California has proposed a broad expansion of transitional kindergarten (TK), a school-based early learning program serving four-year-olds. This improvement will make TK universally available to all four-year-olds by 2025, framed as a pillar of the state’s early care and education (ECE) system.

As the expansion is expected to create a need for thousands of new TK teachers, California is exploring options to staff this change, including the creation of a new PK-3 ECE Specialist Credential.

Early educators in home- and center-based settings are highly qualified to work with four-year-olds and possess, on average, more than 10 years of experience in the sector. If California provides equitable access to TK jobs for the current ECE workforce, we estimate that the median center-based teacher with a bachelor’s degree could see their salary double with a job in TK. For teachers with a bachelor’s degree operating a home-based family child care (FCC) program, their take-home pay could increase nearly two and a half times. In other words, a center-based teacher could see an increase of roughly $42,000 in annual pay, and an FCC provider could see an increase of about $49,000.

Directors and administrators in child care centers may also take an interest in teaching TK; however, their salary gains would be somewhat lower. Though still a meaningful raise, a director with a bachelor’s degree could potentially earn $25,000 more as a TK teacher.

While many early educators may prefer to continue teaching in their current settings—and leaving would undoubtedly have a ripple effect—the lack of investment in teacher wages outside of TK virtually guarantees that many would explore this new career choice. As of this writing, however, the proposed pathways to a PK-3 teaching credential do not offer a way for experienced early educators with a bachelor’s degree—those teachers with the deepest knowledge and experience teaching four-year-olds—to immediately apply for the credential.

Pathways exist for experienced K-12 teachers in private schools to apply for a Multiple Subject Credential without additional training, but early care and education is not accepted as a qualified teaching setting. Today, neither the pathways to the Multiple Subject Credential nor the proposed pathways to a new PK-3 credential provide an equivalent “private school” option for experienced early educators to earn the credential. Instead, proposals require early educators to gain additional qualifications. The absence of an equitable and immediate pathway for early educators to teach TK both devalues the ECE workforce and makes it much harder to find qualified lead teachers for TK.

Instead, California should take action to create a direct pathway for the 40,000 early educators who already teach young children and hold a bachelor’s degree. Within that group, there are 17,000 current early educators who possess a bachelor’s degree, a child development permit at the teacher level or higher, and six or more years of teaching experience in early childhood settings. (More detail on our estimate is provided in the section below.)

California’s highly experienced early educators deserve the opportunity to double their salary and have their education and experience valued on par with teachers of older children, rather than seeing the state’s historic investment offer them nothing unless they pursue additional qualifications.

In this data snapshot, we provide findings from the 2020 California Early Care and Education Workforce Study. The Center for the Study of Child Care Employment (CSCCE) surveyed more than 7,500 early educators in both family child care programs and child care centers, along with an exploratory sample of 280 transitional kindergarten teachers. Our data provide the most accurate and up-to-date picture of wages and benefits for the ECE workforce. For comparison, we have constructed a composite estimate of TK wages and benefits using a combination of data from the U.S. Census, the Bureau of Labor Statistics, and the California Department of Education (CDE).

TK Employment Could Offer a Sizeable Raise for the ECE Workforce

Wages

Policymakers should prioritize public investment in wage growth across California’s mixed-delivery system, not only in school-based settings. In the absence of funding for such a change, TK wages will almost certainly outcompete prevailing ECE wages. Table 1 compares current median ECE wages to the average minimum salary (median is unavailable) offered by local education agencies (LEAs), as well as the median TK wage. For wages of center-based directors, see Table 6 in Appendix II.

For early educators hired as TK lead teachers, the size of their pay increase would depend on whether or not they earn the same as current TK-12 teachers—or whether they would be hired at the bottom of the LEA pay scale. For FCC providers, earning the median TK wage in California would grow their earnings nearly two and a half times. Earning even the minimum certificated salary would increase their earnings 1.5 times. For center-based teachers, earning the median TK wage could mean a twofold increase in pay, while coming in at the bottom of the pay scale would mean earning about 1.2 times their previous salary.

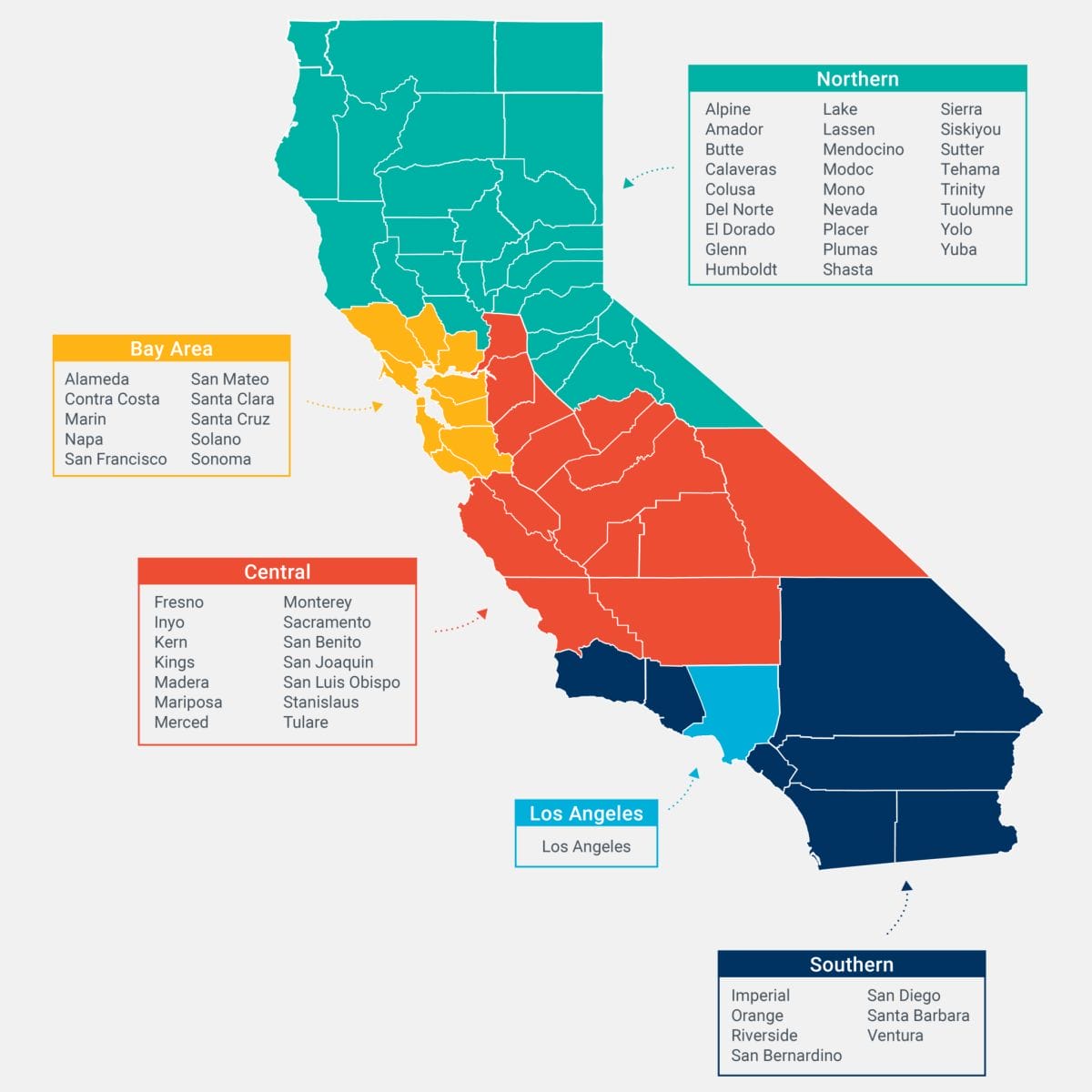

Table 2 models the hypothetical wage growth for a current ECE provider with a bachelor’s degree in both dollar and rates of growth (i.e. a salary doubling would be growing 2.0 times, or 2.0x). These figures also vary by region, with the largest potential bump for center-based teachers in Los Angeles. Among FCCs, providers in Northern California would see the biggest raise. The ECE workforce in the Bay Area would see the smallest pay increase in both cases.

Benefits

In addition to low wages, many jobs in early education offer insufficient benefits. By comparison, school-based teachers can count on access to health insurance and retirement plans in virtually all public districts in California (see CalSTRS and CalPERS).

The California ECE Workforce Study asked family child care providers and center directors about benefits in their programs. While FCC providers reported on health and retirement benefits they accessed themselves, center directors reported on employer-sponsored offerings for their teaching staff.

Family child care providers typically access benefits such as health care by qualifying for Medi-Cal or purchasing a plan on Covered California—unless they are able to enroll with a spouse or family member. Because they lack employer-sponsored benefits, they face a substantial benefit gap compared to TK teachers: a 10-percentage-point gap in health coverage and a 66-percentage-point gap in retirement savings. Table 3 provides a breakdown of FCC provider access to benefits from any source, including from a spouse.

Some center-based educators do have employer-sponsored benefits. However, child care centers are less likely to provide health or retirement benefits to their staff than school districts. Only 70 percent of child care programs provide health care to their teachers, and only 51 percent offer retirement. Virtually all K-12 teachers in public school districts have access to benefits through CalSTRS and/or CalPERS. Table 4 provides a breakdown of benefits offered in child care centers in California by region.

While nearly one in three child care centers does not offer health insurance to its teaching staff, the majority of teachers (93 percent) do ultimately obtain health insurance. Similar to FCC providers, some center-based educators access health benefits through family members, Medi-Cal eligibility, or Covered California.

A Note on Paid Time Off

Paid sick days and holidays are standard for TK-12 schools, and the majority of center-based teachers (96 percent) have one or more forms of paid days off. In contrast, only one half of family child care providers include paid leave days in their contracts with families. In other words, if they fall sick and shut down for even a brief interval, those days represent a net loss.

17,000 Current ECE Teachers Meet Rigorous Qualifications

Statewide, we estimate 24,700 educators were teaching in FCCs and 60,800 in centers (including school-based preschools) as of late 2020. Thousands more work as directors and administrators or in other roles, such as teaching assistants, coaches, etc. Among those currently working in teaching roles, there are at least 41,000 with a bachelor’s degree, of which 7,400 teach in an FCC setting. Additionally, we estimate nearly 17,000 current early educators have all of the following:

- A bachelor’s degree;

- A major in early childhood education, child development, or an interdisciplinary major;

- Six or more years of experience in ECE settings (preschool or younger); and

- A California Child Development Permit, at the Teacher level or higher.

While a subset of these qualifications would likely be sufficient to thrive as a TK teacher, this list represents a comprehensive set of early childhood qualifications. A school district hiring for TK might consider some combination of the above experience to identify high-quality applicants from the ECE field. As it currently stands, TK teachers who hold a Multiple Subject Credential need only have 24 units of early childhood education, and this requirement can be waived.

Among directors and teaching assistants, there will be additional individuals who would meet the criteria. Furthermore, there are thousands of highly qualified early educators who have taken jobs outside the field in order to earn a living wage. A credentialing pathway that values teaching experience in early care and education could bring these educators back to the preschool jobs they could not afford to keep. Ultimately, the figure of 17,000 is an underestimate of the true ECE workforce qualified to teach TK, but it represents the current workforce with a rigorous set of ECE qualifications that school districts might consider.

We urge California authorities to establish pathways that leverage this extensive practical experience and education that thousands of early educators already possess. Creating a straightforward path to the PK-3 credential would provide a pool of at least 17,000 highly qualified and prepared ECE teachers for children in TK and offer life-changing opportunities for thousands of educators to earn a living wage.

Appendix I: Methodology

CSCCE’s 2020 California ECE Workforce Study provides the most accurate picture of prevailing ECE qualifications and wages in the state. From October through December 2020, we surveyed representative samples of approximately 2,000 center administrators and 3,000 home-based FCC providers, as well as non-probability samples of about 2,500 center-based teaching staff members and 280 TK teachers.

This snapshot focuses exclusively on a comparison among FCC providers, teachers in centers, and TK teachers. Center administrators and center aides are excluded from our analysis.

Map of Regions in California

Wages

In the California ECE Workforce Study, center-based wages were self-reported. For center-based educators, we asked about wages directly; for FCC providers, we estimated wages using a combination of household income and proportion of income earned working with children.

Minimum wages in school districts derive from the authors’ analysis of the California Department of Education (CDE) Form J-90 data by district, excluding data from districts with no elementary schools. Salaries are weighted by the number of certificated staff per local education agency (LEA). Median TK wages are a composite estimate of four sources, which the authors analyzed by region and adjusted for inflation to match our data collection window beginning in October 2020:

- Weighted average Form J-90 salary data for K-12 actual wages across LEAs in the 2019 school year; median salary was not available in the source data;

- Median Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) May 2021 May 2021 State Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates for kindergarten teachers;

- Median BLS May 2021 wage estimates for elementary school teachers; and

- Median TK sample in the 2020 California ECE Workforce Study.

For further detail on the median TK wage estimate, see Table 7 in Appendix II.

A Note on Minimum Wages

Our data were collected in 2020, when California’s minimum wage was $12 per hour for employers of 25 or fewer staff members and $13 for larger organizations. As of 2022, both minimums have risen by $2 per hour. The policy may have impacted some early educators; however, we estimate that 85 percent of center-based educators were already earning at least $15 per hour in 2020. Their wages may be unaffected by the policy change, just as FCC providers, who are self-employed, will see no impact on their earnings.

Benefits

Table 3 provides estimates for benefits in use by early educators in California. The figures for health insurance coverage and retirement savings are self-reported by FCC providers from any source. The kindergarten average in Table 3 leverages the authors’ analyses from multiple sources, since the California ECE Workforce Study included only a small sample of 280 TK teachers for comparison. For health care, we accessed microdata from the 2019 American Community Survey 5-Year Sample via IPUMS. For retirement benefits, we analyzed microdata from the 2017-2021 Current Population Survey. In both cases, our analysis focused on adults living in California with occupation code 2300 Preschool and Kindergarten Teachers or 2310 Elementary and Middle School Teachers. The latter was included to mitigate potential bias in code 2300 due to the inclusion of preschool teachers. Both figures may include private school teachers.

Table 4 reflects the proportion of centers offering benefits to lead teachers on their staff, rather than the number of teachers currently taking up the benefits. These findings are reported by directors and administrators of child care centers. The kindergarten estimate of 100 percent offering benefits reflects California’s provision of benefits for K-12 teachers teaching in public schools. For instance, benefits are offered via the California Public Employee Retirement System (CalPERS) and the California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS). Some school districts operate their own program(s) in lieu of participating in CalPERS and/or CalSTRS, but the vast majority are served through these two state-sponsored systems.

Appendix II: Data Tables

Suggested Citation

Powell, A., Montoya, E., Austin, L.J.E., & Kim, Y., (2022). Double or Nothing? Potential TK Wages for California’s Early Educators. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. https://cscce.berkeley.edu/publications/data-snapshot/double-or-nothing-potential-tk-wages-for-californias-early-educators/

Acknowledgements

This publication was produced with grants from the David and Lucile Packard Foundation and the Heising-Simons Foundation. Additionally, we draw on findings from the 2020 California Early Care and Education Workforce Study, a multiyear project generously supported by First 5 California, the California Department of Education, the Heising-Simons Foundation, and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation and implemented in partnership with the California Child Care Resource & Referral Network.

Many thanks to our Research Director, Abby Copeman Petig; to our colleagues Hopeton Hess and Wanzi Muruvi; to our editor, Deborah Meacham; and our web creator, Tomeko Wyrick. Title page photography courtesy of Brittany Hosea.

The views expressed in this commentary are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent collaborating organizations or funders.

Note: This publication was updated on October 4, 2022. Table 2 previously represented changes in incomes in percentage terms; the new version uses rates of growth (eg. “increased by 2.4 times, or 2.4x”).