Work Environment Standards

What Are Work Environment Standards?

Work environment standards ensure safe, supportive workplace conditions that promote professional growth and teaching practice. Standards should be coupled with funding for ECE programs to provide safe and supportive work environments for early educators.

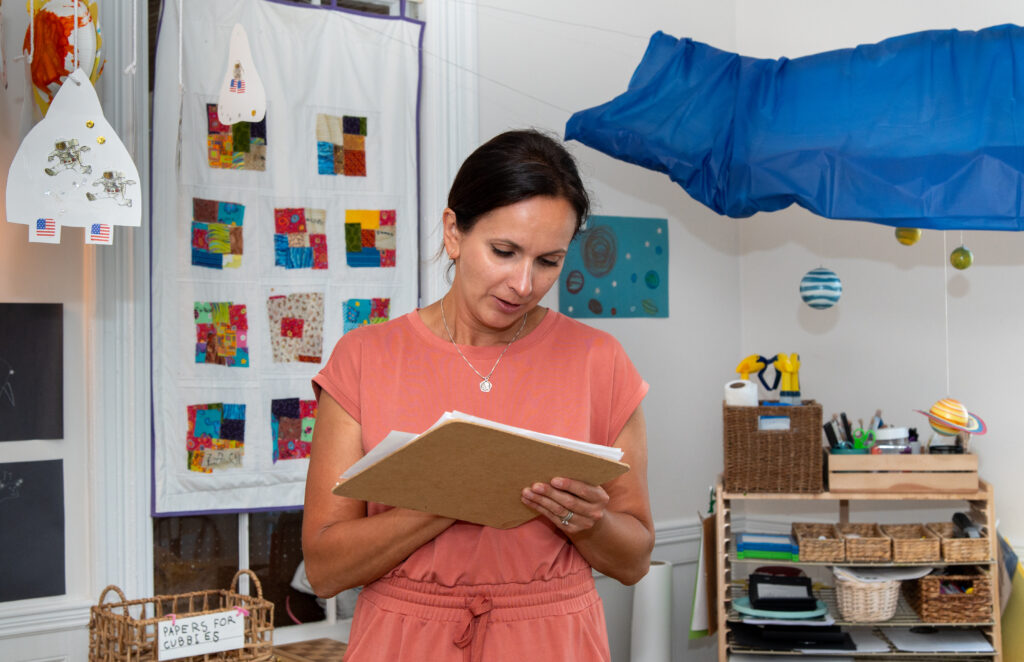

Early childhood educators need safe, supportive work environments. Such environments include appropriate pay, benefits (health insurance, retirement, and paid time off), and opportunities for ongoing learning. In addition, supports that enable good teaching practices include sufficient staffing, paid non-child contact time for completion of professional responsibilities and reflection with colleagues, and opportunities to provide input into decisions that affect programs, classrooms, and teaching practices. Supportive work environments are also an effective tool for retention. Early educators who feel better supported by their program’s policies and practices are more likely to want to stay in their program.1 Schlieber, M., Knight, J., Adejumo, T., Copeman Petig, A., Valencia López, E., & Pufall Jones, E. (2023). Early Educator Voices: Oregon. Work Environment Conditions That Impact Early Educator Practice and Program Quality. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. https://cscce.berkeley.edu/publications/report/educator-voices-oregon/; Schlieber, M., Copeman Petig, A., Valencia López, E., & Pufall Jones, E. (2023). Early Educator Voices in Florida: Flagler and Volusia Counties. Work Environment Conditions That Impact Early Educator Practice and Program Quality. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. https://cscce.berkeley.edu/publications/report/early-educator-voices-in-florida-counties/.

Too often, early educators work in settings that undermine their physical and financial well-being and lack supports to engage in effective teaching.2 Cassidy, D.J., King, E.K., Wang, Y.C., Lower, J.K., & Kintner-Duffy, V.L. (2017). Teacher work environments are toddler learning environments. Early Childhood Development and Care, 187(11), 1666–1678. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2016.1180516; Institute of Medicine & National Research Council. (2015). Transforming the Workforce for Children Birth Through Age 8: A Unifying Foundation. The National Academies Press. https://www.nap. edu/catalog/19401/transforming-the workforce-for-children-birth-through-age-8-a; Whitebook, M., Phillips, D. & Howes, C. (2014). Worthy Work, STILL Unlivable Wages: The Early Childhood Workforce in 25 years after the National Childcare Staffing Study. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. https://cscce.berkeley.edu/publications/report/worthy-work-still-unlivable-wages/. A 2023 CSCCE study of teacher work environments in Oregon found that early educators reported conditions that threaten their health and safety, specifically not being able to take their paid sick leave or breaks during the workday (although required by law to do so).3 Schlieber, M., Knight, J., Adejumo, T., Copeman Petig, A., Valencia López, E., & Pufall Jones, E. (2023). Early Educator Voices: Oregon. Work Environment Conditions That Impact Early Educator Practice and Program Quality. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. https://cscce.berkeley.edu/publications/report/educator-voices-oregon/ Although educators across settings face insufficient staffing support and lack of paid time to engage in planning and professional responsibilities, these challenges can be even more acute for educators in home-based settings, who often work alone or with only a single assistant.4Schlieber, M., Knight, J., Adejumo, T., Copeman Petig, A., Valencia López, E., & Pufall Jones, E. (2023). Early Educator Voices: Oregon. Work Environment Conditions That Impact Early Educator Practice and Program Quality. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. https://cscce.berkeley.edu/publications/report/educator-voices-oregon/; Schlieber, M., Copeman Petig, A., Valencia López, E., & Pufall Jones, E. (2023). Early Educator Voices in Florida: Flagler and Volusia Counties. Work Environment Conditions That Impact Early Educator Practice and Program Quality. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. https://cscce.berkeley.edu/publications/report/early-educator-voices-in-florida-counties/. These conditions, coupled with low pay, undermine early educators’ well-being and exacerbate stress and turnover.5 Kwon, K-A., Ford, T.G., Salvatore, A.L., Randall, K., Jeon, L., Malek-Lasater, A., Ellis, N., Kile, M.S., Horm, D.M., Kim, S.G., & Han, M. (2022, November 10). Neglected Elements of a High-Quality Early Childhood Workforce: Whole Teacher Well-Being and Working Conditions. Early Childhood Education, Journal, 50, 157–168. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-020-01124-7; Smith, S., & Lawrence, S. (2019, March). Associations with Children’s Experience, Outcomes, and Workplace Conditions: A Research-to-Policy Brief. Child Care and Early Education Research Connections. https://www.nccp.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/text_1224.pdf.

“We are spread so thin. Even when sick, I feel guilt, and I’m not sure who will cover the classroom—our work environments need help. Ever since COVID, we’ve been spread very thin. This puts a lot of stress on you—it’s a lot.”

Early educator voices could greatly contribute to policy decisions promoting supportive work environments. Most early educators lack a formal or organized mechanism for expressing concerns and influencing decisions about their working conditions and how their ECE programs are financed and structured. Overall, unionization rates among early educators are much lower than among K-12 teachers.7 As of 2023, the union membership rate was 7 percent of child care workers, compared with 13 percent for preschool/kindergarten teachers and 45 percent of elementary and middle school teachers, see Hirsch, B., Macpherson, D., & Even, W. (2024, January 18). Union Membership and Coverage Database from the CPS. Union Membership, Coverage, Density, and Employment by Occupation, 2023. https://unionstats.com/. However, collective bargaining has been an effective strategy for improving supports for some home-based providers in 11 states.8 Collins, C., & Gomez, A.L. (2023, April). Unionizing Home-Based Providers to Help Address the Child Care Crisis. The Center for Law and Social Policy. https://www.clasp.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/4.3.2023_Unionizing-Home-Based-Providers-to-Address-the-Child-Care-Crisis.pdf. The union contracts include increased wages, health benefits, paid time off, supplies, and paid training and professional development. In Connecticut, early educators also won a seat on the cabinet that oversees early care and education.9 Collins, C., & Gomez, A.L. (2023, April). Unionizing Home-Based Providers to Help Address the Child Care Crisis. The Center for Law and Social Policy. https://www.clasp.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/4.3.2023_Unionizing-Home-Based-Providers-to-Address-the-Child-Care-Crisis.pdf. Most recently, California became the first state in the nation to offer a retirement fund for family child care providers through a contract negotiated by Child Care Providers United (CCPU).10 Jones Lawrence, B. (2023, September 14). Child Care Contract: A Step Toward Equity and a Promise for Systemic Change. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. https://cscce.berkeley.edu/blog/child-care-contract-a-step-toward-equity-and-a-promise-for-systemic-change/. These efforts demonstrate the need for an organized voice from early educators to effect true and lasting change.

The importance of early educator working conditions and well-being is increasingly being recognized. For example, the federal Office of Head Start (OHS) finalized rule changes for Head Start-funded ECE programs that will require increased pay, benefits like health insurance and paid time off, breaks, and access to mental health supports.11 Head Start, ECLKC. (2024, February). Final Rule Supporting the Head Start Workforce and Consistent Quality Programming. Head Start Policy and Regulations. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families. https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/policy/article/final-rule-supporting-head-start-workforce-consistent-quality-programming. These requirements offer a national model for improving educator working conditions, but are limited to educators working in federally funded Head Start programs. And without appropriate increases to Head Start funding, ECE program leaders will struggle to implement the changes.

States Turn to Model Work Standards to Guide Improvements in Working Conditions

More than two decades ago, early educators in center- and home-based programs led an effort to articulate standards for their work environments to support their teaching practice. Updated and re-released in 2019, the Model Work Standards for Centers and Homes continue to provide a vision for ensuring ECE teachers’ rights and needs are met.1Center for the Study of Child Care Employment (CSCCE) & American Federation of Teachers Educational Foundation (AFTEF). (2019). Model Work Standards for Teaching Staff in Center-Based Child Care. https://cscce.berkeley.edu/creating-better-child-care-jobs-model-work-standards/; Center for the Study of Child Care Employment (CSCCE) & American Federation of Teachers Educational Foundation (AFTEF). (2019). Model Work Standards for Early Educators in Family Child Care. https://cscce.berkeley.edu/creating-better-child-care-jobs-model-work-standards/.

In recent years, several states have turned to the Model Work Standards to guide their thinking and planning about what early educator work environments should look like.2Each of these examples were identified through state administrator responses to CSCCE’s 2024 Early Childhood Workforce Index survey.

- In Minnesota, state leaders are referring to the Model Work Standards as a resource as they revise the standards and indicators used in their quality rating and improvement system (QRIS).

- Indiana Association for the Education of Young Children (AEYC) utilizes these standards to inform their workforce technical assistance.

- Leaders in Washington and Wisconsin have used the Model Work Standards as guidelines and inputs into their strategic planning.

Other than the recently proposed changes to Head Start regulations, there are still no federal standards for early educator work environments.12 Other federal ECE initiatives, like the Department of Defense child care program, do not include explicit standards for work environments for providers that receive their funds nor are such standards required by the federal Child Care Development Block Grant. For information on voluntary national accreditation standards, see Whitebook, M., McLean, C., Austin, L.J.E., & Edwards, B. (2018). Early Childhood Workforce Index – 2018. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. http://cscce.berkeley.edu/topic/early-childhood-workforce-index/2018/. In their absence, individual states must take the lead. Unfortunately, state-level quality improvement initiatives have consistently missed the mark by focusing on ECE workforce education and training. Few initiatives focus on improving work environments and educator well-being. Even state-level quality rating and improvement systems (QRIS), which have become the dominant strategy for assessing and improving quality in ECE programs, too often fail to address the importance of teacher work environments.

The effectiveness of QRIS as mechanisms to improve quality in an equitable fashion has been questioned, including by our own organization.13 Jenkins, J., Duer, J., & Connors, M. (2021). Who participates in quality rating and improvement systems? Early Childhood Research Quarterly 54(1), 219–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2020.09.005; Lieberman, A. (2017, June 2). Even With More Research, Many Q’s Remain about QRIS. New America. https://www.newamerica.org/education-policy/edcentral/even-more-research-many-qs-remain-about-qris/. Many states tie public child care funding to quality ratings, even though these funds are already typically too low to support high-quality services. ECE programs that have less private funding, such as those serving racially and economically marginalized communities, are further disadvantaged in accessing public funding, making it even more difficult to improve quality.14 Hollett, K.B., & Frankenberg, E. (2022). A critical analysis of racial disparities in ECE subsidyfunding. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 30(14). https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.30.7003; Jenkins, J., Duer, J., & Connors, M. (2021). Who participates in quality rating and improvement systems? Early Childhood Research Quarterly 54(1), 219–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2020.09.005; Lieberman, A. (2017, June 2). Even With More Research, Many Q’s Remain about QRIS. New America. https://www.newamerica.org/education-policy/edcentral/even-more-research-many-qs-remain-about-qris/.

Despite our concerns about QRIS, we continue to assess whether states include work environment standards for center- and home-based ECE programs in their QRIS because these systems remain the primary way that states aim to improve quality. As more states recognize the limitations of QRIS and pursue alternatives, future editions of the Index will document those forward-looking strategies. For example, Massachusetts paused its QRIS while the state works to develop a continuous quality improvement system and revises child care licensing requirements.15 Department of Early Education and Care. (2024). Promoting High Quality Early Education and Care. Massachusetts Executive Office of Education. https://www.mass.gov/info-details/promoting-high-quality-early-education-and-care. Massachusetts also incorporated quality add-on funding into the state’s base child care subsidy rates and no longer requires ECE programs to have a QRIS rating in order to receive that level of funding. Both these strategies indicate bold steps toward a system in which ECE program leaders understand how to build supportive work environments and have the public funding they need to do so (see Public Funding).

Policy Solutions to Improve Working Conditions

Advance the emotional and physical health and well-being of educators in the work environment by ensuring appropriate compensation and access to health care, including mental health supports.

Adopt system-level workplace standards, such as guidance on appropriate levels of paid planning time. Paid planning time is necessary for educators to engage in professional practice to support children’s learning and to alleviate conditions that cause educator stress.

- Use existing models, such as the International Labor Organization Policy Guidelines and the U.S.-based Model Work Standards for Centers and Homes.3International Labour Organization (ILO). (2013). ILO policy guidelines on the promotion of decent work for early childhood education personnel. Meeting of Experts on Policy Guidelines on the Promotion of Decent Work for Early Childhood Education Personnel, Geneva, 12–15 November 2013/International Labour Office, Sectoral Activities Department. https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_dialogue/@sector/documents/normativeinstrument/wcms_236528.pdf; Center for the Study of Child Care Employment (CSCCE) & American Federation of Teachers Educational Foundation (AFTEF). (2019). Model Work Standards for Teaching Staff in Center-Based Child Care. https://cscce.berkeley.edu/creating-better-child-care-jobs-model-work-standards/; Center for the Study of Child Care Employment (CSCCE) & American Federation of Teachers Educational Foundation (AFTEF). (2019). Model Work Standards for Early Educators in Family Child Care. https://cscce.berkeley.edu/creating-better-child-care-jobs-model-work-standards/.

- Develop intentional mechanisms to engage educators as partners in the process of developing workplace standards to ensure these standards reflect their needs and experiences.

- In partnership with educators, assess and update quality, licensing, and competency requirements to include workplace standards, with the goal of implementing equitable standards across programs.

- Recognize and remedy the racial and class inequities embedded in QRIS by providing sufficient public funding for all programs to meet work environment standards.

- Provide ongoing financial resources and technical assistance to enable programs to implement standards in a reasonable period of time and to sustain compliance with these standards over time.

- Require all programs that receive public funding to complete training on work environment standards and to implement an annual self-assessment and improvement plan.

Collect data on a regular basis from early educators to assess how they experience the standards in their work environments and communicate how changes will be made to address their feedback and concerns.

Establish the right of all early educators to organize and/or join a union. Unions provide a safe channel to report and remedy unsafe or problem conditions in the work environment.

Ensure protections are in place for workers who report workplace or regulatory violations (e.g.,California’s whistleblowing law).4California Legislation Information (n.d.). Health and Safety Code Division 2, Chapter 3.4, Article 3 Remedies for Employer Discrimination. https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/codes_displayText.xhtml?lawCode=HSC&division=2.&title=&part=&chapter=3.4.&article=3. As part of onboarding and annual protocols, inform educators about their rights, including state laws around occupational health and safety, and the reporting process.

State Progress on Work Environments

- Stalled: 27 states

- Edging Forward: 11 states

- Making Headway: 3 states

- Not Available: 2 states

- Not Applicable: 8 states

Overall, there has been little progress on work environment standards across states since the 2020 Index. The majority of states still do not include key work environment standards in their QRIS indicators. Only a few states changed their status, either progressing or regressing (see Figure 3.2.1).

- Three states (New York, Washington, and Wisconsin) were assessed as making headway, and 11 states were edging forward.

- States that took a step forward: Only one state (Washington) advanced from edging forward in 2020 to making headway in 2024, with the addition of a salary schedule and benefits standard for center- and home-based programs. Two states (Oregon, and Texas) and the District of Columbia moved from stalled to edging forward in 2024. Alabama was newly assessed as edging forward due to new data availability.

- States that took a step back: Delaware and Maine moved from edging forward to stalled, and Vermont went from making headway to stalled. Massachusetts, previously assessed as making headway, is no longer assessed, as Massachusetts has paused its QRIS.16 Department of Early Education and Care. (2024). Promoting High Quality Early Education and Care. Massachusetts Executive Office of Education. https://www.mass.gov/info-details/promoting-high-quality-early-education-and-care.

To assess state progress, the Index examines three indicators from QRIS work environment standards for center- and/or home-based programs. They are: 1) standards related to paid time for professional development; 2) paid planning/preparation time; and 3) salary schedule/benefits. While we recognize that work environments include many elements, these key areas can be compared and assessed across all 50 states and the District of Columbia.

Our assessment of state progress on each of the three indicators found very few changes, mostly for center-based programs.

- There was no marked change in the number of states that include standards related to a salary schedule/benefits for center- and home-based settings.

- For center-based programs, there was a net decrease (-1 state) in states with standards related to paid time for professional development and a net decrease (-2 states) in states with standards related to paid planning/preparation time.

- For home-based programs, there was a net increase (+1 state) in states with standards related to paid time for professional development and no marked change in states with standards related to paid planning/preparation time.

Some changes to state progress in work environments were a result of adding or removing standards between 2020 and 2024, while other changes may be due to changes in the availability of data from the QRIS Compendium.17 Build Initiative & Child Trends. (2024). Quality Compendium. https://qualitycompendium.org/.

Table 3.2.1.

Key to State Progress on Work Environment Standards

Figure 3.2.1.

Map of State Progress on Work Environment Standards, 2024

Figure 3.2.2.

Number of States Making Progress on Work Environment Standards, 2020 and 2024

Figure 3.2.3.

Number of States Making Progress on Work Environment Standards per Indicator, 2020 and 2024

State Progress on Work Environment Standards: Indicators

Indicator 1: Does a state’s QRIS include standards for paid professional development time for center- and home-based programs?

Rationale: Paid professional development enables educators to engage in reflection and collaboration with peers, which is necessary for the ongoing development of teaching practice, while receiving compensation for their time and contributions.

Current Status Across States:

- Fourteen states include paid professional development time as a quality benchmark for center-based programs.

- The District of Columbia and New York include paid professional development time as a quality benchmark for home-based programs.

Change Over Time: Since 2020, there was a net decrease of one in the number of states that include paid professional development time standards for center-based programs in their QRIS.

- Two states (Arkansas, Oregon) and the District of Columbia added standards.

- Three states removed standards (Nebraska, North Dakota, and Vermont).

- Massachusetts could no longer be assessed due to the pause in their QRIS.

For home-based settings, there was a net increase of one state including paid professional development time in their QRIS: while Vermont removed standards, the District of Columbia and New York added standards to their QRIS.

Indicator 2: Does a state’s QRIS include standards for paid planning and/or preparation time for center- and home-based programs?

Rationale: Paid time for teachers to plan or prepare for children’s activities is essential to a high-quality service, but it is not guaranteed for early educators, many of whom must plan while simultaneously caring for children or during unpaid hours.

Current Status Across States:

- Fourteen states include paid planning and/or preparation time as a quality benchmark for center-based programs.

- Eight states include paid planning and/or preparation time as a quality benchmark for home-based programs.

Change Over Time: Since 2020, there was a net decrease of two states that removed paid planning and/or preparation standards for center-based programs in their QRIS.

- Six states (Arkansas, Delaware, Indiana, New Mexico, South Carolina, and Vermont) removed standards.

- Three states (Nebraska, Oklahoma, Texas) and the District of Columbia added standards.

For home-based programs, the overall number of states meeting this indicator did not change.

- Two states (Colorado, Texas) and the District of Columbia added standards to their QRIS.

- Three states (Delaware, New Mexico, and Vermont) removed standards.

For both centers and home-based programs, Massachusetts could no longer be assessed as its QRIS is on pause, reducing the overall number of states that meet the above indicator. However, Alabama was able to be assessed for the first time due to new data availability, which increased the overall number of states that meet the above indicator.

Indicator 3: Does a state’s QRIS include standards for salary scales and/or benefits for center- and home-based programs?

Rationale: QRIS could be an opportunity to signal that—just like education levels—compensation and retention are important markers of quality, but not all QRIS include standards for salary scales or benefit options (e.g., health insurance, paid sick leave, family leave, vacation/holidays) as part of their ratings. Additionally, even when QRIS include such standards, they may still lack guidelines for programs about what is appropriate (e.g., salary scales that begin at a living wage rather than the minimum wage).

Current Status Across States:

- Twenty-one states include standards for salary scales and/or benefit options for center-based programs.

- Eleven states include standards for salary scales and/or benefit options for home-based programs.

Change Over Time: Since 2020, there was no change in the overall number of states meeting this indicator for both center- and home-based settings. However, there were changes to the states that added or removed these standards from their QRIS.

For center-based programs, three states (Oklahoma, Texas, and Washington) added standards to their QRIS, while three states (Delaware, Nevada, and Vermont) removed standards.

Similarly, for home-based programs, two states (Texas and Washington) added standards in their QRIS, and two states (Delaware and Maine) removed standards.

For both centers and home-based programs, Massachusetts could no longer be assessed as its QRIS is on pause, reducing the overall number of states that meet the above indicator. However, Alabama was able to be assessed for the first time due to new data availability, which increased the overall number of states that meet the above indicator.

Table 3.2.2.

Progress on Work Environment Standards, By State and Territory, 2024

Continue reading →

Next Section: Compensation & Financial Relief