Biennial Survey of Education remarked on the vulnerability of kindergartens early in the Great Depression compared to services for older children, noting that the economic situation “affected kindergarten enrollment earlier than other types of public schools, and therefore, there were fewer children in kindergarten in 1932 than in 1930” and also indicated that the “decrease in kindergarten enrollment is due partly to changes in the age of admission [and also] to curtailments in the number of kindergartens within school systems and, in some cases, to their elimination” (U.S. Department of the Interior, Office of Education, 1935, pp.16, 145). These early laws established a precedent for differentiated and inadequate funding for early learning programs serving children of different ages. As a consequence, early learning programs for children under age five remained mostly under private provision, rendering public pre-K for all three- and four-year-olds a problem to solve for another century (Austin, Whitebook, & Williams, 2021).

When she testified before the appointed congressional committee, their priority question revealed the racial challenges of funding Black kindergartens: “The first question asked me by one of the commissioners was, ‘Where will you get teachers for your colored schools?’” (Murray,1900, p. 505). The training school Murray had already established provided the structure to address these concerns of segregated teaching forces for segregated schools. The commissioner was “pleased to know this,” and after interviewing the Black and White superintendents of D.C. schools, the committee recommended allocating $12,000. However, Congress failed to appropriate the funding due to its short session and lack of time.

Yet, Murray persisted: “[N]othing daunted, I again sought for another recommendation and followed it to the halls of Congress” (Murray, 1900, p. 506). Despite her determination, the recommendation was thrown out. The third time, Murray was invited by Senator Mitchell of Wisconsin to bring a small group of women from the CWL to testify for favorable consideration. However, on the day the group was set to testify, Murray was on her own: “[B]oth the other women deserted me, pleading engagements, and I was obliged to appear before the senators alone. With fear and trembling, but strong in my cause, I made a plea which touched their hearts” (Murray, 1900, p. 506).

This time, Murray’s efforts on behalf of the CWL were successful in securing $12,000: $8,000 for White schools and $4,000 for Black schools, allocations Murray suggested were in proportion to the population of each racial group. In her speech, Murray charts the growth of appropriations from Congress: $15,000 in 1899 and $25,000 in 1900. Like many early childhood advocates who witnessed the transformations flowing from their efforts, her expectations for the future were optimistic: “I expect to see it reach the $75,000 mark in the next six years” (Murray, 1900, p. 506). The hoped-for level of funding was not reached until the 1908-09 academic year, but in 1906, Murray was responsible for the new appropriations’ inclusion of kindergarten training courses for Black women at Miner Normal (later Miner Teachers College, now the University of the District of Columbia) as well as funding for a White Normal school (Smith, 1996; Washington, D.C., Board of Education, 1911).

After she secured public funding for kindergarten in Washington, D.C., Murray put her “strongest energy toward planting it in the Southland’’ (Murray, 1900, p. 506; Murray, 1904). Murray’s vision for southern expansion was multifocal and consistent with her previous work: laying the groundwork for scaling training programs for Black women and urging the federal government to provide funding (Murray, 1900). She planned to bring 25 women from Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) — including Hampton, Tuskegee, Atlanta, Fiske, Shaw, and Straight Universities — to her kindergarten training school, covering tuition costs and providing room and board for the duration of their studies (Murray, 1900). As an expansive visionary, Murray planned a bill to appropriate $14 million from the U.S. Treasury, secured through “the sale of captured cotton and abandoned lands during the late civil strife,” for public kindergartens in 14 southern states (Murray, 1900, p. 507). We imagine that this redistributive vision speaks partly to the hope experienced by Black people who lived through Reconstruction and to her belief in the power of the pedagogical possibilities of kindergarten.

The scope of Murray’s vision for public funding for kindergarten in the South can be tied to how she viewed the home and education as a necessary part of the fight to end racial prejudice. She felt that “statutes on the books” were limited without changes through education (Murray, 1904). We imagine that Anna Evans Murray’s vision, drive, and optimism about the power of education were deeply informed by her coming of age during Reconstruction and her family history of activism (Smith, 1996). Her own legacy is rooted in her twofold approach that utilized her abilities to “develop what she could’’ in the immediate moment (Murray, 1900), while dreaming and thinking big about what must be built to create more just Black futures through education.

Murray pursued the struggle to secure opportunity and justice for Black children well into her ninth decade. Recognized for her lifelong contribution to many communities, she remained a venerated member of the District of Columbia’s early childhood community. For her 85th birthday, a celebration of her life was organized by kindergarten teachers, and for the remainder of her 97 years, the early childhood community acknowledged her contributions each year on her birthday (Smith, 1996). In her own words, we see that she viewed kindergarten as a powerful educational project:

“As soon as the kindergarten training for women as teachers shall have become a part of the curriculum of Negro colleges, high, and normal schools, then the wealth of maternal instinct which abides in the heart of the Negro woman will be turned into insight and make her invincible in her own demand that her children shall be trained aright. Let the great mother heart of the nation rise to its opportunity and make possible for the children and the children’s children a nearer approach to the glorious ideal for which Democracy stands”

(Murray, 1904, p. 234).

District of Columbia: A Century of Leadership in Public Early Learning

In Washington, D.C., as in most cities, provision of public kindergarten fell short of its early aspirations. When public kindergartens opened in 1889, following the successful advocacy by Anna E. Murray and others, only five-year-olds stepped over the threshold into separate classrooms for Black and White children. The D.C. school board trustees deemed it “safer to restrict the entrance age at five years” and proclaimed that “when all of the five-year-old children in a given neighborhood had been provided for, the admission of young children was permitted” (ACEI, 1939).

Stable funding from Congress, a source available only to the District of Columbia owing to its unique status, provided a sturdy foundation for the growth of local kindergartens. By 1920, 39 percent of the district’s age-eligible children attended kindergarten, more than triple the national average of 11 percent and six points higher than California, the highest-ranking state with 33 percent of age-eligible children enrolled in kindergarten (U.S. Department of the Interior, 1921). By 1938, Washington, D.C., could boast a kindergarten “in nearly every elementary school building or group of buildings, and in some crowded neighborhoods, there are two kindergartens in the same building” (ACEI, 1939).

Nonetheless, evidence suggests that disparities existed between White and Black kindergartens, which like the D.C. schools overall became increasingly segregated and unequal in the decades after Reconstruction ended (ACEI, 1939). In their 1908-9 Annual Report, the Commissioners of the District of Columbia noted the average cost per year of White kindergarten pupils as $41.68 compared to $37.11 for Black students (Washington, D.C., Board of Education, 1911). Such differences persisted over time. In their 1915 Annual Report, the Commissioners note that the teacher/child ratio for Black children was 1 to 37, compared to a ratio of 1 to 26 for White children (Washington, D.C., Board of Education, 1916).

In 1970, the District of Columbia allocated initial funding for pre-kindergarten for four-year-olds, but when the 2008 D.C. Council passed the Pre-K Enhancement and Expansion Amendment Act, they renewed their long-standing goal to serve not only all four-year-olds in public programs, but three-year-olds, as well. In 2019, the District of Columbia enrolled 83 percent of four-year-olds and 78 percent of three-year-olds in public pre-K, a higher percentage than any U.S. state or territory. Nationally, on average, 38 percent of four-year-olds and 6 percent of three-year-olds are enrolled in state-funded preschool programs (Friedman-Kraus et al., 2020).

References

Allen, A.T. (2017). The Transatlantic Kindergarten: Education and Women’s Movements in Germany and the United States. Oxford University Press.

Association for Childhood Education International (ACEI) (1939). History of the Kindergarten Movement in the Southeastern States and Delaware, District of Columbia, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. Association for Childhood Education International.

Austin, L.J.E., Whitebook, M., & Williams, A. (2021). Early Care and Education is in Crisis: Biden Can Intervene. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. https://cscce.berkeley.edu/blog/2021/01/21/ece-is-in-crisis-biden-can-intervene/.

Beatty, B. (1995). Preschool Education in America: The Culture of Young Children from the Colonial Era to the Present. Yale University.

Brooks, R. (2018). Looking to Foremothers for Strength: A Brief Biography of the Colored Woman’s League. Women’s Studies, 47(6), 609-616.

Education Commission of the States (2020). 50-State Comparison: State K-3 Policies. https://www.ecs.org/kindergarten-policies/.

Friedman-Krauss, A.H., Garver, K.A., Hodges, K.S., Weisenfeld, G.G., & Gardiner, B.A. (2020). The State of Preschool 2019. State Preschool Yearbook. National Institute for Early Childhood Education Research. Retrieved from https:// nieer.org/state-preschool-yearbooks/2019-2.

Murray, Anna E. (1904, April). In Behalf of the Negro Woman. The Southern Workman, XXXIII(33), pp. 232–234.

Murray, Anna J. (1900, July). A New Key to the Situation. The Southern Workman, XXIX(1), pp. 503-507.

Ross, E.D. (1976). The Kindergarten Crusade: The Establishment of Preschool Education in the United States. Ohio University Press.

Smith, J.C. (1996). Notable Black American Women. Gale Researcher.

Taylor, E.T. (2017). The Original Black Elite: Daniel Murray and the Story of a Forgotten Era. Amistad.

U. S. Bureau of Education. (1887). Report of the Commissioner of Education for the Year 1885-’86. U.S. Government Printing Office. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/coo.31924067337380

United States Bureau of Education (1899). Report of the Commissioner of Education for the Year 1897-98, Vol. 2. U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951d000234888.

United States Department of Interior, Office of Education (1931). State Legislation Relating to Kindergartens, 1930-1932. No. 30. U.S. Government Printing Office.

United States Department of the Interior, Office of Education (1935). Biennial Survey of Education, 1930-1932. Bulletin 1933, No. 2. U.S. Government Printing Office.

United States Department of the Interior, Bureau of Education (1921). Kindergarten Education 1918-1920. Bulletin 1921, No. 19. U.S. Government Printing Office.

Vandewalker, N.C. (1908). The Kindergarten in American Education. Macmillan.

Washington, D.C., Board of Education (1908-9). Annual Report of the Commissioners of the District of Columbia, Vol. 4, Report of the Board of Education. U.S. Government Printing Office.

Washington, D.C., Board of Education (1911). Annual Report of the Commissioners of the District of Columbia, Vol. 4, Report of the Board of Education, Year ended June 30, 1909. U.S. Government Printing Office.

Washington, D.C., Board of Education (1916). Annual Report of the Commissioners of the District of Columbia, Vol. 4, Report of the Board of Education, Year ended June 30, 1916. U.S. Government Printing Office.

Watson, B.H. (2010). A Case Study of the Pre-K for all D.C. Campaign. Foundation for Development.

Williams, R.E., & Whitebook, M. (2021). Haydee B. Campbell: Expanding Education for Black Children and Opportunities for Black Women. Profiles in Early Education Leadership, No. 1. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. https://cscce.berkeley.edu/haydee-b-campbell.

Suggested Citation

Whitebook, M., & Williams, R.E. (2021). Anna Evans Murray: Visionary Leadership in Public Kindergartens and Teacher Training. Profiles in Early Education Leadership, No. 2. Berkeley, CA: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. https://cscce.berkeley.edu/publications/brief/anna-e-murray/.

Acknowledgements

This paper was developed for the ECHOES™ project, which is generously supported through a grant from the Heising-Simons Foundation.

Special thanks to Claudia Alvarenga for her collaboration and contribution to this project through thought partnership, archival research, and graphic design and data visualization.

Photo Credits

No author (1876). Anna Jane Evans Murray (Photograph) in Evans-Tibbs collection, Anacostia Community Museum Archives, Smithsonian Institution, gift of the Estate of Thurlow E. Tibbs, Jr. Retrieved from https://search.alexanderstreet.com/view/work/bibliographic_entity%7Cbibliographic_details%7C3971377/biographical-sketch-anna-jane-evans-murray#page/1/mode/1/chapter/bibliographic_entity|bibliographic_details|3971377.

No author (1908). PH2003_7063_502-a: Armstrong Manual Training School (Photograph) in Evans-Tibbs collection, Anacostia Community Museum Archives, Smithsonian Institution, gift of the Estate of Thurlow E. Tibbs, Jr. Retrieved from https://sova.si.edu/details/ACMA.06-016#ref263.