Early Educator Pay & Economic Insecurity Across the States

Download The Early Childhood Educator WorkforceThe historical and pervasive undervaluing of labor performed by people of color and especially women in the United States, combined with reliance on a market-based system that depends mostly on parents’ ability to pay, has made early care and education one of the most underpaid fields in the country. As a result, early educators face severe pay penalties for working with younger children in all states, with poverty rates an average of 7.7 times higher than teachers in the K-8 system (see Early Educators Face a Pay Penalty for Working With Children 0-5).

While wages paid to early educators overall are low, additional disparities within the workforce itself cause greater harm to certain populations. As we have previously documented, across different types of settings and job roles in the sector, wage disparities are linked to funding source, age of children, and racial discrimination.1Whitebook, M., McLean, C., Austin, L.J.E., & Edwards, B. (2018). Early Childhood Workforce Index – 2018. Berkeley, CA: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved from http://cscce.berkeley.edu/topic/early-childhood-workforce-index/2018/. For example, we found that among center-based teachers, those working full-time exclusively with infants and toddlers are paid up to $8,375 less per year than those who work with preschool-age children. And this disparity is especially harmful to Black women working in centers, as they are more likely than their peers to work with infants and toddlers, and to Black, Latina, and immigrant women working in home-based settings, where a large share of infants and toddlers are in care. Importantly, we also identified a racial wage gap in which Black early educators are paid on average $0.78 less per hour than their White peers. The pay gap is more than doubled for Black educators who work with preschool-age children ($1.71 less per hour compared with their White peers) compared with the pay gap for Black educators who work with infants and toddlers ($0.77 less per hour compared with their White peers).2Austin, L.J.E., Edwards, B., Chávez, R., Whitebook, M. (2019). Racial Wage Gaps in Early Education Employments. Berkeley, CA: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved from https://cscce.berkeley.edu/racial-wage-gaps-in-early-education-employment/.

Black early educators are paid on average $0.78 less per hour than their White peers.

These conditions reflect the status of the workforce coming into the pandemic and stand in stark contrast to the narrative of early educators as essential to children, families, and the economic system in the United States. Given what we are learning about the financial devastation and health risks the ECE sector and its workforce are experiencing in the midst of the pandemic, we can expect that these conditions will only worsen going forward, barring substantial federal and state intervention.

“The loudest voices in the current conversation about child care are working parents and politicians who recognize, and in some cases demand, child care as the key to reopening the economy, but what about care providers themselves? Ultimately, the economy will reopen, but it can do so in either of two ways: with long-overdue government intervention and support for the well-being of families and providers alike or on the backs of some of the poorest and most marginalized women workers, who will somehow make things work by bearing the burden in every way.”

California3Quote from CSCCE survey of teachers. For more information about the study, see Doocy, S., Kim, Y., & Montoya, E. (2020). California Child Care in Crisis: The Escalating Impacts of COVID-19 as California Reopens. Berkeley, CA: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved from https://cscce.berkeley.edu/california-child-care-in-crisis-covid-19/.

National Context: Early Educator Pay

The most recent data from the Occupational Employment Statistics (OES), compiled in 2019 and prior to the onset of the pandemic in early 2020, shows little change since the 2018 Index. Wages paid to early educators remain substandard across the sector and in comparison to other occupations and teaching jobs that are also underpaid relative to their qualifications and skills (see Figure 2.1).4Allegretto, S., & Michel, L. (2020). Teachers pay penalty dips but persist in 2019. Washington, D.C.: Economic Policy Institute. Retrieved from https://www.epi.org/publication/teacher-pay-penalty-dips-but-persists-in-2019-public-school-teachers-earn-about-20-less-in-weekly-wages-than-nonteacher-college-graduates/.

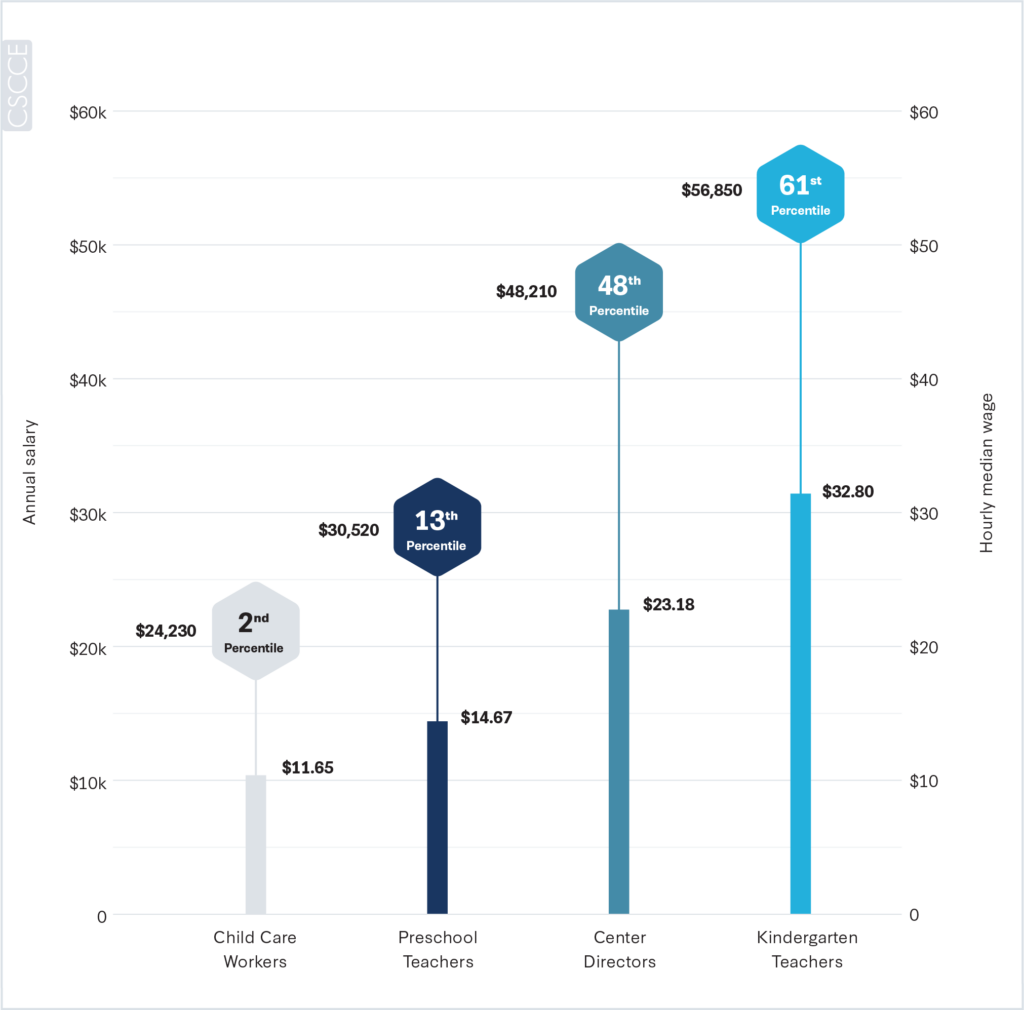

Figure 2.1

Median Hourly Wages, by Occupation, 2019

When all occupations are ranked by annual pay, child care workers remain nearly at the bottom percentile, unchanged since the inaugural 2016 Index.

Although child care worker wages increased more than other education occupations between 2017 and 2019, this 4-percent increase, adjusted for inflation, adds only $0.44 to the median hourly wage, which rose from $11.21 in 2017 (in 2019 dollars) to $11.65 in 2019 or about $915 on a full-time, full-year schedule (see Figure 2.2). Child care worker wages had seen a 7-percent increase between 2015 and 2017, reported in the 2018 Early Childhood Workforce Index, and child care workers continue to be one of the lowest-paid occupations nationwide. When all occupations are ranked by annual pay, child care workers remain nearly at the bottom percentile (see Figure 2.3), unchanged since the inaugural 2016 Index. Preschool teachers and directors of child care centers or preschools are also subject to low wages, particularly compared with teachers of school-age children.

Figure 2.2

Percent Change in National Median Wage, by Occupation, 2017-2019

Figure 2.3

Selected Occupations Ranked by Annual Pay, 2019

Note: All teacher estimates exclude special education teachers. Hourly wages for preschool teachers in schools only, kindergarten teachers, and elementary school teachers were calculated by dividing the annual salary by 40 hours per week, 10 months per year, in order to take into account standard school schedules. All other occupations assume 40 hours per week, 12 months per year.

Early Educators Face Profound Economic Insecurity

The work of teaching and caring for young children is highly skilled and complex, yet employment in early care and education has largely failed to generate wages that allow early educators to meet their basic needs. Instead, undertaking this work has been a pathway to poverty for many early educators and poses a risk to their well-being, with consequences extending to their own families and to the children in their care.5Johnson, A.D., Partika, A., Schochet, O., & Castle, S. (2019). Associations between early care and education teacher characteristics and observed classroom processes. Urban Institute. Retrieved from https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/101241/associations_between_early_care_and_education_teacher_characteristics_and_observed_classroom_processes.pdf; Cassidy, D.J., King, E.K., Wang, Y.C., Lower, J.K., & Kitner-Duffy, V.L. (2016). Teacher work environments are toddler learning environments: teacher professional well-being, classroom emotional support, and toddlers’ emotional expressions and behaviors. Early Childhood Development and Care, 187(11), 1666-1678. Early educators have continuously shown high rates of utilizing public income support programs — i.e., the Federal Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) — which may serve as a bellwether for the economic insecurity of this workforce.6Whitebook, M., McLean, C., Austin, L.J.E., & Edwards, B. (2018). Early Childhood Workforce Index – 2018. Berkeley, CA: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved from https://cscce.berkeley.edu/early-childhood-workforce-2018-index/; Whitebook, M., McLean, C., & Austin, L.J.E. (2016). Early Childhood Workforce Index – 2016. Berkeley, CA: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved from https://cscce.berkeley.edu/early-childhood-workforce-2016-index/; Whitebook, M., Phillips, D., & Howes, C. (2014). Worthy work, STILL unlivable wages: The early childhood workforce 25 years after the National Child Care Staffing Study. Berkeley, CA: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved from https://cscce.berkeley.edu/worthy-work-still-unlivable-wages/. And in several studies conducted across local communities and states, CSCCE has documented the impact low wages have on teacher well-being, particularly in the form of high levels of economic worry, including worrying about paying monthly bills, housing costs, routine health care costs, and even the ability to feed their families.7See the CSCCE Teachers’ Voices series, available at https://cscce.berkeley.edu/topic/teacher-work-environments/sequal/teachers-voices/.

“As a full-time teacher, I don’t make enough money to support myself. I have other gigs to help me pay bills and food.”

Marin County, California8Quote from CSCCE survey of teachers. For more information about the study, see Schlieber, M., Whitebook, M., Austin, L.J.E. Hankey, A., & Duke, M. (2019). Teachers’ Voices: Work Environment Conditions That Impact Teacher Practice and Program Quality — Marin County. Berkeley, CA: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved from https://cscce.berkeley.edu/teachers-voices-work-environment-conditions-that-impact-teacher-practice-and-program-quality-marin-county/.

Even in one of the wealthiest communities in the country, Marin County, California, the wages paid to early educators remain low, and the economic consequences are great. Less than a year before the onset of the pandemic, a survey of center-based staff in Marin County revealed that economic insecurity was widespread: three-quarters (75 percent) worried about paying routine monthly bills and expenses, including housing, and more than one-third (39 percent)worried about having enough food for their families. These circumstances were likely magnified for educators of color who were paid approximately $6,100 less per year on average than their White peers.9Schlieber, M., Austin, L.J.E., & Valencia López, E. (2020). Marin County Center-Based Early Care & Education Workforce Study 2019. Berkeley, CA: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved from https://cscce.berkeley.edu/marin-county-center-based-early-care-education-workforce-study-2019/.

COVID-19 Worsens Existing Economic & Health Insecurity for Early Educators

Early educators’ poverty-level wages are compounded by a lack of access to basic health and well-being supports like health insurance and paid sick leave. The pandemic brought into focus the severe consequences of these long-standing realities, as many educators have been forced to choose between a paycheck or their own health and safety and that of their families.

Many states have surveyed center directors and family child care owners to understand the magnitude of closures, financial distress, and the type of supports needed to stay open.1See Urban Institute (2020, September 11). A List of COVID-19 Child Care Surveys and Data Analyses. Retrieved from https://www.urban.org/policy-centers/center-labor-human-services-and-population/projects/list-covid-19-child-care-surveys-and-data-analyses. These studies documented widespread financial and health insecurity, such as the loss of already-insufficient income to cover operating costs (including staff wages), layoffs of teaching staff, and substantial worry about the health risks of continuing to provide ECE services. For example, a survey of family child care owners and center directors in Nebraska documented that a majority have been experiencing physical, cognitive, and emotional symptoms of stress, such as changes to sleep and eating habits or feelings of depression or anxiety, due to the pandemic.2Daro, A., & Gallagher, K. (2020). The Nebraska COVID-19 Early Care and Education Provider Survey II. Nebraska: Buffett Early Childhood Institute, University of Nebraska. Retrieved from https://buffettinstitute.nebraska.edu/-/media/beci/docs/provider-survey-2-080420-final.pdf?la=en. While these studies typically were unable to survey teaching staff directly, given the documented pay and economic worry pre-pandemic, it is reasonable to assume that many early educators have experienced similar types of economic, physical, and mental stress.

State-by-State: Early Educator Pay

Despite recent increases to pay in some states, early educator wages remain low in every state and the District of Columbia. Often ECE workers’ pay does not meet even conservative estimates of a living wage, as explored later in this section. Cross-state wage data underscore the persistent and urgent need to alleviate the financial burden by raising wages for early educators — of whom we demand so much but continue to offer so little. The following section presents state-level information on:

- Median wages across ECE occupations (child care workers, preschool teachers, and center directors) and how they compare to overall median wages in a state as well as to kindergarten teachers’ pay;

- Changes in median wages across ECE occupations from 2017 to 2019;

- Median wages across ECE occupations, adjusted for state cost of living;

- A comparison of child care worker wages and a living wage in every state; and

- A comparison of pay and poverty rates between early educators and K-8 teachers.

For more detailed information on each state and territory (where available), see Appendix 2: Early Educator Workforce Tables.

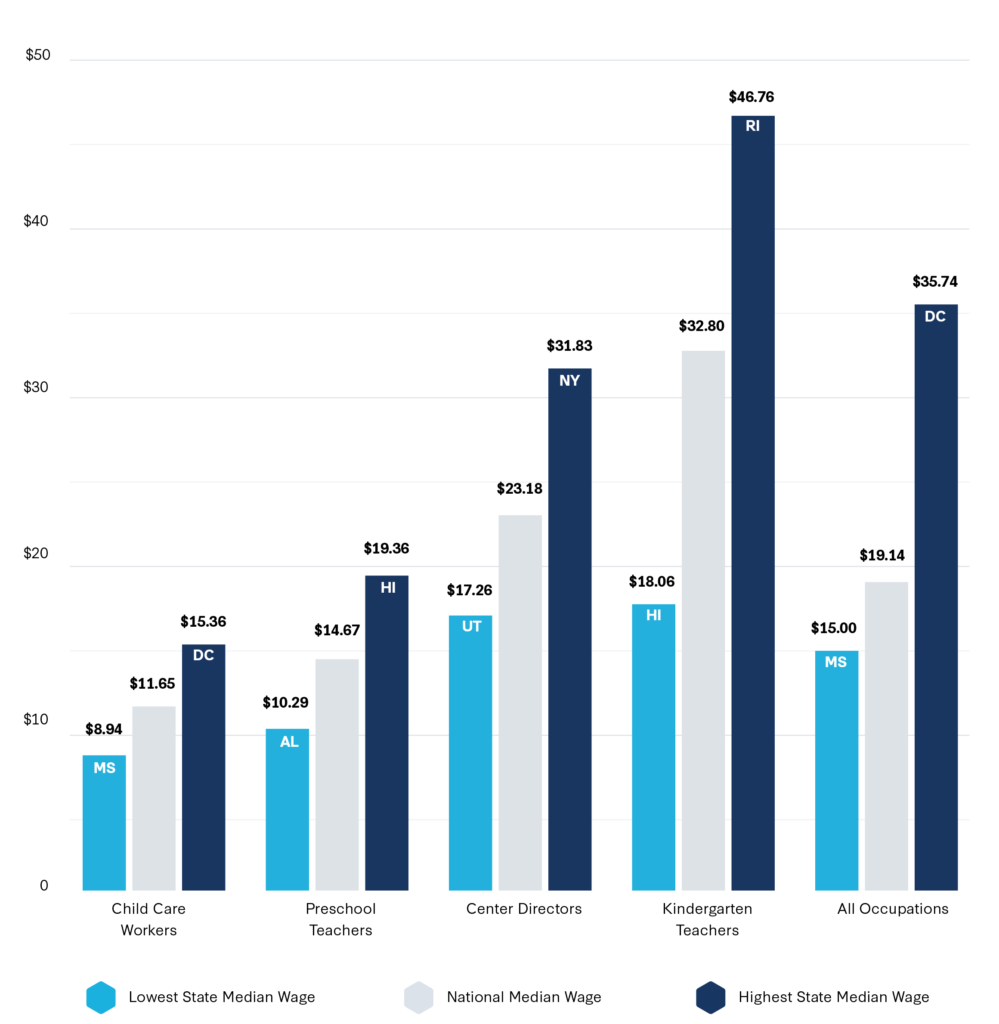

Early Educator Wages Remain Low Across States, 2019

Child care workers make up the majority of the ECE workforce in most states (see Appendix Table 2.1 for individual state data), yet across states, median wages for child care workers are lower than for other ECE occupations (preschool teachers and center directors), as well as overall median wages for all occupations. In 2019, median hourly wages for child care workers ranged from $8.94 in Mississippi to $15.36 in the District of Columbia (see Figure 2.4), but in more than one-half of states (28), the median wage for child care workers was less than $11 per hour (see Appendix Table 2.4 for data for all states). In all but two states (Maine and Vermont), child care workers earned less than two-thirds of the median wage for all occupations in the state — a common threshold for classifying work as “low wage” (see Appendix Table 2.8).10Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) (2015). “Wage levels” (indicator). Retrieved from: http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/employment/wage-levels/indicator/english_0a1c27bc-en.Child care workers in Maine and Vermont earned only marginally above that threshold at 70 percent of the median wage for all occupations in the state.

Preschool teachers — across settings, not only those in publicly funded pre-K, where earnings are higher — fare only somewhat better and usually make up a smaller proportion of the ECE workforce across states. Preschool teacher hourly wages in 2019 ranged from $10.29 in Alabama to $19.36 in Hawaii (see Figure 2.4). The median wage for preschool teachers fell below the state median wage for all occupations across all states. In six states (Alabama, Alaska, Delaware, North Dakota, Rhode Island, Wisconsin) and the District of Columbia, preschool teachers would be considered “low wage,” earning less than two-thirds of the median wage for all occupations in the state (see Appendix Table 2.5 for data for all states).

The median wage for preschool teachers fell below the state median wage for all occupations across all states.

Hourly wages for both child care workers and preschool teachers are lower than for kindergarten teachers, which ranged from $18.06 in Hawaii to $46.76 in Rhode Island (see Figure 2.4 and see also Appendix Table 2.7 for all states). Center directors’ hourly wages also varied substantially by state, ranging from $17.26 in Utah to $31.83 in New York. In all states but two (North Dakota and Utah), center directors earned more than the overall median wage in the state (see Appendix Table 2.6).

“All staff in our program are significantly underpaid compared to what they could make for comparable positions in other school settings. Many of us stay anyway, because we love the vision and overall climate/work environment, but I recognize that economic stresses can take a toll on the energy I bring to the classroom each day.”

New York11Quote from CSCCE survey of teachers. For more information about the study, see Whitebook, M., Schlieber, M., Hankey, A., Austin, L.J.E., & Philipp, G. (2018). Teachers’ Voices: Work Environment Conditions That Impact Teacher Practice and Program Quality — New York. Berkeley, CA: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved from https://cscce.berkeley.edu/teachers-voices-new-york-2018/.

FIGURE 2.4

Median Wages, by Occupation & in Lowest/Highest Earning States, Not Adjusted for Cost of Living, 2019

Note: All teacher estimates exclude special education teachers. Hourly wages for preschool teachers in schools only, kindergarten teachers, and elementary school teachers were calculated by dividing the annual salary by 40 hours per week, 10 months per year, in order to take into account standard school schedules. All other occupations assume 40 hours per week, 12 months per year.

Little Change in Early Educator Wages Across States, 2017-2019

Child Care Workers

Median child care worker wages increased in 34 states between 2017 and 2019, after adjusting for inflation (see Figure 2.5); a similar number was reported in the 2018 Index for the period 2015-2017 (33 states). Fewer than half of those 34 states saw increases of greater than 5 percent: 12 states saw increases of between 5 and 10 percent, and only three states (Hawaii, Maine, and Washington) saw increases between 10 and 15 percent. Overall, these increases translate into small raises for child care workers, given their low starting wages. Even the largest percent increase, 13 percent in Washington State, only represents a change from $12.89 (in 2019 dollars) to $14.57 in 2019, a gain of approximately $3,500 in yearly income that leaves child care workers still earning less than $15 per hour.

Of the remaining 17 states, nearly all saw a reduction of less than 10 percent, although two states (Missouri, West Virginia) saw no change between 2017 and 2019.

Figure 2.5

State Map of Percent Change in Child Care Worker Median Wage, 2017-2019

Preschool Teachers

Median wages increased in fewer states for preschool teachers than for child care workers. After adjusting for inflation, 24 states saw an increase between 2017 and 2019 (see Figure 2.6), a smaller number than reported in the 2018 Index for the period 2015-2017 (32 states). Fewer than one-half of those 24 states saw increases of greater than 5 percent: 10 states saw increases of between 5 and 10 percent, and four states (Iowa, Maine, Minnesota, Missouri) saw increases of between 10 and 15 percent. The largest percent increase, 12 percent in Minnesota, represents a change from $15.62 (in 2019 dollars) to $17.46 in 2019, a gain of about $3,800 in yearly income.

While five states (Georgia, Illinois, New Hampshire, Oregon, Wisconsin) saw no change in median preschool teacher wages during the period 2017-2019, 21 states and the District of Columbia saw decreases. A similar trend was reported in the 2018 Index during 2015-2017, when more than one-half of states saw a decrease in preschool teacher wages. In some cases, these decreases are substantial: during 2017-2019, in six states (Alabama, Kentucky, Louisiana, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Wyoming), wages decreased by at least 10 percent. At one extreme, Louisiana preschool teacher wages dropped by 28 percent, from $17.86 in 2017 (in 2019 dollars) to $12.91 in 2019, a difference of more than $10,000 in annual wages. The reasons for these reductions are unclear and may be due to shifts in the dataset from year to year, rather than because of an underlying economic or policy change.

Figure 2.6

State Map of Percent Change in Preschool Teacher Median Wage, 2017-2019

Center Directors

As with preschool teachers, wages for center directors increased in 24 states between 2017 and 2019 (see Figure 2.7), the same number as reported in the 2018 Index for the period 2015-2017 (24 states). Fewer than one-half of those 24 states saw increases of greater than 5 percent between 2017 and 2019: six states (Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Nevada, New Mexico, Tennessee) saw increases of 10 percent or greater, and 10 states saw increases of between 5 and 10 percent (Alabama, Connecticut, Iowa, Maine, Montana, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Virginia, Wisconsin). Only in two states (New Mexico and Nevada) was there an increase of 15 percent or more — Nevada saw an increase of 31 percent, becoming the second-highest median wage in the nation for center directors at $29.35 (ranking sixth when adjusted for cost of living).

While two states (Arizona, New York) saw no change in center director wages between 2017 and 2019, nearly one-half of states saw decreases (24). In eight cases, these reductions were substantial: wages decreased by 10 percent or more in Alaska, Arkansas, Florida, Kentucky, Oregon, Rhode Island, Utah, and Wyoming. Kentucky saw the most precipitous drop: center director wages dropped by 21 percent, from $21.77 (in 2019 dollars) to $17.30 in 2019.

Figure 2.7

State Map of Percent Change in Center Director Median Wage, 2017-2019

Further details on changes in wages for early educators as well as kindergarten and elementary school teachers are available in Appendix Tables 2.10 and 2.11.

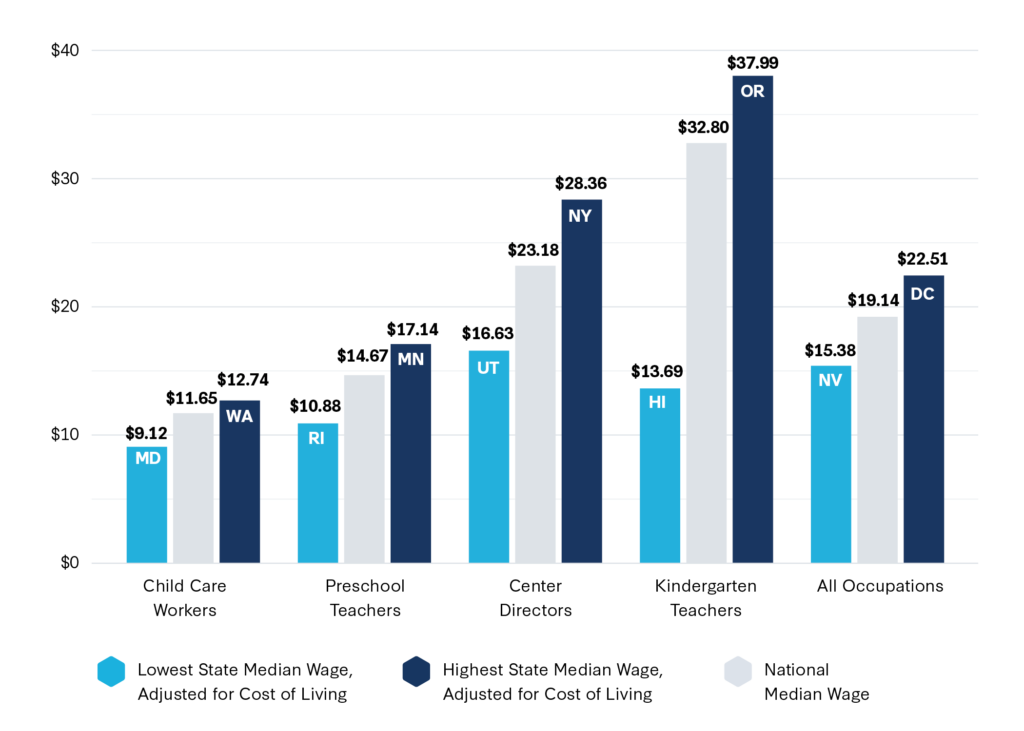

Early Educator Wages Across States, Adjusted for Cost of Living

In a state with a low cost of living, $10 has more purchasing power than in a state with a high cost of living. Adjusting median wages to account for the cost of living in each state reveals a very different picture in terms of which states have the highest and lowest median wages for early childhood occupations. For child care workers, the highest adjusted wage is $12.74, paid in Washington State, and Maryland is lowest with an adjusted $9.12 (as an illustration, see Figure 2.8). Similarly, for preschool teachers, the highest wage is found in Minnesota, with an adjusted wage of $17.14, and Rhode Island falls last with an adjusted $10.88 (see Appendix Table 2.2, for all occupations). When kindergarten teacher wages are adjusted for the cost of living, Oregon leads with an adjusted $37.99 hourly wage, and Hawaii is last with an adjusted $13.69. For directors, the highest wage comes from New York with a $28.36 hourly adjusted wage, and Utah is last with a $16.63 hourly wage.

Figure 2.8

Median Wages, by Occupation & in Lowest/Highest Earning States, Adjusted for Cost of Living, 2019

Note: All teacher estimates exclude special education teachers. Hourly wages for preschool teachers in schools only, kindergarten teachers, and elementary school teachers were calculated by dividing the annual salary by 40 hours per week, 10 months per year, in order to take into account standard school schedules. All other occupations assume 40 hours per week, 12 months per year.

Early Educator Wages Are Not Livable Wages in Most States

At a minimum, everyone working with young children should earn at least a livable wage, which would be higher than current minimum wage levels.12McLean, C., Whitebook, M., & Roh, E. (2019) From Unlivable Wages to Just Pay for Early Educators. Berkeley, CA: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved from https://cscce.berkeley.edu/from-unlivable-wages-to-just-pay-for-early-educators/. Although what counts as “livable” is not universally agreed upon, standards do exist and are calculated based on the ability to afford basic necessities in a given community. For example, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Living Wage Calculator “draws upon geographically specific expenditure data related to a family’s likely minimum food, child care, health insurance, housing, transportation, and other basic necessities (e.g., clothing, personal care items, etc.) costs […] and the rough effects of income and payroll taxes to determine the minimum employment earnings necessary to meet a family’s basic needs while also maintaining self-sufficiency.”13Glasmeier, A. (2020). About the Living Wage Calculator. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved from http://livingwage.mit.edu/pages/about.

Living wages vary by household type as well as by state, given differences in the cost of living. For a single adult with no children, median child care worker wages in only 10 states (Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, Maine, Minnesota, Nebraska, North Dakota, Vermont, Washington, and Wyoming) are equivalent to or more than the living wage for that state. This number is an increase from the five states (Arizona, Colorado, Vermont, Washington, and Wyoming) that met this threshold in the 2018 Index.14Whitebook, M., McLean, C., Austin, L.J.E., & Edwards, B. (2018). Early Childhood Workforce Index – 2018. Berkeley, CA: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved from https://cscce.berkeley.edu/early-childhood-workforce-2018-index/. However, in the majority of states, wages fall short of the living wage for a single adult, from just under the living wage (short by $0.13) in Montana to as much as $3.39 less per hour in Hawaii. The median gap between child care wage and livable wage threshold across all states is -$0.96, meaning around one-half of the states are at least $1.00 per hour short of the threshold for a living wage for a single adult. These findings translate into unlivable wages for child care workers in most states (see Figure 2.9).

In only three states (Maine, Vermont, Washington) and the District of Columbia does the median child care worker wage even meet one-half (50-54 percent) of a living wage for a single adult with one child.

For a single adult with one child, median child care worker wages do not meet a living wage in any state. In only three states (Maine, Vermont, Washington) and the District of Columbia does the median child care worker wage even meet one-half (50-54 percent) of a living wage for a single adult with one child (see Appendix Table 2.9). This represents a small but notable change from no states meeting even half of a living wage for a single adult with one child, as reported in the 2018 Index.15Whitebook, M., McLean, C., Austin, L.J.E., & Edwards, B. (2018). Early Childhood Workforce Index – 2018. Berkeley, CA: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved from https://cscce.berkeley.edu/early-childhood-workforce-2018-index/. Yet, child care wages in all states fall quite far below a livable wage for an adult with one child, meaning child care workers as well as their families are suffering from inadequate, poverty-level wages.

These data mirror teacher reports of struggling to afford basic necessities outlined earlier in this report, as well as the quickly deteriorating financial circumstances of many ECE programs as a result of the pandemic. They dramatically demonstrate the need for wage standards in ECE and public funding to ensure that increased costs are not passed on to parents in the form of additional fees.

Figure 2.9

Gap Between Child Care Worker Median Wage & Living Wage for One Adult With No Children, by State

Early Educators Face a Pay Penalty for Working With Children 0-5

Even when early educators hold a bachelor’s degree, there is a pay penalty for working with children from birth to age five, compared to working with school-age children in the K-8 system, in all states.16Data for early educators include American Community Survey respondents in the child care workers occupational category and in the preschool and kindergarten teachers occupational category with public school workers excluded (as a proxy for excluding kindergarten teachers). See Gould, E., Whitebook, M., Mokhiber, Z., & Austin, L.J.E. (2020). Financing Early Educator Quality: A Values-Based Budget for Every State. Berkeley, CA: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved from https://cscce.berkeley.edu/financing-early-educator-quality-a-values-based-budget-for-every-state/. In Florida, which has the smallest gap, early educators with a bachelor’s degree are paid 2.9 percent less than their colleagues in the K-8 system, and in New Mexico, which has the largest gap, educators are paid 50.6 percent less (see Figure 2.10).

The low wages endured by early educators for working with our country’s youngest children translate into high levels of poverty, ranging from 10.9 percent in Virginia to 34.4 percent in Florida. Meanwhile, poverty rates for K-8 teachers range from 0.8 percent in Virginia to 5.9 percent in Florida. (see Figure 2.11 and Appendix Table 2.12).

Figure 2.10

Pay Penalty for Early Educators With Bachelor’s Degrees, by State, 2019

Figure 2.11

Poverty Rates for Early Educators & K-8 Teachers

Continue reading →

Next Chapter: State Policies to Improve Early Childhood Educator Jobs