Enduring Inequities

ECHOES spotlights elements of the early care and education system that fuel exclusion, exploitation, and injustice in the past and today.

How do inequities echo through time in the ECE system?

Explore photos, quotes, and more from the archives to see how recurring themes across time link with present-day barriers to a more just ECE system.

Poor Pay and Conditions

ECHOES shows how inadequate wages and poor working conditions, a cornerstone of the ECE system, fuel staff turnover and shortages and undermine educator well-being over time.

Insufficient and Unstable Funding

ECHOES traces the burden of insufficient funding and the struggle to finance early care and education as a public good.

Racial Disparities

ECHOES sheds light on how racism has shaped the construction of the ECE system and the experiences of children and families of color as well as teachers and caregivers.

Education Prioritized Over Care

ECHOES explores how federal and state policies and funding have favored services identified as early education over those considered primarily child care.

Women’s Work

Never an Easy Job

Irrational Wage Structure

Many Children, Competing Demands

Nonstop Staffing Crisis

Myths Persist, Teachers Resist

Perpetual Pay Penalties

Racial Disparities Uninterrupted

Essential But Still Invisible

Economic Insecurity Intensifies

New Cornerstones, New Foundation Long Overdue

Worthy Wages – Invest Now!

Depending on Private Dollars and Women’s Resourcefulness

Failure to Thrive, Struggle to Survive

A Century of Campaigning for State and Local Kindergarten Financing

Politics, Policies, and Public Funding

Only Some Benefit, Others Pay a Price

In Case of Emergency, Federal Funds MAY Be Available

From One Emergency to the Next: World War 2

Government Steps Back, While Demand Grows

Don’t Let Them Take Our Day Care

Growing Bigger on Shaky and Uneven Ground

On the Verge of Collapse

What Will It Take?

Deep Roots of Disparity

Immigration and Citizenship Policies Fuel Disparities

Limited and Delayed Access

Unequal From the Start

Black Women’s Visionary Activism

Taking Matters Into Our Own Hands

Elevating Black Women’s Leadership

Seen Only As Workers, Not As Mothers

Race and Federal Early Education Programs

Policies Preserve Inequity

Penalties and Risks

Organizing for Equity

Education and Care: Are They Really Different?

Denigrating Care, Elevating Education

Idealized Norms vs Lived Realities

An Alternative Vision: Integrating Education and Care

(Only Some) Mothers’ Care Is Best

A Different Policy Path for Education

Paths Merge, But Only Momentarily

Child Care Remains a Private Problem to Solve

Policy Choices Maintain the Division Between Child Care and Education

Policy Creates and Maintains Workforce Inequities

What’s in a Name?

From Necessary Evil to Public Good

Women’s Work

Caring for and teaching young children has always been “women’s work,” and the work of women has always been undervalued. Enslaved Black women were forced to take care of other people’s children without pay. After emancipation, Black women were barely paid when hired to do domestic work, which contributed to low pay for caregiving as the norm. Poor pay and working conditions due to racial and gender exploitation are embedded in the foundation of the early care and education system.

“God seems to have made woman peculiarly suited to guide and develop the infant mind, and it seems…very poor policy to pay a man 20 or 22 dollars a month for teaching children the ABCs, when a female could do the work more successfully at one third of the price.” — Littleton Massachusetts School Committee Report, 1849

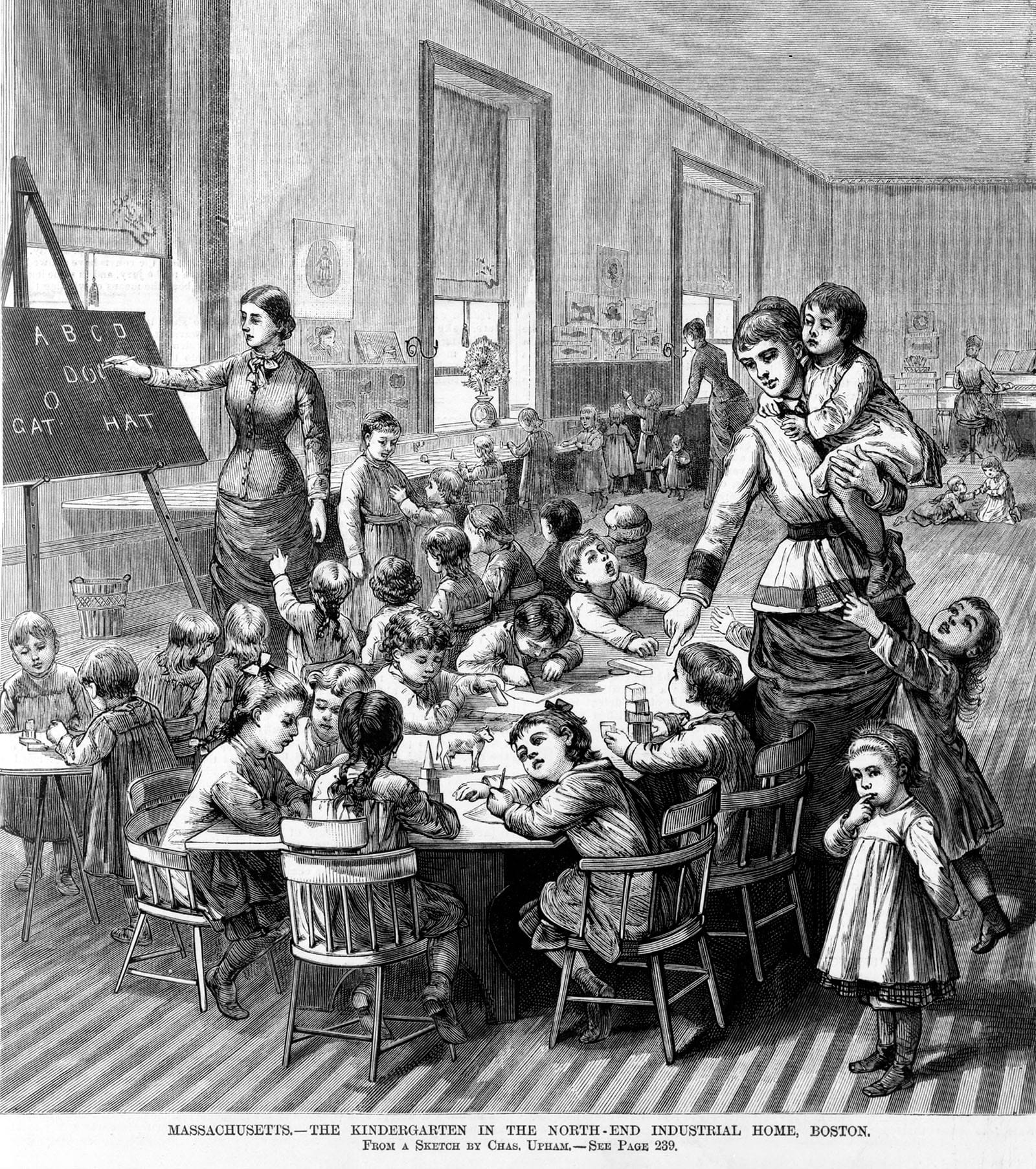

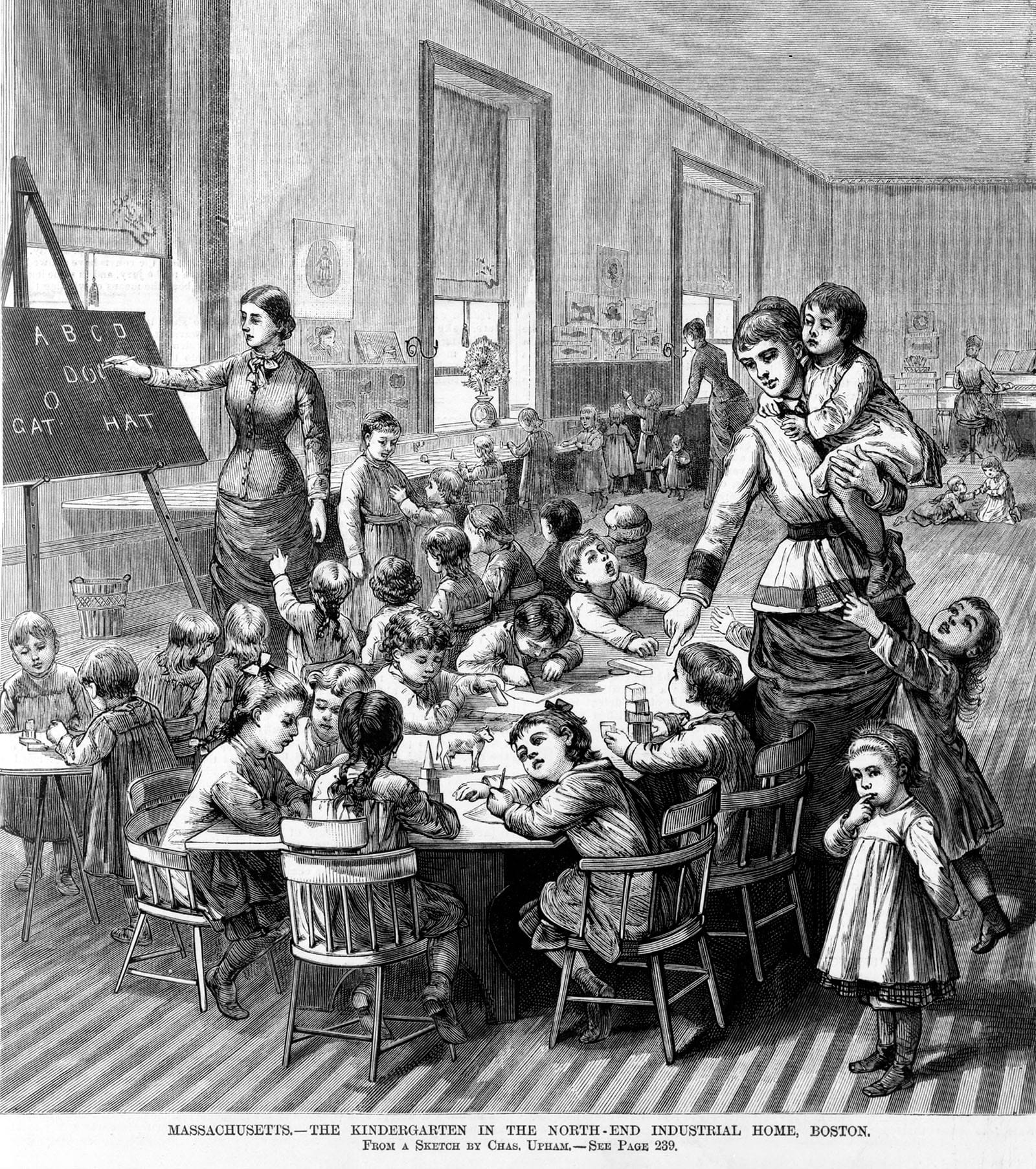

Credit/Source: Photo Sketch from wood carving by Charles Upham, Library of Congress.

Never an Easy Job

Kindergartens, designed for children under six, were a new idea in the 1800s. At the time, it was widely assumed that schooling for young children was unnecessary, teachers of young children needed few skills, and their jobs were “easy.” These beliefs established the rationale for paying early educators less than teachers of older children. Today, those who teach the youngest children continue to be paid the least among all educators.

The first kindergartens often served children between the ages of two and six. Those serving children of industrial workers operated a full day. The demands of long days, working with many children for low pay, was noted by the Brooklyn Free Kindergarten Society, established in 1891.

“The earnestness and efficiency of the kindergartners is out of all proportion to their compensation.” — Brooklyn Free Kindergarten Society, Sixth Annual Report, 1897

Today, those who teach the youngest children continue to be paid the least among all educators. In 2021, early educators experienced poverty at nearly eight times the rate of K-8 teachers.

Read State-by-state analysis shows U.S. child care workforce struggling to survive.

Read our report, The Kindergarten Lessons We Never Learned.

Source: Reprinted with permission in the Child Care Employee Project News, vol. 12, no. 4, Fall, 1993.

Irrational Wage Structure

In every era, program leaders and early educators have voiced regrets about low wages. They understood that poor compensation came at the expense of teacher well-being, staff recruitment and retention, and program quality. In 2020, child care workers remained nearly at the bottom percentile of all occupations ranked by annual pay.

It is a false economy to try to secure nursery matrons and assistants at too low a wage, to employ an inadequate number of workers, or to impose unpleasant conditions of work and living upon them. As soon as there is no longer a fair margin in the working day for period of leisure, for interchange between worker and worker, and between worker and children, loss results in nursery morale and nursery achievement.” — Helen McGee Brenton, A Study of Day Nurseries in Chicago, 1918

“It is hard to be completely present in your teaching when you are constantly worried about other things such as how am I going to make ends meet or if your child is okay because you had to send them to school sick because you couldn’t afford to stay home with them.” — New York Teacher, 20191

- Quote from CSCCE survey of teachers. For more information about the study, see Whitebook, M., Schlieber, M., Hankey, A., Austin, L.J.E., & Philipp, G. (2018). Teachers’ Voices: Work Environment Conditions That Impact Teacher Practice and Program Quality — New York. Berkeley, CA: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved from https://cscce.berkeley.edu/teachers-voices-new-york-2018/.

Credit: Photographer Unknown.

Many Children, Competing Demands

At the Free Kindergarten for Colored Children of New York in 1901, Miss Henrietta W. Moesing and Miss Helena Titus Emerson were responsible for teaching 43 children, slightly more than half of those pictured here.

Today, most early educators still cannot depend on the workplace supports and benefits necessary to their teaching practice and well-being. These supports include paid time off when ill, dependable breaks during the day, and paid time during the work day without child responsibilities to complete professional tasks like planning or reflecting with colleagues.

“Our challenges are that we regularly do not have enough staff and dedicated hours to allocate to thorough lesson planning and preparation. We are in constant survival mode.” — Teacher, Toddlers and three-year olds, Oregon, 20221

“I struggle daily with needing to provide one-on-one support to many students, planning curriculum, working with assistants, following licensing protocol for cleaning, and leading activities with the group.” — Teacher, Four- and five-year olds, Oregon, 20222

- Oregon SEQUAL Study, 2022. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley.

- Oregon SEQUAL Study, 2022. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley.

Source: Boston Area Daycare Workers Union, BADWU RAG, June 1974.

Nonstop Staffing Crisis

Finding and keeping staff has always been a challenge. And it has been even harder when there is demand for workers in other better-paying industries and when some teachers get paid more than others in the same community. The job becomes even more demanding for the staff who remain, which leads to more turnover.

“We cannot expect teachers to go into this work with enthusiasm when they are not receiving the right amount of salary.” — Report of the Association of Day Nurseries of New York for the Year 1919

“Today [the day nursery] is at the mercy of nursery school teachers…who often are not devoted enough to remain for any length of time and move on to something with more prestige. Therefore, the day nursery has a constantly shifting personnel. As one fine director said, ‘We had to learn from experience. Now nobody stays long enough for that.’” — Ethel S. Beer, Working Mothers and the Day Nursery, 1957

Read A Good Sub is Hard to Find, written in 1984.

Credit: Photographer Unknown

Myths Persist, Teachers Resist

Credit: Narrator Rosemarie Vardell, teacher and activist for worthy wages.

Leaving their jobs has not been early educators’ only response to low pay. Teachers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries advocated for higher wages through public funding for kindergarten. In the 1970s and the decades to follow, women who were paid to work with young children in homes, centers, and schools organized for rights, raises, and respect and the public funding required to achieve them.

In a meeting with White House staff in 1995, representatives of the national Worthy Wage Movement made the case for public funding for better compensation, recognizing that parents were already burdened by the cost of child care and could not afford to pay more. Peggy Haack, a family child care provider from Wisconsin, spoke out about the “outrageous myths” from the past that were still being used to justify unworthy wages for the work of early educators:

Myth #1 – Anyone can do this work because training and skills are irrelevant.

Myth #2 – Our income doesn’t support a family, so it’s okay that we only earn $8 an hour.

Read At The Table: Child Care Teachers and Providers Speak Out at the White House from the Worthy Wage newsletter, Rights, Raises, Respect, Spring/Summer, 1996.

Read Peggy Haack’s speech.

Learn more about the organizing and policy strategies of the Compensation Movement.

Credit: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment.

Perpetual Pay Penalties

Those who educate and care for infants, toddlers, and preschool-age children today are among the lowest-paid workers in every state. The burden of underpayment has fallen heaviest on those who work with the youngest children, those whose work is labeled child care vs those called teachers, and those who work in home-based care. Over the centuries, these women have been disproportionately people of color and members of immigrant and other communities that are historically under-resourced.

In 2021, 32 years after the first National Child Care Staffing Study documented the link between low wages of educators and poor program quality, child care workers remain among the lowest-paid occupations in every state.

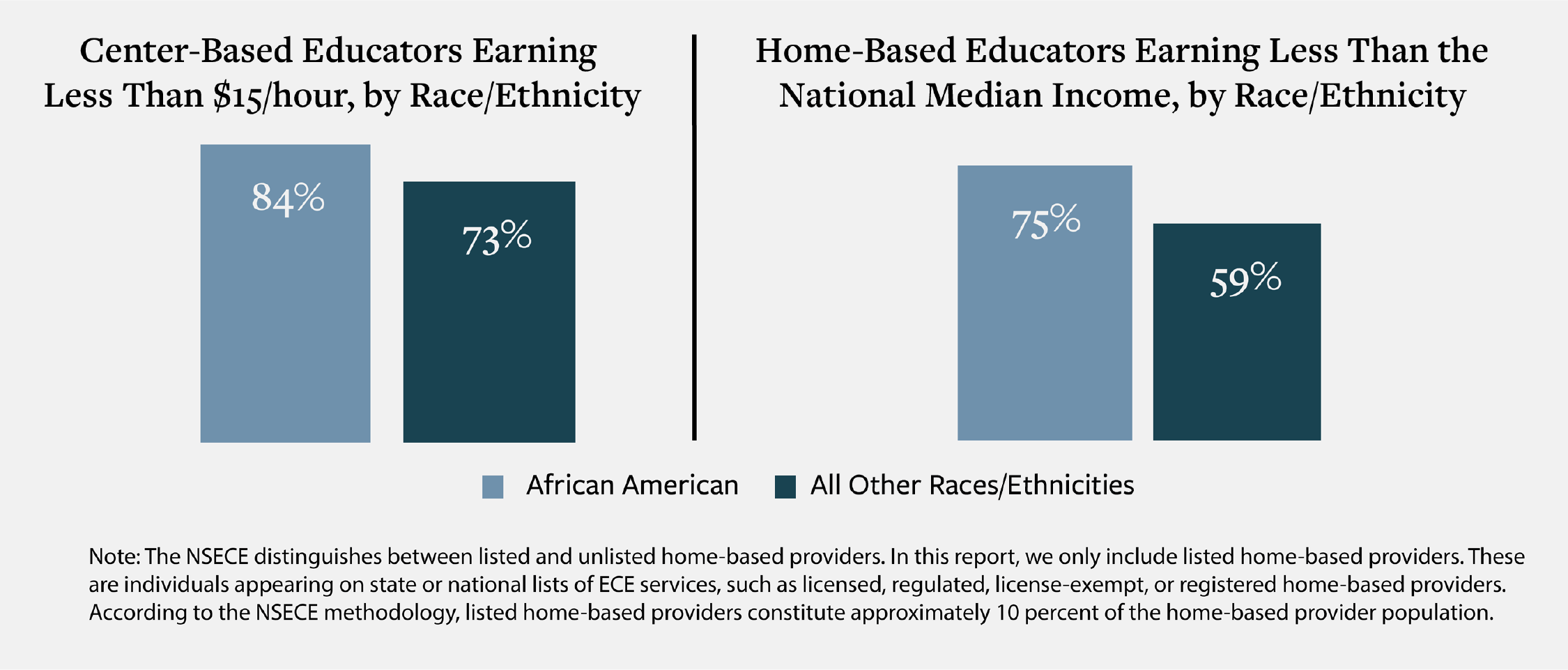

Racial Disparities Uninterrupted

Source: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, Racial Wage Gaps in Early Education Employment, 2019.

There is no singular wage gap within the early education workforce. Gaps vary across multiple factors that are inextricably linked, including funding source, ages of children served, and location. Nonetheless, a discernable pattern emerges in which Black educators in particular are persistently paid less than their peers.

Read Racial Wage Gaps in Early Education, Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, 2019.

Credit: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment

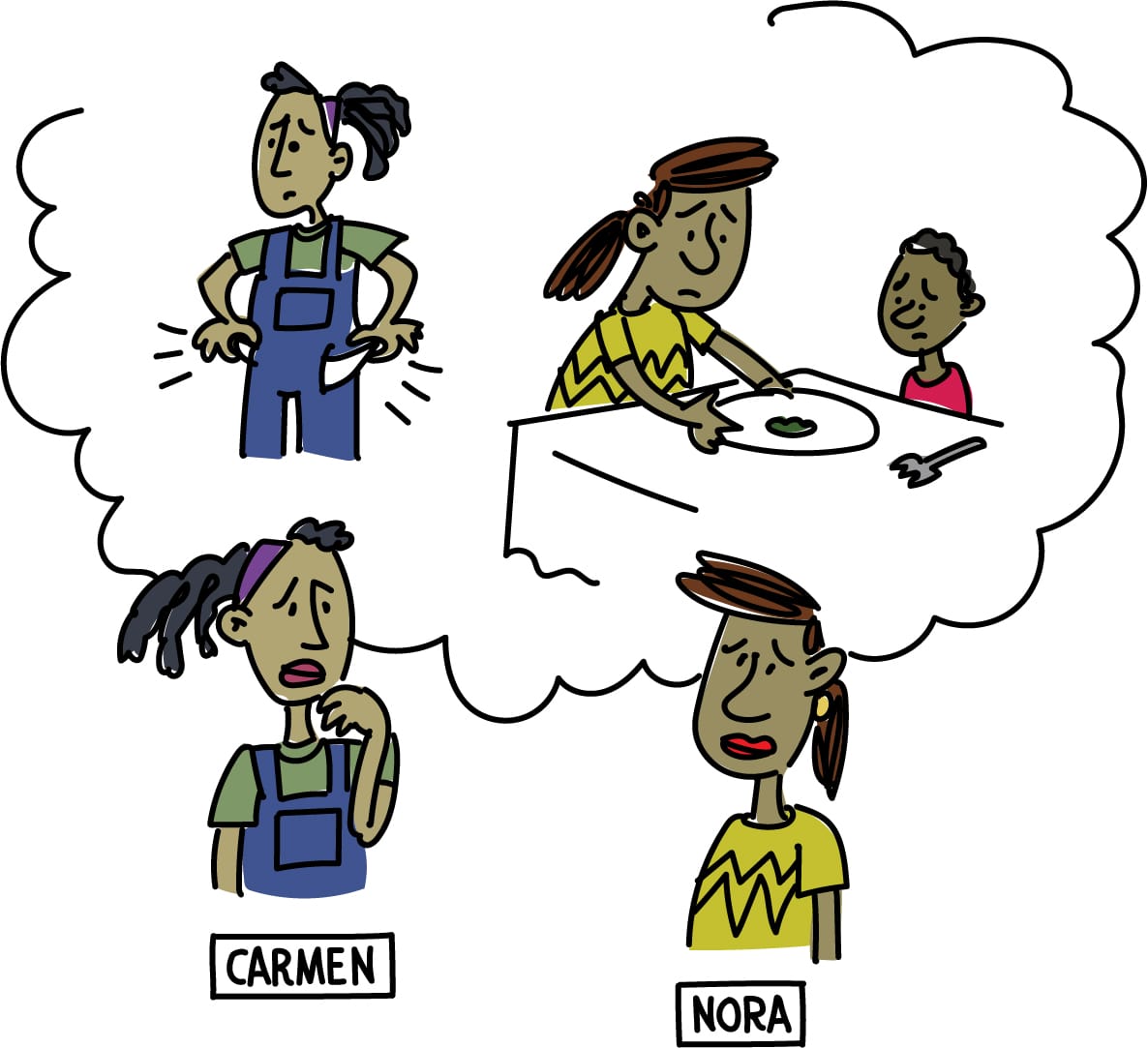

Essential But Still Invisible

Many early educators continued to work with young children throughout the COVID-19 pandemic in their own homes and in centers, risking their health and the health of their families. More than 100,000 early educators lost their jobs because they were laid off or their program closed. Others had their pay reduced, and many family child care providers reported going without pay and working longer hours.

“We put our health at risk five days a week to care for children, and we still don’t get paid enough.” — Center Teacher, Southern California1

“As family child care providers, we are facing unthinkable circumstances and choices. Faced with greater responsibilities than ever. It is like we have entered a battlefield. We are faced with the inner drive to step up and help our community, yet have to find the resources to help keep everyone healthy and safe from this unseen threat. We are faced with the understanding that we start and end each day with the potential risk to our health and that of our family, as well as the families we work with. Doing everything we can to stay afloat, knowing that if we were to fall ill that could have irreversible effects on the future of our business and economic well-being.” — Family Child Care Provider, Southern California 20202

Read Is child care safe when school isn’t? Ask an early educator.

Read The Consequences of Invisibility COVID-19 and the Human Toll on California Early Educators, CSCCE, 2021.

- California Early Care and Education Workforce Study, 2020. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. https://cscce.berkeley.edu/projects/california-early-care-and-education-workforce-study/

- California Early Care and Education Workforce Study, 2020. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. https://cscce.berkeley.edu/projects/california-early-care-and-education-workforce-study/

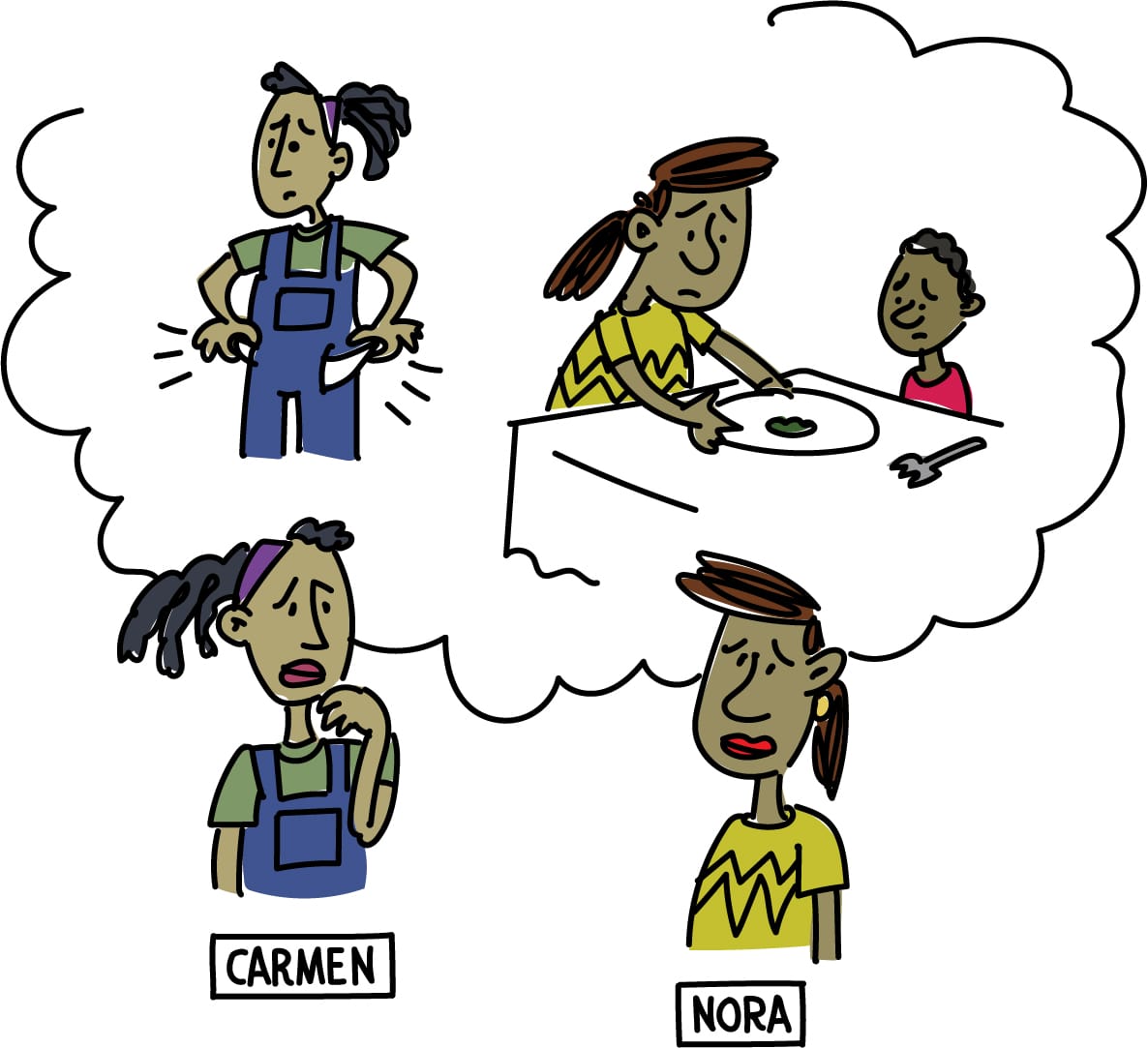

Illustration Credit: Jonathan Lemon. Source: For Our Babies video.

Economic Insecurity Intensifies

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the situation was already grim for early educators. They experienced poverty at rates double those of workers in general, and many early educators reported worrying about their ability to pay for housing, routine health-care costs, and food for their families.

According to the California Early Care and Education Workforce Study, 43 percent of family child care providers were unable to pay themselves at some point during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, and about one third took on credit debt to cover program costs or missed payment for rent or essentials. Family child care providers were about four times more likely than center directors and teachers to experience a decrease in pay.

“We are certainly frontline workers. We are the forgotten ones.… We deserve acknowledgement and better pay, as an industry.”— Center Director, a Black woman in Los Angeles County with forty years of experience in early care and education1

Read “The Forgotten Ones”—The Economic Well-Being of Early Educators During COVID-19.

Read Educator Work Environments Are Children’s Learning Environments: How and Why They Should Be Improved.

- “The Forgotten Ones” The Economic Well-Being of Early Educators During COVID-19.

New Cornerstones, New Foundation Long Overdue

“Ultimately, the economy will reopen, but it can do so in either of two ways: with long-overdue government intervention and support for the well-being of families and providers alike or on the backs of some of the poorest and most marginalized women workers, who will somehow make things work by bearing the burden in every way.”— ECE Teacher, California. 20201

The early care and education system is built on a shaky foundation of racial and gender disparities. The low or foregone wages of early educators subsidize the system to keep prices low for parents and minimize public investments. This abusive structure should have been condemned and replaced long ago. Today as in the past, partial retrofits and cosmetic improvements continue to harm all early educators, especially those who are Black and from immigrant and historically underresourced communities. Just a small bump in pay for some (but not all) early educators will not solve the centuries-long staffing crisis.

In the late 20th century, those caring for and educating children across settings and job roles campaigned for public funding so they could afford to stay and be protected at their jobs and parents could afford services for their children. In the 21st century, others have joined their call. Crumbling before our eyes and crushing those in its wake, the irrational early care and education system is long past due for a new foundation.

Read Increased Compensation for Early Educators.

- Quote from CSCCE survey of teachers. For more information about the study, see Doocy, S., Kim, Y., & Montoya, E. (2020). California Child Care in Crisis: The Escalating Impacts of COVID-19 as California Reopens. Berkeley, CA: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved from https://cscce.berkeley.edu/california-child-care-in-crisis-covid-19/.

Credit: Unknown

Worthy Wages – Invest Now!

Stanza from “Turnover, Turnover,” sung to the tune of “Matchmaker, Matchmaker,” one of many songs written by teacher activists in the 1990s Worthy Wage Campaign.

Explore Worthy Wage Chants & Songs.

Source: A Mother’s Job: The History of Day Care, 1890-1960 by Elizabeth Rose (Oxford University Press, 1999).

Depending on Private Dollars and Women’s Resourcefulness

In the United States, the care and education of young children have almost always been the responsibility of families. Mothers must find the care and cover the cost, which is subsidized by their unpaid labor and the underpayment of other women. Early care and education services have never been a right for all or an obligation of the government. Women with fewer resources of time and money, but often the most pressing need for assistance while they work, shoulder the heaviest burden.

Source: Oakland Public library, African American Museum and Library at Oakland, CA.

Failure to Thrive, Struggle to Survive

Parent fees, subsidized by charitable donations and the underpayment of staff, failed to provide a stable funding base for private kindergartens and day nurseries established by women reformers in the late 1800s.

Reformers dedicated enormous energy and contributed unpaid time enlisting donations of money or goods from supporters through annual memberships and fundraising events. Communities with less wealth, no philanthropic support, and larger demands on scarce resources faced greater challenges. Few of these early care and education services could afford to implement plans to expand.

Hundreds of private day nurseries and kindergartens had to close each year. In 1898 the U.S. Bureau of Education reported that “among the 3,500 private kindergartens sent requests for information, at least 500 were ‘no longer in existence’ and the status of many that failed to respond could not be determined.”

A Century of Campaigning for State and Local Kindergarten Financing

Mothers, teachers, and activists in Black and White women’s organizations sought public dollars to expand and stabilize kindergartens. Their grassroots efforts would grow to become a national crusade to establish half-day kindergartens for all children age three to five in every local public school, supported by tax dollars like education for older children.

- Children’s chances of attending kindergarten, whether public or private, depended on the politics and policies at play where they lived, their age, and their race.

- By 1930, on average, only 15 percent of four- to six-year-olds in the United States attended kindergarten.

- Half-day kindergartens weren’t incorporated in the public school system of every state until the 1990s, and they only served five-year-olds in all but a handful of states.

Today, 150 years after the campaign for the public financing of early education began, three- and four-year-olds are still waiting at the schoolyard gates.

Read our report, The Kindergarten Lessons We Never Learned.

Explore Association for Childhood Education (ACE) Regional and State Kindergarten Histories.

Photo credit: Courtesy of the Anaheim Public Library

Politics, Policies, and Public Funding

Public funding increased access to early education for hundreds of thousands of young children, led to higher salaries for teachers, and lifted the financial burden off families. However, these gains happened far more slowly than activists had hoped, and state school funding policies created barriers.

To open the schoolhouse doors for younger children, activists made do with whatever they could wrangle from local school boards and state legislatures, especially in light of repeated efforts to cut back or eliminate kindergartens.

During periods of economic downturn, kindergartens were particularly at risk of being cut.

- Between 1931 and 1933, 19.8% of U.S. cities reduced or cut public kindergartens more than music, art or physical education. (Beatty, 1995, p. 172).

- 17% fewer four to six-year-olds attended public kindergarten in 1934 than in 1930. The numbers would continue to fall until the end of the decade and did not rebound until the mid-1940s.

Read our report, The Kindergarten Lessons We Never Learned.

Credit: Photo by Masako Hirata, Courtesy of the San Bernardino Public Library.

Only Some Benefit, Others Pay a Price

Public funding for kindergarten prioritized spending on early education for children age five, leaving child care and early education services for younger children as a private commodity.

These priorities would shape future public financing for early care and education, intensifying the cost burden on families of younger children and families in need of child care, reinforcing the undervaluing and underpayment of staff, and exacerbating turnover in privately funded programs.

The increasing demand of well-trained kindergartners in our public schools has made the path of the Committee difficult at times. We have been obliged to accept the resignations of teachers during the school year, who, with good reason, desired advancement and increased salary. While we are interested in the welfare of all kindergartens, we were loath to see our particular ones suffer because of these changes. — Brooklyn Free Kindergarten Society Annual Report, 1902, p. 23

Credit: Russell Lee. Source: Library of Congress.

In Case of Emergency, Federal Funds MAY Be Available

During the Great Depression, the federal government committed funds to early care and education for the first time. In 1933, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) established the Emergency Nursery School Program to provide educational guidance, nutrition, and health care for children age three to five while their families were on relief, in conjunction with a jobs program for unemployed teachers and other workers.

Services were free to families, and teachers’ salaries were paid by federal funds in the nearly 2,000 emergency nursery schools set up in public schools throughout the United States.

The Emergency Nursery School Program was designed as a crisis intervention and ended in 1942, when jobs became plentiful again.

Because the 50,000 to 70,000 children served in WPA emergency nursery schools each year represented only a small fraction of eligible children, two lesser-known federal programs were established for young children during the Depression.

- 41 nursery school programs were operated by the Department of Agriculture and provided child care and other services for children of migrant workers.

- 2,714 play centers for young children were established in 1936 and run under the auspices of Community Recreation Programs, but did not offer educational guidance or address children’s health or nutritional needs.

Source: New York Times.

From One Emergency to the Next: World War 2

The 1940 Lanham Act Child Care Program addressed the needs of mothers with young children as women entered the labor force in greater numbers during the war. Half of the WPA nursery schools were adapted to become part of the Lanham Act Child Care Program, which was also designed to last only for the duration of the emergency.

The Lanham Act Child Care Program was neither universal, fully funded, nor free.

Despite its limitations, the Lanham Act Childcare program integrated child care and early education during WW2. It served children regardless of their family income and briefly disrupted the division between child care and education, as well as the association between child care and welfare.

Like the WPA emergency nursery schools, the wartime child care centers were intended for a specific population and underfunded. They met the needs of only a fraction of the mothers who were eligible, but only if they lived in war-impacted communities. Infants and toddlers were not served (with few exceptions), parents were required to pay a fee, and communities were obligated to fund a portion of center costs.

As a result of these stringent requirements, most working mothers were excluded and had to rely on more expensive private programs, babysitters, neighbors, or older siblings, just as many had been doing before the war.

Credit: San Francisco Chronicle. Source: Bancroft Library, University of California

Government Steps Back, While Demand Grows

By the early 1950s, after a brief decline, mothers’ labor force participation matched its WW2 peak and kept growing.

The demand for child care continued when federal funding for educational child care programs abruptly ended in 1946. When nationwide objections from working mothers and teachers failed to reverse the government’s decision, only activists in California, Massachusetts, and Washington succeeded in securing state money to replace some of the federal funding.

The movement for public financing rallied against federal inaction, and activism in the 1960s culminated with Congress passing the bipartisan Comprehensive Child Development Act of 1971 to establish a national system of comprehensive child development and day care.

But President Nixon vetoed the legislation, saying it was characterized by “fiscal irresponsibility, administrative unworkability, and family‐weakening implications.” Instead, he signed the 1971 Revenue Act, with a provision for tax deductions to offset a minor portion of costs for child care purchased in the private market, which helped more-affluent families.

Read the New York Times Account of President Nixon’s veto of the Comprehensive Child Development Act, December, 1971.

Don’t Let Them Take Our Day Care

In the decades following the 1971 veto of the Comprehensive Child Care and Development Act, government funding has been constrained, while a reliance on the private market has been the dominant strategy to provide early care and education services.

Starting in the late 1970s and through the 1990s, teachers, providers, and parents acted together and separately to protest cutbacks. Simultaneously, they sought increased funding in order to:

- Increase access for more children;

- Lower parents’ co-payments;

- Remove onerous eligibility requirements for child care subsidies; and

- Increase compensation for early educators.

Early victories in Massachusetts and New York in the 1970s and 1980s inspired other activists to push for bolder federal policy reforms. Many of these advocates were among the first to call out the under-resourced early care and education system’s perpetuation of gender and racial exploitation and its function as a pathway to poverty for those using and providing ECE services.

Read the Boston Area Daycare Workers United (BADWU) pamphlet year Don’t Let Them Take Our Day Care.

Read “Fair Rates + Fair Wages” = $25 Million Victory in Massachusetts.

Growing Bigger on Shaky and Uneven Ground

Public funding for child care and early education has increased over the past four decades, but the vast majority of children under age five in the United States remain ineligible for any publicly funded early care and education services.

In a market-based system, children’s access to services, the quality of these services, and the compensation and working conditions of their teachers and providers depends on their families’ private resources.

The Department of Defense program, which is restricted to the children of military personnel, stands alone as the only federal program to integrate care and education and guarantee services for all children across every income level.

The many other federal early care and childhood programs, such as Head Start or subsidized child care, restrict eligibility to children living in families with very low incomes.

Watch: Why Do Parents Spend So Much On Child Care, Yet Early Childhood Educators Earn So Little?

Credit: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment.

On the Verge of Collapse

The early care and education system was nearing a total breakdown in 2019. It was just a matter of when. The signs were everywhere:

- An unrelenting staffing shortage following decades of unlivable wages and increasingly demanding work environments;

- Crushing (and still rising) costs for families desperate for services; and

- Corporate-operated child care programs stepping up to profit as other types of center-based programs as well as small family child care programs owned by women and people of color closed because they could no longer afford to stay open.

A few policymakers had already introduced legislation to increase federal investment and reform the system.

And then the COVID-19 pandemic hit, and on its heels, the predicted breakdown. But nobody had foreseen the anxiety, pain, and suffering for those who lost their livelihood or those who continued to work, risking their lives and health and the lives and health of their loved ones.

As during previous national crises, the federal government allocated temporary relief funding for child care in 2020 and 2021. Yet, early care and education continues to recover more slowly than other sectors. Failure to recover is entirely likely if relief funding ends without immediate plans for future investment.

What Will It Take?

- Only one in seven children eligible for federal child care assistance received it in 2018 (National Women’s Law Center, 2022).

- Head Start serves less than 50% of income-eligible children.

- Early Head Start serves less than 10% of income-eligible infants and toddlers (National Head Start Association, 2021).

In 2020, the Economic Policy Institute estimated that it would cost in the range of $337 to $495 billion annually to pay for an enhanced early care and education system that would serve between 11.5 and 16 million children, raise educator pay, and reduce costs to families.

More money alone will not mend the ECE system. Established on a foundation of racial, gender, and class inequities that should have been dismantled long ago, early care and education has been maintained on the backs of millions of women who provide these services for poverty-level wages. The necessary investment requires a new foundation with a commitment to equity and racial justice and the integration of early education and care as its cornerstones.

It will take a bold national movement to achieve these far-reaching changes.

Read Working Toward Early Childhood Education Equity – Center for the Study of Child Care Employment.

Credit: Photo by Nellie T. McGraw Hedgpeth, Courtesy of UC Berkeley, Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology.

Deep Roots of Disparity

The political and economic system of the United States rests on a foundation of racial and gender exploitation and harm as a result of the colonization of Indigenous lands and the enslavement of Black people. The U.S. economy today still depends on racial and gender disparities stemming from this history.

Black women’s unpaid and underpaid labor is the cornerstone of the early care and education system. From when they were enslaved and up to the present, Black women have cared for other people’s children while their own needs for child care and the education of their children have been denied, delayed, and under-resourced.

Kindergartens for young Native American children were a component of the brutal government-sanctioned campaign. Beginning in the 1890s, the federal government funded more than 40 kindergartens1 often operated by missionaries and churches. The kindergartens were operated both on reservations and in boarding schools, meaning that some children as young as four were physically separated from their families and communities and sent to boarding schools. Young children were stripped of their tribal language, dress, and customs and endured physical and psychological violence, in some cases resulting in death, for resisting speaking English and adopting White Christian practices and norms, such as individualism. The resulting trauma of these experiences are carried across families and entire communities and tribes today.

Read California’s History of Discrimination and Exclusion Haunts Early Care and Education Today

Read Healing Voices Volume 1: A Primer on American Indian and Alaska Native Boarding Schools in the U.S.

Read Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report

- The history of Native American kindergartens has been mostly erased from the history of early care and education. The records of Native American kindergartens, as in the case for boarding and reservation schools, are still being discovered in public archives and private collections across the country. As a result many questions remain unanswered about the federally funded kindergartens, including the ages of children attending, the number of children removed from their families, and at what age they were removed, and the variation among them.

Credit: Courtesy Hiroshi Shimizu. Source: Densho.

Immigration and Citizenship Policies Fuel Disparities

Racial inequities have been sanctioned by public policies, maintained by discriminatory practices, and bolstered by harmful stereotypes and beliefs. These policies have shaped access to services and educational experiences for children from Black, Indigenous, Hispanic/Latinx, Asian American, and other historically oppressed communities.

Racist immigration and citizenship laws, nativist exclusion, and deportation policies imposed throughout U.S. history and today have subjected many children to traumatic and damaging separations from their homes, families, and communities and caused severe financial hardship for their families. These policies have limited families’ ability to access publicly funded early childhood services or afford other types of formal care and education. Many families may choose other family members, friends, or neighbors to care for and educate their children for any number of reasons, including shared language and culture, hours, and affordability, but for some families, this informal care is the only option available.

Read US immigration policy: A classic, unappreciated example of structural racism

Read The Importance of Family, Friend, and Neighbor Care for Immigrant and Dual Language Learner Families

Read What “Back to School” Looked Like in World War II Concentration Camps

Credit: 1900 Paris Exposition from Du Bois (1909).

Limited and Delayed Access

In the early 20th century, 90 percent of the Black population resided in the southern states, where neither public nor private kindergartens had been established in most communities. Black children did not have access to public kindergarten in cities in other regions of the country and also had less access to “free” or “charity” private kindergartens that mostly served White European immigrant families. Black women stepped in to provide services.

The most elaborate effort at systematic free kindergartens is that of the Gate City Free Kindergarten Association of Atlanta, Georgia. Some years ago, some colored people of the city started a free kindergarten association. It ran a kindergarten for two years and then getting into financial difficulties […] the colored women rallied again, and the result has been five free kindergartens here in operation; four of them since 1905 and the fifth started last year. No aid is received from the State, although the white kindergartens receive such help. — Du Bois, 1909, p. 1261

Despite many efforts, there was a lack of kindergarten opportunities for Black children, even for families with private funds. In a survey prepared for the 1931 White House Conference on Child Health Protection, racial disparities in access to private kindergartens were documented nationwide. Only 8.2 percent of Black children under age five attended kindergarten, as compared to almost 30 percent of White children the same age (Anderson, 1936, pp. 266, 332).2

- Some Efforts of American Negroes for Their Own Social Betterment Report of an Investigation Under the Direction of Atlanta University; Together With the Proceedings of the Third Conference for the Study of the Negro Problems, Held at Atlanta University, May 25-26, 1898 by W. E. Burghardt Du Bois

- Anderson, J. E. (1936). The Young Child in the Home: A Survey of Three Thousand American Families, Report of the Committee on the Infant and Preschool Child. D. Appleton-Century Company.

Credit: G. N. Grisham. Source: Southern Workman, 1902 v.XXX, no. 11.

Unequal From the Start

St. Louis was the first U.S. city to establish a public kindergarten in 1872. There were already more than 50 White kindergarten classes when the first Black kindergarten was opened in 1879. The second Black kindergarten was established 10 years later in 1889. It took nearly 50 years to establish 31 Black kindergartens by 1938.

Although public-school kindergartens offered Black teachers better pay than private kindergartens or day nurseries, their pay rates were set lower than the rates for White teachers performing the same work, with very few exceptions.

Public kindergarten opportunities for most Black children were delayed or outright denied and were almost always segregated and more poorly funded.

Participation rates in public kindergarten continued to lag for Black children at the end of the 20th century. During the COVID-19 pandemic, declines in kindergarten enrollment were greatest in historically under-resourced communities with large populations of Black, Latinx/Hispanic, and other children of color.

Read our report The Kindergarten Lessons We Never Learned.

Credit: Courtesy of the Los Angeles Public Library.

Black Women’s Visionary Activism

After the end of enslavement, most Black women had to work for pay outside their homes and needed child care in their communities. Black club women embraced expanding child care and early education as a key strategy to build racial and economic justice after Reconstruction. They understood the economic necessity of Black mothers’ employment as well as their aspirations for their children to be educated. The National Association of Colored Women, a federation of Black Women’s Clubs, provided institutional infrastructure and financial resources for starting free or low-cost private Black day nurseries and kindergartens and advocated to secure public funding for kindergarten.

Activists in Black Women’s Clubs worked locally to correct the racial disparities in kindergarten access and to create culturally appropriate experiences for Black children age three to six, while facing additional challenges to secure funding and establish training opportunities for prospective Black kindergarten teachers.

Credit: Griffin, M. K. (1906). Source: The Colored American Magazine, Courtesy Charities and the Commons.

Taking Matters Into Our Own Hands

Black mothers often relied on neighbors, relatives, or their older children to care for their youngest, but since these caregivers also had to work, other options were required. Frequently excluded from nurseries established for White children, Black women set up day nurseries in their own communities that did not subject working mothers to demeaning “moral tests,” which were common in those services established by White day nursery leaders.

Relying primarily on community donations and parent fees, Black day nurseries struggled to survive, particularly in times of economic distress or when they had to relocate due to rising rents (often due to White families moving into the neighborhoods).

The Hope Day Nursery, one of the few day nurseries serving Black families in New York City in the early 1900s, was forced to relocate during WW1. It survived longer than most Black day nurseries but only for about a decade after the move.

The Hope Day nursery, like all other charitable institutions, has felt keenly the brunt of the almost world-wide war. It has therefore been, only by the most careful management, that the Board, with the assistance of our ever-frugal Matron, managed to keep our doors open. — Hope Day Nursery Annual Report, 1918, p. 5

Credit: State Historical Society of Missouri, Research Center, St. Louis, Missouri.

Elevating Black Women’s Leadership

Histories of early education have focused on White leaders and thinkers like Elizabeth Peabody and Frederick Froebel, ignoring the activism, pedagogical contributions, and leadership of Black women as well as those from other under-resourced communities.

Haydee B. Campbell, Anna E. Murray, and Josephine S. Yates were three visionary Black leaders motivated by a belief in the power of kindergarten education to improve Black children’s lives as part of their commitment to “racial uplift.”

Haydee B. Campbell was the first Superintendent of Black Kindergartens in St. Louis, Missouri, in the late 1800s in the groundbreaking, yet segregated public kindergartens in that city. Her responsibilities included training Black kindergarten teachers, assistants, and volunteers. She went on to head the National Association of Colored Women’s Kindergarten Department, where she created national training programs.

Anna E. Murray successfully advocated for public kindergartens for Black children and training programs for Black teachers in Washington, D.C. After she secured public funding for kindergarten in Washington, D.C., Murray pursued her vision for expanding early education in the southern states, laying the groundwork for scaling training programs for Black women in the South and urging the federal government to provide funding.

Josephine S. Yates was an educator, writer, and Black Women’s Club leader. As the second president of the National Association of Colored Women (NACW), she promoted a multifaceted advocacy agenda that included providing resources to assist local Black Women’s Clubs in establishing kindergartens and day nurseries. She also interpreted Froebel’s theories with an emphasis on how teachers could apply them to affirm young Black children’s strengths.

Credit: Dayton Daily News, March 8, 1920.

Seen Only As Workers, Not As Mothers

Use of Black women’s labor to provide care for White children, while their own needs as mothers are denied, goes back to the days of slavery. Black mothers employed as domestic workers struggled to find care for their own children even as they looked after their employers’ children. At the same time, domestic workers were also expected to clean, cook, wash clothes, and perform countless other duties, while enduring verbal, physical, and sexual abuse from employers.

Working hours were unpredictable for domestic workers and often extended overnight, resulting in extended separation from their children, which intensified the difficulties domestic workers faced in finding and paying for child care. Exploitative pay and working conditions led Black domestic workers to organize for their rights and reform racist and misogynist state and federal labor laws in the 1930s and 1940s.

In the last quarter of the 20th century, the never-ending demand for cheap labor in our capitalist economy, alongside reductions in public spending, led to policies explicitly designed to undervalue Black women and other women of color as mothers. Black mothers receiving welfare payments to care for their children were denigrated with racist stereotypes, in stark contrast to the idealization of stay-at-home mothers, which led to state widows’ pensions and the federal Aid to Dependent Children program primarily used by White mothers.

Time limits and work rules were imposed on recipients of welfare. Many mothers on welfare faced new challenges in finding care for their own children when they were steered into low-paying child care jobs to meet the growing demand from White and middle-class mothers. Black activists organized the Welfare Rights Movement.

In response to new education and employment opportunities won through the civil rights movement, many Black women have left domestic work entirely. Today immigrant women from Latin America, the Caribbean, and Asia comprise the domestic workforce, leading to new struggles for changes in immigration policies that undermine their labor protections.

The domestic worker and many other movements continue the fight for labor and economic justice.

Credit: Courtesy of the National Archives.

Race and Federal Early Education Programs

Designed during the Great Depression for families in under-resourced communities, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) Emergency Nursery Schools Program was the first federally funded and operated early education program and one of the first federal programs since Reconstruction for which Black children and adults were eligible to participate. The federal government intentionally established some nursery schools for children living in under-served communities with large populations of Black, Latinx/Hispanic, and White children whose parents were often migrant workers. The aim was to boost early education in communities with low levels of kindergarten participation in southern and western states. Although integrated nursery schools were encouraged, in practice, most were segregated. Black and Latinx/Hispanic children constituted 15 percent of the population enrolled in the program, reflecting their 1930s national population distributions (Arboleda, 2019; Burlbaw, 2009).1

Head Start (est. in 1965), the most well-known and enduring federal early education program, was also designed for children living in under-resourced communities. Both the WPA Emergency Nursery School and Head Start increased ECE services for children from Black, Indigenous, and other historically underserved communities and created early childhood training and career opportunities for many adults in their lives.

While Head Start has evolved over time, thanks to the activism of community members and the efforts of staff and parents to provide strength-based and culturally affirming services, the program’s roots stem from racist and classist beliefs about the children and families it was designed to serve. Head Start was founded on the notion that correcting parental behavior and intervening in under-resourced children’s lives would change their trajectory. This belief was reflected in remarks from one of Head Start’s founders, Robert Cooke, who commented on “the nearly inevitable sequence of poor parenting which leads to children with social and intellectual deficits, which in turn leads to poor school performance, joblessness, and poverty”.2

Though there is no explicit discourse today of Head Start as a compensatory program for children and their families, many suggest that the pretext of today’s educational reform movement to which Head Start is increasingly linked and its language of closing the achievement gap and targeting those “left behind” (Dudley-Marling, 2007) is ostensibly a strategy born of a deficit perspective on under-resourced children of color and their families (Dudley-Marling, 2007; Hollins, 2008).

- Arboleda, M Q.(2019) Educating Young Children in WPA Nurseries: Federally Funded Early Childhood Education from 1933-1943. Routledge. Burlbaw, L. M. (2009). An Early Start: WPA Emergency Nursery Schools in Texas, 1934-1943. American Educational History Journal, 36(1-2), p. 269-298.

- Who cares for our children?: The child care crisis in the other America. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Credit: T. J. O’Halloran, Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Policies Preserve Inequity

Federal policies have the potential to disrupt and eliminate racial disparities in the early care and education system. Indeed, some policies have reduced these inequities over the years. But federal early childhood policy, which depends on primarily market-based private early care and education, has created and continues to reinforce racial disparities through the egregious underpayment of early educators and the impoverishment of mothers who must pay for services in order to be employed.

Chronic underfunding of federal child care subsidies and early education programs designed for children from historically oppressed and under-resourced communities ends up excluding them and causing economic hardship.

- Nationally, Head Start serves only 54% of eligible Black children and 38% of eligible Hispanic/Latinx children (Institute for Child Youth and Family Policy, Brandeis University, 2020).

- Head Start still operates part-day and on a school-year calendar, leaving the equally important child care needs of families unaddressed. Head Start, and more recently Early Head Start for infants and toddlers, has never been sufficiently funded to serve all eligible children.

- Due to underfunding, six out of seven eligible children do not receive child care subsidies (National Women’s Law Center, 2022).

Women of color comprise the majority of home-based early educators, and nearly half of those working in centers. And they are the most harmed by differences in funding across settings and programs defined as care or education. Furthermore, while federal policy implicitly and explicitly supports informal license-exempt care, it offers little by way of support or opportunities to improve the livelihood of the many immigrants and other women of color who provide these services to their communities.

Meanwhile all these underpaid women who subsidize the system through their low wages are crushed by the cost of child care, just like other families. The Economic Policy Institute estimates that the median child care worker would have to pay between one third and two thirds of her earnings for infant care for one child.

Read The Importance of Family, Friend, and Neighbor Care for Immigrant and Dual Language Learner Families

Source/Credit: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment.

Penalties and Risks

Overworked and under-compensated, early care and education providers are among the lowest-paid workers in the labor market. The early care and education sector is composed almost exclusively of women, 40 percent of whom are people of color, who are paid lower wages than their White counterparts. Early educators of color are more likely to teach the youngest children, which pays less, and they are less likely to be lead teachers or administrative leaders, positions that pay more.

Listen: Lea Austin discusses the racial wage gaps in early education.

The COVID-19 pandemic increased the harmful impact of racial inequities. A study reported on the Chalkbeat website, found that among more than 1 million child care workers in the United States, 405 died from COVID-19 in 2020. “That translates to 38 deaths for every 100,000 child care workers — a higher rate than workers overall, and one similar to others in ‘essential’ industries where in-person work was common” (Barnum, 2022).

Credit: Maniscalco, J. Source: LaborPress.

Organizing for Equity

Throughout the history of early care and education, activists built movements that worked to narrow the gap between the system as it exists and their vision. In this vision, all teachers are well paid and respected; all children have a right to well-resourced and culturally affirming environments, regardless of their age, race, where they live, or their parents financial resources or work lives.

Activists have been central to keeping rights, raises, and respect on the table. Without them, we would not be talking about issues like pay parity or funding ECE as a public good.

A bigger and better-funded system alone will not end racial disparities. We need policies to end the pay penalties that mean teachers of younger children earn less than those who teach older children. We need policies that will disrupt the racial and gender inequities woven into the ECE system. We need a new foundation with a commitment to equity and racial justice and the integration of early education and care as its cornerstones.

The lives of the early activists guide and inspire us!

Credit: J. Vachon, U.S. Farm Security Administration, Office of War Information Photograph Collection, Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Education and Care: Are They Really Different?

Kindergartens and day nurseries emerged in the late 1800s to address concerns about the safety and socialization of young children at a time when most believed a mother’s place was in the home guiding her young children.

At first, kindergartens and day nurseries were fairly indistinguishable with respect to funding and goals. Both aimed to preserve the family and transform the character of children, particularly those living in under-resourced communities. Most kindergartens welcomed three- to six-year-olds but only for a half day during the school year, although some adjusted their schedules for children whose mothers were employed. Day nurseries (which often included kindergarten programs) were open year-round for longer hours, providing services for infants and toddlers and after school for older children to meet the needs of employed mothers.

A division between the two services soon arose. Day nurseries were perceived as undermining the home by enabling mothers to work when most people believed that they should remain at home caring for their children. In contrast, kindergarten’s educational programs for children and mothers were viewed as enhancing the home and “proper” motherhood. Although many day nurseries also offered educational programs for mothers and children, they were viewed as only providing custodial care.

Credit: New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Denigrating Care, Elevating Education

Most of the day nursery movement leaders were ambivalent champions for their cause. They shared the dominant belief about a mother’s place being in the home, although the lived experiences of the mothers they served did not conform to this idealized norm.

Even the Progressive Era reformer Jane Addams, who founded the Hull House Settlement in Chicago in 1889 with a day nursery and a kindergarten, harbored biased concerns:

The day nursery is a “double-edged implement” for doing good which may also do a little harm. It may even be called a necessary evil. — Charities, 1905

“But it must be distinctly understood that the help is only temporary, otherwise the Nursery becomes crutch; and they continue to walk lame as long as they can use it.” — Unnamed Day Nursery Leader speaking at the 1892 National Conference of Charities and Corrections, 1892 Conference Proceeding, p. 425

Many activists who sought public funding for kindergartens quickly realized that any association with day nurseries serving the children of working mothers damaged the cause of early education:

[Kindergartens and day nurseries] have frequently been established together, both serving a philanthropic purpose. In consequence the kindergarten is regarded by thousands as being little if anything more than an advanced form of the day nursery, whose purpose is served if the children are kept clean, happy, and off the streets. — Vandewalker, 1908

Read our report, The Kindergarten Lessons We Never Learned.

Credit: Department of Labor, Women’s Bureau, Courtesy of the National Archives, College Park, Maryland.

Idealized Norms vs Lived Realities

Notions of the “proper” family, with a single male breadwinner and stay-at-home mother, directly clashed with the economic realities of historically under-resourced communities. This dominant ideal was impossible to achieve without access to livable wages and stable employment, largely the result of racial and ethnic discrimination and labor exploitation.

Working-class, Black, and immigrant women faced the need for child care first: they entered the paid labor force decades before middle-class White women. In 1920, for example, Black women (43.7%) were more than twice as likely as White women born in the United states (20%) and White women born abroad (18.8%) to be engaged in gainful employment. Racial, nativist, and class prejudices toward the users of early day nurseries contributed to the unfavorable view of child care, underlying some of the resistance to establishing and funding services.

By the late 1920s, day nurseries constituted a very small portion of child care used by working mothers in most cities. A 1927 New York Urban League Study in Harlem found that most child care was provided by friends and relatives, many of whom were paid little if anything because the mothers, who covered the cost themselves, were underpaid for their labor. A century later, many families continue to rely heavily on friends and relatives for child care due to issues of cost and limited availability of more formal arrangements.

Credit: Tampapix, http://www.tampapix.com/armwood.htm.

An Alternative Vision: Integrating Education and Care

Black club women and other Black community leaders in the late 19th and early 20th centuries understood that the integration of care and education was vital to working mothers’ aspirations for their children and their protection in a society that routinely ignored their needs. Resisting the ever-wider divide between day nurseries and kindergartens that developed in the first half of the 20th century, Black activists established services like the Helping Hand Day Nursery and Kindergarten in Tampa, Florida, in 1924. Reflecting the needs of families in their communities, Helping Hand Day Nursery provided essential services to the community for many decades.

Unfortunately, despite the efforts of local Black activists like those in Tampa, most Black children had only limited access to segregated kindergartens and private day nurseries in most cities throughout the United States.

The Tampa Urban League’s Helping Hand Day Nursery and Kindergarten, 1951.

Credit: Tampapix.

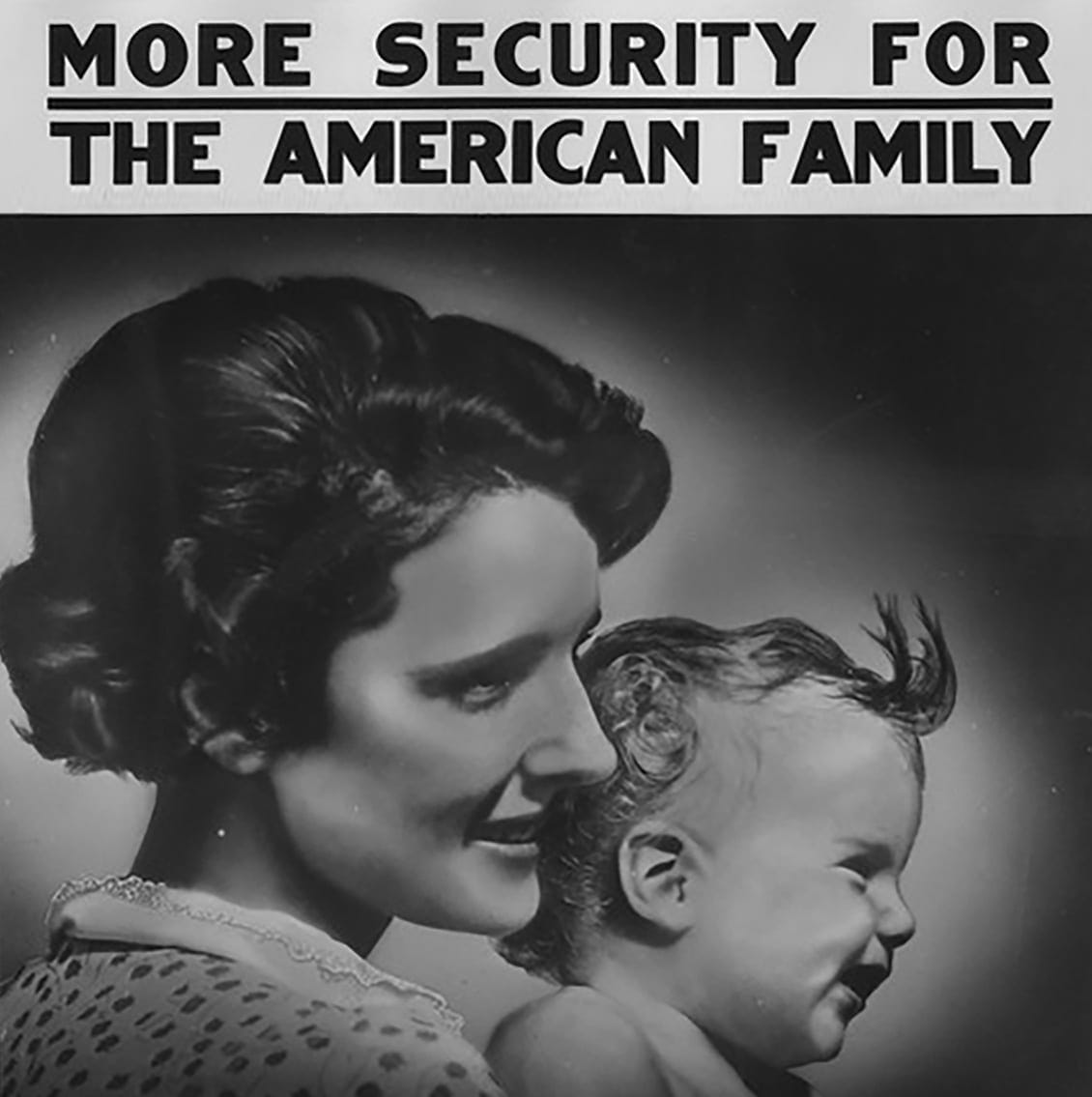

(Only Some) Mothers’ Care Is Best

Imagine if government leaders had pursued the vision of Black leaders in the early 20th century and our current system reflected their integrated vision of care and education. To the contrary, federal and state leaders upheld gendered expectations of mothers at home with the youngest children and preferred investing public funds for mothers’ pensions rather than in child care programs.

As one of its first actions, the federal Children’s Bureau (est. in 1912), played a key role in promoting state-supported mothers’ pensions throughout the country. Pensions were established in all but two states between 1911 and 1933. They were almost exclusively restricted to “needy” White mothers.1 Support was for those “deprived of the support of the normal breadwinner through death, absence from the home, or physical or mental disability.”2

These racist and restrictive eligibility criteria reinforced the idea that only some mothers were judged worthy of assistance, putting the lie to the assertion that all mothers’ care was best.

And yet, during the Great Depression, these discriminatory practices and assertions would be codified into federal law through the Aid to Dependent Children (ADC, later renamed Aid to Families with Dependent Children, AFDC) in the Social Security Act (1933). Unabashed and disingenuous claims promised that ADC would ensure the “loving care” of mothers, which was the “best security” for children. In reality, ADC was the first of many federal policies adopting policies that deny the realities of many mothers of young children, while claiming to address their needs.

This 1940 poster reminded the public about the Aid to Dependent Children program established under the Social Security Act of 1935.

Credit: Social Security Administration History Archives.

- Fox, C. (2013). Three Worlds of Relief: Race, Immigration, and the American Welfare State from the Progressive Era to the New Deal, Princeton University Press.

- Social Security in America, Chapter VIII, Aid to Dependent Children https://www.ssa.gov/history/reports/ces/cesbookc13.html

Credit: A. Rothstein, Farm Security Administration, Office of War Information Photograph Collection, Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

A Different Policy Path for Education

In the first decades of the 20th century, federal government policies disparaged day nurseries and disregarded the needs of working mothers, while enthusiastically endorsing efforts in states and local communities to expand and incorporate kindergartens for children four to six years of age in public schools. Although the federal government did not provide funding for state and local kindergartens, it disseminated promotional materials for the public, developed training and other resources for kindergarten teachers, and published biennial reports on progress throughout the country.

During the Great Depression, however, the federal government designed and funded an early education program for three- to five-year-old children living in families on relief through the Works Progress Administration (WPA): the Emergency Nursery School (ENS) Program (1934-1943).

As its name implies, however, when the emergency ended and the economy rebounded, the program was shut down.

The Emergency Nursery Schools foreshadowed future federal policy toward early education. The federal government would offer free crisis-oriented education and other comprehensive services, but they would only be available to children in severely under-resourced communities. The most notable program was Head Start, established in 1965.

In a 1940 speech, Florence Kerr, Assistant Administrator in the Federal Emergency Relief Administration and Works Progress Administration recognized the value of an early education program:

“…someday we will have them [schools for young children] in every community, not under the WPA but as a part of our regular school system. We are just carrying the torch, showing communities what they can do.”— Kerr, 1940, cited in Arboleda, 2019, pp. 92-93.

Credit: Gordon Parks, Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Paths Merge, But Only Momentarily

The only time in history when the U.S. government funded an integrated child care and early education program was during WW2. The Lanham Act child care program was also the only federal child care early education provided to children regardless of their family income. However, this WW2 program was only available to families living in war-impacted communities or working in war industries, and was stopped shortly after the war.

Publicly funded education child care is possible when the Government is motivated to make it happen as it was during WW2, and it is now, but only families of the U.S. military are guaranteed access to federally subsidized integrated care and education regardless of their income.

Many mothers who worked outside the home before and during WW2 continued to do so, and many more mothers would join their ranks. Between 1940 and 1951, the percentage of employed mothers more than doubled, from 11 to 28 percent. Well aware of these changes and the growing demand for child care, federal leaders nevertheless reverted to framing separate policies for child care and education.

“The closing of child care centers throughout the country certainly is bringing to light the fact that these [Lanham] centers were a real need. Many thought they were purely a war emergency measure. A few of us had an inkling that perhaps they were a need which was constantly with us, but one that we had neglected to face in the past.…” — from “My Day,” a column by former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, September 8, 1945

Child Care Remains a Private Problem to Solve

“The fact that many mothers are employed, and that this is likely to be a permanent feature of our economy, make it of interest to society to examine the facilities available for the care of their children.” — U.S. Women’s Bureau, (1953), Bulletin No. 246, p. 11

Federal leaders were somewhat less disparaging toward working mothers—many more of whom were White and from middle-class communities in the years after WW2, but they stepped back from any responsibility for ensuring that child care was available and affordable. Instead, federal support for child care was limited to a welfare-linked service for a small portion of women from under-resourced communities. The federal government left other women to meet their own needs in the expanding (and increasingly commercial), private market, where personal finances and community supply determined the options.

In response to a broad-based advocacy campaign, the U.S. government came close to providing a national system of unified care and education when Congress passed the bipartisan Comprehensive Child Development Act of 1971. However, President Nixon vetoed the bill, stating that it would “weaken the family.”

Reflecting on the child care dilemma in our country, Representative Shirley Chisholm, the first Black U.S. Congresswoman noted:

“…discrimination against women and indifference to the poor are at the center of this country’s reluctance to expand its support for childcare programs. Woman’s place is in the home—so the attitude goes—and if women choose to work, then they’ll have to make the necessary arrangements themselves.” — Roby, 1973

Read The New York Times account of President Nixon’s veto of the Comprehensive Child Development Act, December, 1971.

Read How Politics Killed Universal Child Care in the 1970s by Jennifer Ludden, NPR, October 13, 2016.

Credit: T. J. O’Halloran, Library of Congress (1965).

Policy Choices Maintain the Division Between Child Care and Education

In the 21st century, the need for reliable child care is experienced by the vast majority of families who also want early education for their children. And the idea that child care is a custodial service, but not a learning environment, runs counter to scientific evidence about how and when children learn.

Unfortunately, federal early care and education policies continue to reinforce and fortify the boundaries between care and education. By providing more stable and generous funding for educational programs (such as preschool and Head Start) than for child care, the government signals that it values education more than care, reinforcing this distinction across society.

Creating and maintaining differences within the care and education sector between public preschool, Head Start, and child care has led to competition for scarce resources. Programs are pitted against each other, ultimately reinforcing and even increasing inequities for children, parents and the ECE workforce. Divisions within the sector also make it more challenging to leverage collective power and pressure policymakers to enact a vision of a more integrated early care and education system.

Entrenched systems are difficult to overcome, even in the face of evidence that they no longer work and cause harm. The division between child care and education has never worked and still causes harm, yet policies continue to reinforce this division. History reminds us that policies are created by people and can be changed by them as well.

Advocates have championed integrating care and education for decades. In 1973, historian Margaret O’Brien Steinfels wrote:

“Day care must be more than custodial; it must be developmental and educational. This point is obvious except to those who see day care primarily as a means of reducing welfare rolls.” — Steinfels, 1973

In 1989, developmental psychologist Emily Cahan wrote:

“As we enter into an era in which child care has, for the first time, become a widely discussed political issue, we must remain mindful of the historical persistence of a tiered system of child care and education.” — Cahan, 1989

Credit: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment

Policy Creates and Maintains Workforce Inequities

Working with young children has always been universally undervalued and underpaid, and early care and education services in the United States have always been substantially subsidized through the low pay of and inadequate support for the workforce. Nonetheless, even within the sector, there are different treatments of the workforce.

Historically, child care for the children of working mothers has been labeled “custodial” care. As a consequence, this workforce was seen as less skilled and paid less than those employed in programs like kindergarten or nursery school, which have been viewed as educational. Those referred to as kindergarten, nursery school, or preschool teachers were also offered more opportunities to advance their skills than child care workers. These divisions between care and education services have been maintained and bolstered by differential funding and regulations defining program purposes, workforce qualifications, and job duties.

Today, those working in programs regulated and funded as child care versus education continue to face the greatest penalties in compensation, working conditions, and opportunity to advance their skills. These penalties fall most heavily on Black educators and others from historically under-resourced communities who are more likely to be classified as child care workers providing services in the private market.

The penalties obscure the fact that child care workers educate children and preschool teachers provide care. Parents, and increasingly policymakers, understand this reality, and yet, while expectations of child care workers rise, seldom does their pay or status.

There is not only a pay penalty for working in “child care” compared to public preschool, but within publicly funded preschool, there are wage and benefit penalties for those working in community-located programs compared to those working in school-based settings, even within the same public preschool system (Whitebook et al., 2018).

Read Why do parents pay so much for child care when early educators earn so little?

Read Racial Wage Gaps in Early Education Employment.

Explore Contemporary advocacy and organizing for early educators.

Credit: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, 2020.

What’s in a Name?

The definition of the day nursery refers to the background of the children and does not refer to the type of care offered to them. — Beer, 1957

Whether you call it a day nursery or kindergarten, a family care home, a nursery school or preschool, care and education occur in all of these settings. And whether those working with children each day refer to themselves as child care workers, family child care providers, preschool or early childhood teachers, teacher assistants, or caregivers, they provide both care and education.

Names make a difference, but they don’t tell you whether the service children receive is care, education, or both, nor do they tell you about the training, experience, or skill of the person providing them. Instead, they indicate how much a provider is paid, who the program serves, and whether parents shoulder most of the cost or receive government subsidies. The names don’t tell you how much parents sacrifice to pay for it, but they do tell you we have an overly complicated system, riddled with disparities that needs to be completely overhauled.

Science has provided “proof” of what early educators—and parents and grandparents in every culture—have long known. Babies are learning right from the start, and young children before school are learning when they play and when they are being taken care of. And as the COVID-19 pandemic made clear, older children are cared for at school, and child care providers play a key role in young children’s education.

Read Is child care safe when school isn’t? Ask an early educator.

Credit: Child Care Providers United Staff, 2022.

From Necessary Evil to Public Good

There remains a chronic tendency to focus only on one part of the child care equation—parents, providers, or children—instead of all three. Or solutions focus on stop-gap measures that disregard “the big picture.” In effect, the present system pits the needs of these three different constituent groups against each other. It’s time for the country to provide a coherent national care and education system that meets the needs of children, parents, and providers. — National Center for the Early Childhood Workforce, 1993

Today, the early care and education system of the United States fails most children, their families, and those who educate and care for young children. Even at its most ambitious during WW2, it was underfunded and short-lived.

The longstanding division between care and education in our system is a social construct informed by racist and gendered assumptions and practices that are reinforced by outmoded public policies.

At a time when even two jobs are not enough to support a family and in the face of irrefutable evidence about the importance of the early years, the shortcomings of early care and education in our country are outrageous. It would be tempting to call them laughable, if they were not so terribly harmful to the children who are losing out and so damaging to the economic security and well-being of the adults in their lives.

New policy pathways for early care and education must be laid. They are necessary for the good of us all.