Despite a growing understanding of the importance of early learning and development and the expansion of quality improvement initiatives over the past 15 years, the wages we describe in this report reflect how little has been done to address the economic well-being of educators themselves.

Early educators’ wages are still low. In fact, we estimate that teachers with bachelor’s degrees who work in California child care centers saw a decline in actual wages of 1 to 2.5 percent between 2006 and 2022, despite a 35-percent increase in the state minimum wage over the same period.

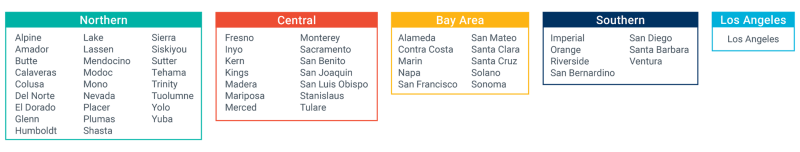

Scroll over the map to learn about median annual full-time wages across the state

Key Findings

Income and Wages

- Small FCC providers (serving up to eight children) reported the lowest wages among the ECE workforce, with an annual income of $16,200-$30,000. Large FCC providers (serving up to 14 children) reported earning $40,000-$56,400, similar to the salaries of center teachers and directors.

- Regardless of program size, FCC providers do not see a bump in income for attaining a bachelor’s degree.

- On average, FCC providers holding contracts with the state of California or federally funded Head Start reported higher incomes than those in voucher-subsidized programs or programs without public funding, regardless of program size.

- For child care centers statewide, median hourly wages are $16 per hour for assistant teachers, $19 per hour for teachers, and $26 per hour for directors.

- Center directors and teachers received modest income boosts moving from an associate to a bachelor’s degree, while assistant teachers see little or negative impact.

- Across job roles and education levels, the median wages of center-based educators fall short of the national median wage of workers with comparable education in all occupations. The median wage of a center teacher with a bachelor’s degree or higher in California is $20 an hour, while workers with a bachelor’s degree across occupations earn a median hourly wage of more than $34.

- Throughout California, early educators working in state-contracted centers reported higher wages than those in centers with other funding sources.

Health Coverage, Retirement Benefits, and Paid Time Off

- FCC providers, both small and large, are less likely than center directors or teaching staff to have health coverage. Among FCC providers, the most commonly reported source of insurance coverage was through a spouse, partner, or parent.

- Only about one fifth of small FCC providers and one quarter of large FCC providers reported any retirement savings.

- Less than one half of FCC providers, regardless of program size, reported having paid time off.

- Center directors and teachers working in Head Start or Title 5 programs were more likely to have health insurance (and to access employer-sponsored insurance) than those in voucher-subsidized centers or centers with no public funding. Directors and teachers in centers with no public funding were the least likely to utilize employer-sponsored health insurance.

- About one half of center directors and teachers and about two fifths of assistant teachers reported having retirement savings. Regardless of their role, educators in publicly contracted centers are the most likely to report having retirement savings, while those in voucher-subsidized programs are the least likely.

- The vast majority of center directors, teachers, and assistant teachers reported having paid leave.

Recommendations for Policymakers

1. Ensure that all state policies are made in consultation with early educators.

- Establish practices that center the experiences, intellect, and leadership of early educators.

2. Articulate compensation standards for all educators across ECE program settings.

- Establish a wage floor so that, at a minimum, no one working in a child care classroom or family child care home earns less than the regionally assessed living wage and articulate minimum benefit standards (health insurance, paid leave, retirement).

- Compensation standards for center- and home-based educators should scale up from the floor to account for job role, experience, and education levels, up to parity with similarly qualified TK and elementary school teachers—and compensation should be provided for non-contact hours (i.e., paid preparation/planning time).

3. Develop a methodology to identify the true cost of providing high-quality ECE programs in both center- and home-based settings that includes established compensation standards.

- Use the true cost to set appropriate levels of funding for a publicly funded ECE system, rather than basing funding on market rates.

- Include adjustments for cost of living in the methodology.

4. Establish requirements and dedicate sufficient public funding for all programs to meet wage and benefit standards. Require and monitor adherence to those standards as a condition of funding.

5. Prioritize stable contract-based funding arrangements for home-based providers and centers.

- Contracts should guarantee a base funding amount—accounting for a specific number of publicly funded spots, rather than using volatile enrollment or attendance levels.

- Contracts should specify the portion of funds to be used for compensation.

6. Fund and make publicly available current and longitudinal research on the ECE system and workforce, including compensation.

- Include a plan to require and fund full participation in state workforce data systems for all members of the ECE workforce employed in school-, center-, and home-based child care settings.

- Examine data to identify and remedy wage gaps and pay inequities.

- Report the utilization and impact of funding for compensation and other investments to inform future policies and resource allocation.