You may have heard about the New Mexico early educators whose activism through the organization OLÉ spurred a statewide referendum in 2022 to increase their pay. Or the win by family child care providers in California, whose new union contract will improve their subsidy reimbursement rates, among many other benefits.

But do you know about two movements nearly 50 years ago that were also led by women who aimed to improve their wages and working conditions?

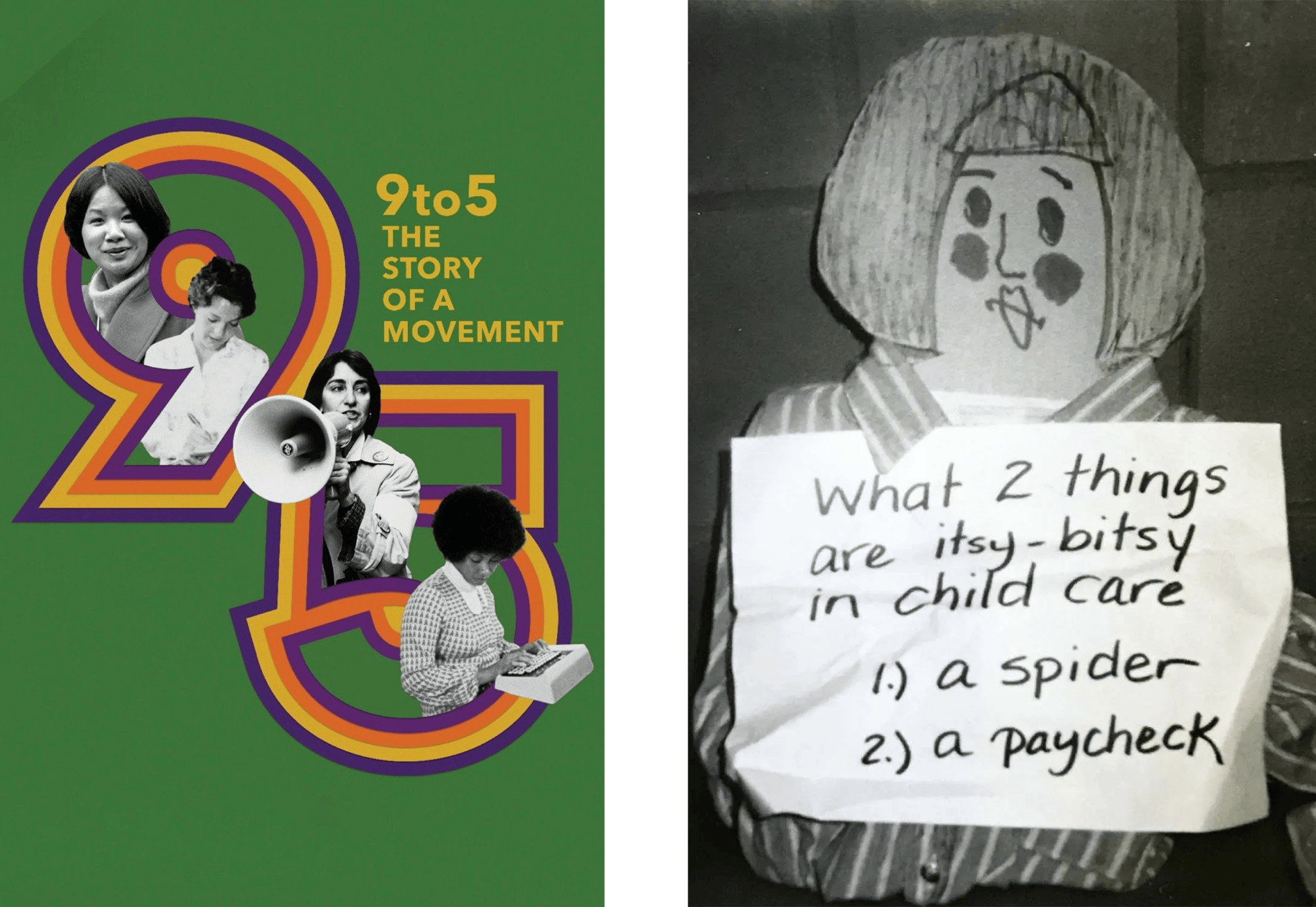

Watching the documentary, 9 to 5: The Story of a Movement (premiered on PBS in 2021), I couldn’t help but be struck by the similarities between this story about U.S. secretaries organizing and that of the Worthy Wage movement for early childhood educators.

The Worthy Wage movement changed my life and the lives of women around me. Entering the workforce when options for women were limited, we welcomed the women’s movement of the 1970s. But as that movement focused on expanding opportunity and breaking “glass ceilings” in male-dominated professions, hundreds of thousands of women working as secretaries, nurses, teachers, and child care providers were left behind. Feeling invisible in both the women’s movement and the labor movement, child care providers created their own movement—just like the secretaries who founded the organization 9 to 5 in the 1970s, a struggle that inspired the 1980 film and Dolly Parton’s hit song of the same name.

Despite the profound impact of these movements, they share a forgotten history. As Karen Nussbaum, co-founder of 9 to 5, noted in the documentary, “People don’t ask me about 9 to 5.” Similarly, early childhood educators of today tend to know little, if anything, about the history of child care activism in the latter part of the 20th century.

There are other similarities between the two movements. Women who may never have self-identified as “leaders” learned about social justice and activism through families and friends engaged in other movements, like the civil rights and anti-war movements. Additionally, feminist writings and consciousness raising about the roles of women in the 1970s, along with the women’s liberation movement, set the stage for both movements. We didn’t know about “organizing” per se, but we knew about bringing women together. Organizing both secretaries and child care workers started with small, informal relational meetings. As noted in the 2021 PBS documentary, the secretaries’ organizing strategy was: “Ten women got together; that’s enough…. Someone was assigned to bring the cookies.”

My initiation into the child care Worthy Wage movement was a Sunday brunch group of child care teachers sharing a meal around someone’s kitchen table. In these small gatherings, women began to give voice to the value of their work and to challenge the widely held view that our roles were merely to be “in service” to others, whether they were bosses or families with children. We were seeking more than better wages and working conditions: we wanted respect. The secretaries put it this way: “We are referred to as ‘girls’ until we retire without pensions.” Child care teachers and family child care providers found unity in our disdain of the moniker “babysitter.”

We knew we were a part of a movement by the spontaneity of small groups like ours popping up in different places around the country, doing similar things: finding one another, inspiring one another, growing momentum for change. Communication among our groups and out to the wider world needed to be amped up. Like the secretaries, we used mimeographed newsletters that we wrote, copied, and shared with one another. We made flyers that we handed out on street corners, at subway stops, and in other public spaces. We planned public events and demonstrations where we used the “tools of our trade” to amplify our messages. [Discover stories, songs, flyers and more: ECHOES.] For example, the documentary showed secretaries costumed as bottles of white-out; child care providers created life-sized dolls to hold our signs. Unfortunately, small successes were too often met with no follow-up plan, and the need for more training became apparent. Both movements turned to the Midwest Academy to learn more about organizing. Intentional leadership development became key to sustaining our movements.

Organizing continued to be relational, but we became more focused, building on individual strengths and recognizing leadership in everyone. We taught ourselves skills that were required of us as organizers, but not part of our professional training, like how to be public speakers and how to influence public policy. In child care, we developed curricula to share what we were learning with others. Both movements engaged in similar strategies: we wrote songs and sang; we handed out leaflets; we wore buttons bearing slogans like “Give a Child Care Worker a Break.” We conducted surveys as a way for women’s voices to be heard about the problems they faced, and these surveys in turn became a tool for calling for more respect, demanding changes, and identifying opportunities. While secretaries crafted a Bill of Rights for Office Workers, child care providers developed the Principles of a Worthy Wage Campaign.

Both secretaries and child care teachers were trying to build organizations they wanted to be part of and organizations that looked like the workforce whose issues they were addressing. Among other things, this meant addressing racial barriers and building leadership among Black and Brown members of our workforces. Implicit bias, systemic racism, and White supremacy ruled the day then as now, and organizers who were people of color had it tough in both movements. All of us recognized that we were in our struggles “for the long haul.” We looked to labor unions to help grow our power, but both secretaries and child care workers knew we wanted something different than the male-dominated scene in the unions in the 1970s. The effectiveness of unionization and the impact of public policy, however, were major differences in the two movements.

The 9 to 5 movement successfully created a union called District 925 under SEIU, and members were given the autonomy they desired. Yet, in the face of serious union-busting efforts by management, garnering the required number of “yes” votes to join the union was not easy. Meanwhile, the structure of the child care industry made unionization a less-than-successful strategy. Ours was an industry of many small “shops,” each independently run and adhering to rules and regulations established by the government that varied from state to state. While secretaries had clear “bosses” who held the power and resources to improve wages and working conditions, there was typically no clear “management” with whom to bargain a contract in child care. Like today, resources were limited by what parents could afford to pay and/or what the government was willing to subsidize. Owners and child care program directors were often allies of the movement. There were a few small-scale successes, especially where child care centers were a part of a larger organization that was unionized, where there was an additional funding source, or where independent unions were created. For secretaries, union negotiations could result in the need to take direct action, and walkouts became a powerful strategy. For child care workers, however, walkouts are fraught with concern for the well-being of children and working families. Some child care programs did close down for Worthy Wage Day, but the impact was different than a work strike.

Child care teachers as early as the 1980s began creating guidelines for programs striving to improve working conditions. These guidelines eventually evolved into Model Work Standards, a version of which exists today. But what we did not encounter to any significant extent was the sexual harassment experienced by our counterparts. We owe a debt of gratitude to the secretaries who took on this issue and brought about major improvement for all working women. The power of those efforts and the pervasiveness of the problem garnered secretaries a national champion in the 1980 film comedy (and its theme song), 9 to 5, starring Jane Fonda, Dolly Parton, and Lily Tomlin, which turned a national spotlight on their stories. We’re left to wonder what a difference a champion for child care could have made and what messages a movie or an anthem would have carried.

When it comes to public policy, anti-wage discrimination, and price-fixing, laws were clearly being violated in major businesses like banks and insurance companies that employed hundreds of secretaries. Secretaries, in turn, were able to use the legal system to win raises and embarrass bosses. During this same time period, however, government generally took a “hands off” approach to child care. The role of caring for children was regarded as a private family responsibility, even though it was (and still is) a major driver of the economy by providing an essential service to working parents. The federal and state governments merely established basic licensing rules and regulations, along with minimal financial support for very low-income families.

So what do these two movements teach us today? Women have yet to earn equal pay, and low wages continue to plague service workers, even as this sector experiences the most significant job growth. Too many families are struggling to make ends meet, and the injustices reflected in disparities between White people and people of color are increasingly and necessarily part of the public dialogue. The years of social and economic upheaval due to a global pandemic have only compounded these issues. In the documentary, Karen Nussbaum wondered aloud, “What happens to consciousness? Does it stay underground ready to emerge again?” There is evidence all around us that early childhood educators throughout the country are rising up once again to claim our power to create change. We have new tools and new leaders—and we have a history of activism to lean upon and to inspire us.