Homepage – Early Childhood Workforce Index 2024

Early Childhood Workforce Index

The Early Childhood Workforce Index provides a state-by-state look at policies and conditions affecting the early care and education workforce. This major report has tracked state progress since 2016.

2024 Report

The fourth edition of the Index continues to track state policies in essential areas like workforce qualifications, work environments, and early educator compensation. The 2024 report provides updated policy recommendations and spotlights states that are improving ECE workforce policies.

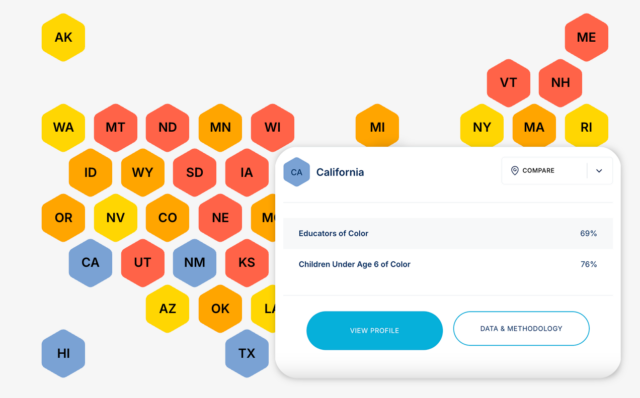

State Explorer

The Early Childhood Workforce Index includes a profile for every state and the District of Columbia with detailed information on early educator wages and state policies. Compare states and territories using the interactive mapping tool.

Supported By

The 2024 Early Childhood Workforce Index is generously supported by the Heising-Simons Foundation, the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, the Bainum Family Foundation, the Alliance for Early Success, the W. Clement & Jessie V. Stone Foundation, and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation.

FAQs

- What is the purpose of the Early Childhood Workforce Index?

Nationwide, the teachers and caregivers who make up the early childhood workforce are struggling to get by on low wages and face insufficient workplace supports. Without transforming policies that shape how we prepare, support, and pay early educators, the 21st-century goal of quality early learning opportunities for all children will remain elusive.

The Early Childhood Workforce Index provides a state-by-state look at policies and conditions affecting the early care and education workforce. It aims to spur advocates and policymakers to take action toward meaningful ECE policy reform. Repeated editions of the Index make it possible to identify trends and track progress in the states over time.

- What are the five essential policy areas of the Index?

- Qualifications and educational supports: Policies and pathways that provide consistent standards and support for educators to achieve higher education.

- Work environment standards: Standards and funding to make sure ECE programs can provide safe and supportive work environments for early educators.

- Compensation and financial relief strategies: Initiatives and investments to ensure compensation is commensurate with that of a skilled professional, accounting for the educator’s qualifications, expertise, and experience.

- Workforce data: State-level collection and use of key data on the size, characteristics, and working conditions of the ECE workforce.

- Public funding: Public investment in the ECE workforce and broader ECE system.

- How often is the Index updated?

In previous years, the Index was updated biennially. After the 2020 Index, CSCCE focused on actionable efforts to increase compensation across states and became a partner in the National ECE Workforce Center, launched in 2023. With the publication of the 2024 edition, the Index will return to a biennial schedule. The next edition of the Index will be released in 2026.

- Who is included in the early childhood workforce?

A wide variety of terms are used to refer to the early care and education sector and its workforce. They depend on the age of children served (e.g., infants and toddlers, preschool-age children) and the location of the service (centers, schools, or homes), as well as funding streams, job roles, and data sources. We use the terms “early childhood workforce,” “early care and education (ECE) workforce,” or “early educators” to encompass all those who work directly with young children for pay in early care and education settings in roles focused on teaching and caregiving. We use more specific labels, such as “Head Start teacher” or “home-based provider” when we are referring to a particular type of setting. In some cases, we are limited by the labels used in a particular data source. For example, we may refer to “childcare workers” and “preschool teachers” because we relied on data specific to subcategories of the workforce as defined and labeled by the Standard Occupational Classification of the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

- What is the source of the ECE workforce wage data?

The 2024 edition of the Early Childhood Workforce Index uses wage data from the 2022 American Community Survey (ACS), a departure from previous editions that reported data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics (OEWS). The most recent year for which detailed state-by-state data are available from the ACS is 2022. Using the ACS is an intentional change to provide more inclusive wage estimates for the ECE workforce by using a data source that includes home-based providers. More recent data from OEWS 2023 are available, but this data source excludes self-employed workers like family child care providers. The OEWS also does not allow us to study the ECE workforce as a whole, since we are unable to parse or combine categories of workers. For instance, the national OEWS estimates for median wages in 2023 were $14.60 for child care workers, $17.85 for preschool teachers, and $26.10 for directors or administrators.

For more detailed information on data sources, see Appendix 1: Data Sources and Methodology.

- What is the source of the ECE workforce policy data?

There is no comprehensive data source for tracking the early childhood workforce in its entirety over time throughout the United States. Nor is there a single source of comprehensive information about early childhood workforce policies across all 50 states and the District of Columbia. As a result, the 2024 Index compiles information from a variety of sources:

- Information for the majority of the policy indicators for each state and the District of Columbia comes from CSCCE’s original data collection processes through a cross-state review of ECE agency websites and a state survey. The Index state survey was sent to one or more representatives from each state (child care licensing/subsidy administrators, QRIS administrators, registry administrators, etc.) to verify and supplement previously collected information.

- We also use databases and reports specific to the early childhood field that cover all 50 states, such as the National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER) State of Preschool Yearbook and the Quality Rating and Improvement Systems Compendium;

- CSCCE partnered with the National Workforce Registry Alliance to analyze data from their landscape scan of workforce registries across the country.

- CSCCE also reviewed and analyzed data contributed by the T.E.A.C.H. Early Childhood® National Center and the Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP).

For more detailed information on data sources, see Appendix 1: Data Sources & Methodology.

- What’s the difference between child care workers and preschool teachers?

Child care workers and preschool teachers are occupational groupings defined by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Standard Occupational Classification, which is used to classify all occupations in the United States for the purposes of federal data collection. These categorizations also appear in the American Community Survey (ACS), which we use to analyze the early care and education workforce in the 2024 Index.

The BLS defines “childcare workers” as those who “attend to children at schools, businesses, private households, and childcare institutions” and “perform a variety of tasks, such as dressing, feeding, bathing, and overseeing play,” while “preschool teachers” are those who “instruct preschool children in activities designed to promote social, physical, and intellectual growth needed for primary school in preschool, day care center, or other child development facility.” In the ACS, workers are classified as one or another, depending on how they self-describe their job title. For instance, if a person uses the word “teacher” when naming their occupation within early care and education, they are highly likely to be counted in the “preschool teacher” occupation, whereas using the word “provider” would lead them to be counted as a “childcare worker.”1U.S. Census Bureau. (2024, September 12). Industry and Occupation Indexes. https://www.census.gov/topics/employment/industry-occupation/guidance/indexes.html.

These definitions do not adequately reflect distinctions in settings and roles among early educators, and as a result, there have been calls to revise the classifications. For more information, see: Workgroup on the Early Childhood Workforce and Professional Development (2016). Proposed Revisions to the Definitions for the Early Childhood Workforce in the Standard Occupational Classification: White paper commissioned by the Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (OPRE Report 2016-45). Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- How is the Index making an impact?

The Index has raised awareness of the conditions facing early educators. The report fills the state and national data gap on the workforce, making it indispensable to policymakers, news outlets, and the early care and education community. The first Index in 2016 drove almost all of the media coverage about early educators that year, including in the New York Times and on PBS NewsHour, according to media analysis by the David and Lucile Packard Foundation. The 2020 Index was cited by more than 450 news articles, posts, and clips in 2021 and continues to serve as a reference for outlets from NPR to the Los Angeles Times.

Index data and policy recommendations are reflected in elements of the American Families Plan, Build Back Better legislation, and official guidance on how to use federal dollars for ECE workforce compensation. The Index likewise accounts for one third of the references in the grant announcement of the National Early Care and Education Workforce Center.

As state and federal advocacy groups become increasingly aware of the need to focus more on educators’ needs, in addition to those of children and families, they regularly cite the Index as a resource in state plans. Examples include:

- The rationale for Washington, D.C.’s historic Early Childhood Educator Pay Equity Fund.

- A report to the Washington state legislature on improving pay for early educators;

- Recommendations by a state-level advisory group in Minnesota for supporting the ECE workforce;

- A report by the California Assembly Blue Ribbon Commission on Early Childhood Education; and

- Colorado’s 2020 plan for the early childhood workforce.

See additional examples of how educators, advocates, and legislators have used the Early Childhood Workforce Index.

- What are the key findings from the 2024 Index?

Early Educators Are Highly Skilled, Diverse

Early educators are skilled, experienced professionals, many of whom have 16 or more years of experience and hold college degrees. Early educators are racially, ethnically, and linguistically diverse, like the children they care for and educate. Depending on the setting, 40 to 56 percent of early educators are women of color.

Economic Insecurity Remains Rampant

The work of teaching and caring for young children is highly skilled and complex, yet early educators are paid some of the lowest wages in the United States.

- Nationally, early educators are paid a median wage of $13.07 per hour, much less than hourly earnings for elementary and middle school teachers ($31.80) or the U.S. workforce across occupations ($22.92).

- 97 percent of other occupations are paid more than early educators.

- Wages vary somewhat by location, ranging from $10.60 in Louisiana to $18.23 in the District of Columbia. Yet early educator wages do not meet a living wage for a single adult with no children in any state, even though many early educators are themselves also parents, with children at home.

- 43 percent of early educator families must rely on public safety net programs like Medicaid and food stamps in order to get by and still struggle with financial insecurity and economic stress.

Pay Inequity Is Entrenched in the System

As difficult as it is for anyone to be an early educator in America, conditions are even more harmful for Black and Latina women, who are paid thousands of dollars less than their peers each year, even when holding equivalent educational degrees.

There are also pay disparities linked to program funding source and the ages of children in their care: an early educator working in a child care program, a Head Start-funded program, or a public pre-K program is likely to earn different amounts for doing the same work.

New Policies Support Early Educators, But Lack of Sustained Public Funding Hinders Progress

Federal ARPA and other COVID-19 relief funding provided a lifeline to state and program leaders in the context of the pandemic. The majority of states used pandemic relief funds to fund workforce initiatives that increased wages, provided wage supplements, expanded scholarships, and provided personal protective equipment and mental health supports, among other uses.

COVID-19 relief funding was never sufficient nor intended to sustain the ECE system or the workforce over the long term. State and local leaders have the power and authority to advance policies to support the ECE workforce, with and without federal funding.

- Some states are pointing the way toward a public system of early care and education for all children from birth to age five with substantial new state investments, such as Vermont’s payroll tax or New Mexico’s Early Childhood Education and Care Fund.

- The District of Columbia is using a local wealth tax to fund grants to ECE programs to meet minimum salaries aligned with the District’s public school salary scale.

For a more detailed summary of findings, see the Executive Summary.

- What are your recommendations for improving early childhood workforce policy?

The Index outlines a number of concrete steps that policymakers and other stakeholders can take at the state and federal levels to ensure a high-quality, affordable early care and education system. For a complete list of action items, see the Policy Toolkit.

Recommendation #1: Ensure early educators have a seat at the table in decision making that affects them.

- Include early educator representatives on all ECE advisory councils, boards, committees, and task forces.

- Support collective bargaining by early educators.

Recommendation #2: Offer all members of the current and future ECE workforce opportunities and support to acquire education and training at no personal financial cost.

Recommendation #3: Adopt system-level workplace standards, such as guidance on appropriate levels of paid time off for vacation and sick leave, paid planning and professional development time, and mental health and teaching supports.

Recommendation #4: Articulate compensation standards for early educators across all settings.

- Establish a wage floor so that, at a minimum, no one working in early care and education earns less than a regionally assessed living wage.

- Create a wage/salary scale that sets minimum standards for pay, accounting for job role, experience, and education levels.

Recommendation #5: Dedicate ongoing funding to producing, analyzing, and reporting high-quality data on workforce characteristics and conditions that can be used to inform and assess policies.

Recommendation #6: Increase public investment in the early childhood workforce.

- Include target standards for salaries, benefits, and professional work supports like paid planning time in cost models to identify the true cost of providing high-quality care.

- Dedicate state and local revenue to early care and education, like New Mexico’s Early Childhood Education and Care Fund, and consider dedicating funding to workforce needs, like the District of Columbia’s Pay Equity Fund.

- Use grants and contracts to provide stable funding to all ECE programs to cover core personnel costs like salaries, benefits, and other supports for professional working conditions.

- How do I find information on my state?

For a full breakdown of how your state measures up on each indicator, see our State Profiles.

- How does my state compare to other states?

The Early Childhood Workforce Index does not formally rank states because even those states making the most progress still have much work to do to improve early childhood jobs.

We group states into three broad categories based on how well they are doing along a series of measurable indicators for state policies specific to the early childhood field as well as broader policies intended to support working families.

- Red represents stalled: the state has made limited or no progress.

- Yellow represents edging forward: the state has made partial progress.

- Green represents making headway: the state is taking action and advancing promising policies.

See our State Explorer to compare your state to other states for each policy area.

- How can I request technical assistance support?

Please email Dr. Caitlin McLean, Director of Multistate and International Programs, for additional information.

- Does the Index provide information on the U.S. territories?

Yes, please see Early Educators in the U.S. Territories.

- Does the Index provide information on Tribal early care and education?

Yes, please see Tribal Early Care and Education.

- Does the Index provide information at the city or county level?

No. The Index is a state-by-state assessment of early childhood employment conditions and policies. It does not systematically track or report policies and practices at the local level.

- When can I download the report?

The full report, individual chapters, and state profiles will be available for download in early 2025.

- How do I cite the Index?

2024

McLean, C., Austin, L.J.E., Powell, A., Jaggi, S., Kim, Y., Knight, J., Muñoz, S., & Schlieber, M. (2024). Early Childhood Workforce Index – 2024. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. https://cscce.berkeley.edu/workforce-index-2024/.

2020

McLean, C., Austin, L.J.E., Whitebook, M., Olson, K.L., & Edwards, B. (2020). Early Childhood Workforce Index – 2020. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. https://cscce.berkeley.edu/workforce-index-2020/.

2018

Whitebook, M., McLean, C., Austin, L.J.E., & Edwards, B. (2018). Early Childhood Workforce Index – 2018. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. http://cscce.berkeley.edu/topic/early-childhood-workforce-index/2018/.

2016

Whitebook, M., McLean, C., & Austin, L.J.E. (2016). Early Childhood Workforce Index – 2016. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. https://cscce.berkeley.edu/early-childhood-workforce-2016-index/.