Key Findings

Early childhood educators—largely women and often women of color—nurture and facilitate learning for millions of young children every day. Despite their important work, complex skills, and considerable experience, early educators’ working conditions currently undermine their well-being and create devastating financial insecurity well into retirement age. In turn, these conditions lead to high turnover rates and teacher staffing shortages, which limit the availability of care for families.

How early educators are treated affects how our children learn. Ensuring educators’ working conditions and well-being enables them to thrive as teachers and caregivers during the most important years of a child’s life.

The essential role early childhood educators play was recognized in policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, especially the major increases in federal funding through the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) in March of 2021. This pandemic relief funding provided a crucial lifeline to state and program leaders in the context of the pandemic, when thousands of programs closed and jobs were lost. This historic funding also demonstrated an opportunity and several solutions: many state and program leaders chose to invest in the working conditions and well-being of the early care and education (ECE) workforce.

But now we are at a crossroads: the last ARPA funding dedicated to child care expired at the end of September 2024, broader pandemic relief funding is dwindling, and elections across the country will bring new leadership in 2025 and beyond.

The need to invest in the early care and education workforce continues, as too many early educators still struggle in poverty and programs continue to face high turnover and difficulty recruiting and retaining staff. COVID-19 relief funding was never sufficient nor was it intended to sustain the ECE system or the workforce over the long term.

Early educators’ poor working conditions are not inevitable, but a product of policy choices that have consistently let down the women who are doing this essential work. It’s time for the system to change. State and local leaders have the power and authority to advance policies to support the ECE workforce, with and without federal funding.

Making early care and education an attractive field now and in the future means fundamentally reshaping early childhood jobs to provide fair compensation and supportive working conditions. Not only will this change make a meaningful difference to the financial lives of current and future early educators, but it will be a major step toward recognizing the value of historically feminized work and establishing a racially and gender-just society.

“No matter where we are located, we all have the same needs: respect, pay, and support.”

What’s New in the 2024 Early Childhood Workforce Index

Since 2016, the biennial Early Childhood Workforce Index has tracked the status of ECE workforce policies in order to identify promising practices for improving early educator jobs and changes over time. This fourth edition includes new analyses as well as updated policy recommendations. Highlights include:

- A data snapshot of the national early care and education workforce;

- 50-state data on early childhood educator wages and poverty rates, using a new methodology that includes self-employed early childhood educators like family child care providers;

- State-level data on early childhood educator households’ use of public safety net programs;

- Detailed tables on state workforce policies and initiatives, especially for Qualifications and Educational Supports, Compensation and Financial Relief, and Workforce Data;

- New data on the use of ARPA and other COVID-19 relief funding for the ECE workforce;

- A new Tribal profile in addition to a profile of the U.S. territories and individual profiles of every state and the District of Columbia.

To view state assessments in previous editions of the Early Childhood Workforce Index, see:

Early Educators Are Highly Skilled, Diverse

Every day, in homes and centers across the country, about 2.2 million adults, mostly women, are paid to care for and educate more than 9.7 million children between birth and age five. Regardless of setting or role, these early educators are responsible for safeguarding and facilitating the development and learning of our nation’s youngest children.

We use “early childhood workforce,” “early care and education workforce,” or “early educators” to encompass all those who work directly with children from birth to age five in roles focused on teaching and caregiving in group early care and education settings, whether they work in schools, centers, or homes.

The ECE workforce is made up of skilled, experienced professionals. Many early educators have 16 or more years of experience2 Center for the Study of Child Care Employment. (2022). Early Educator Engagement and Empowerment (E4) Toolkit. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. https://cscce.berkeley.edu/publications/report/early-educator-engagement-and-empowerment-e4-toolkit/. and hold college degrees. Nationwide, close to one third (30 percent) of center-based teaching staff and one fifth (20 percent) of home-based listed and unlisted providers hold a bachelor’s degree or higher (see Figure 1.1). Another 18 percent of the ECE workforce in center-based settings, 20 percent in listed home-based settings, and about 10 percent of unlisted home-based providers hold an associate degree.

Figure 1.1.

Education of the Early Care and Education Workforce, By Setting, 2019

Early educators are racially, ethnically, and linguistically diverse, like the children they educate and care for: 40 to 56 percent of early educators are women of color, depending on the setting. Yet the ECE system in the United States reflects and reinforces gender, class, and racial inequities that are woven throughout U.S. institutions and culture. Early educators of color occupy a disproportionate share of the lowest-paying jobs in the field, a result of historical and systemic barriers to accessing education and job opportunities.3 Lloyd, C.M., Carlson, J., Barnett, H., Shaw, S., & Logan, D. (2021). Mary Pauper: A Historical Exploration of Early Care and Education Compensation, Policy, and Solutions. Child Trends. https://earlyedcollaborative.org/what-we-do/mary-pauper/.

For further details and visual summaries of the data, see About the Early Childhood Workforce.

Economic Insecurity Remains Rampant

The historical and pervasive undervaluing of labor performed by women, especially women of color, has created one of the most underpaid workforces in the United States. The work of teaching and caring for young children is highly skilled and complex, yet employment in early care and education has largely failed to generate wages that allow early educators to meet their basic needs, regardless of years of tenure in the field or educational attainment.

- Nationally, early educators are paid a median wage of $13.07 per hour, much less than hourly earnings for elementary and middle school teachers ($31.80) or the U.S. workforce across occupations ($22.92) (see Figure 1.2).

- 97 percent of other occupations are paid more than early educators.

- Wages vary somewhat by location, ranging from $10.60 in Louisiana to $18.23 in the District of Columbia. Yet early educator wages do not meet a living wage for a single adult with no children in any state, even though many early educators are themselves parents with children at home (see Figure 1.2).

- Early educators’ low wages result in poverty rates that are 5.7 times higher than poverty rates for elementary and middle school teachers: 13.1 percent of early educators earn below the federal poverty line, compared to 2.3 percent of elementary and middle school teachers.

- Early educators frequently lack access to benefits like health insurance and retirement plans through their workplace.

- 43 percent of early educator families must rely on public safety net programs like Medicaid and food stamps in order to get by (see Figure 1.3). They struggle with financial insecurity and economic stress. Low wages subsidize ECE programs and parent tuition fees, but it comes at a cost: taxpayers invest more than $4.7 billion per year in public safety net expenses for early educators’ families to offset their insufficient earnings.

Figure 1.2.

Median Hourly Wages, By Occupation, 2022

Figure 1.3.

Early Educator Families Participating in Public Safety Net Programs, 2021

Pay Inequity Is Entrenched in the System

It is difficult for anyone to be an early educator in America, but for Black and Latina women, the conditions are even more harmful. Early educators of color are paid thousands of dollars less than their White peers each year, even when they hold equivalent educational degrees.

A White early educator earns around $8,000 more per year than a Black early educator.

There are also pay disparities linked to the funding source and the ages of children served: early educators working in a child care program, a Head Start-funded program, or a public pre-K program are likely to earn different amounts for doing the same work.

- Educators working in centers with public funding are paid higher wages than those employed in centers without public funding. Among center-based teaching staff who hold a bachelor’s degree or higher, those working in school-sponsored pre-K programs were paid more than $20,000 more per year compared to educators working in centers without public funding.

- A pay penalty for working with younger children persists. Among center-based teaching staff with a bachelor’s degree or higher working in ECE centers that are not school-sponsored, early educators working only with infants and toddlers are paid about $8,000 less per year than those working exclusively with children age three to five, not yet in kindergarten.

Wage Growth Lags Behind Fast Food and Retail Wages

Early educators’ wages have risen by 4.6 percent nationally in recent years, after adjusting for inflation (see Figure 1.4). This increase is less than inflation-adjusted wage growth for the U.S. workforce as a whole (4.9 percent), as well as fast food workers (5.2 percent) and retail workers (6.8 percent).

Across the states, wage growth varied substantially:

- Nine states as well as the District of Columbia saw an increase in ECE wages of more than 10 percent, outpacing wage growth across their respective states as a whole. The highest increases were in the District of Columbia (27.1 percent) and Utah (16.8 percent), both places where there were recent, targeted investments in ECE compensation.

- 10 states saw early educator wages fall while wages across all occupations rose.

Figure 1.4.

Percent Change in National Median Wage, By Occupation, 2019-2022

For further details and visual summaries of the data, see Early Educator Pay & Economic Insecurity.

New Policies Support Early Educators, Lack of Sustained Public Funding Hinders Progress

Federal ARPA and other COVID-19 relief funding provided a lifeline to state and program leaders in the context of the pandemic that initially forced many ECE programs to close and resulted in the loss of thousands of child care jobs. This major influx of federal funding demonstrated that given the funds and the flexibility, state and program leaders will choose to invest in the ECE workforce.

The majority of states used pandemic relief funds for workforce initiatives that increased wages, provided wage supplements, expanded scholarships, and provided personal protective equipment and mental health supports, among other uses. Here are just a few examples:

- Utah offered ECE programs additional funding tied to their stabilization grants, but only if programs paid at least half of their staff a minimum of $15 per hour. It’s possible that this initiative contributed to the almost 17-percent inflation-adjusted wage increase CSCCE observed in Utah between 2019 and 2022 (see Appendix Table 2.5). However, this initiative ended when their pandemic relief funding was spent.

- Kentucky used stabilization grants to incentivize wage increases by offering higher payments to ECE programs that paid higher wages.

- Ohio used pandemic relief funds to eliminate a waitlist for educators to participate in POWER Ohio, a wage stipend and retention program.

- Mississippi provided scholarships, bonus pay incentives, additional professional development, and mental health supports.

ARPA investments signal a major shift in state leaders prioritizing the use of public dollars to fund critical compensation and financial relief initiatives. Without further public funding, higher wages and financial relief are most at risk. More than 45 compensation and financial relief initiatives have already ended, aligning with the expiration of ARPA child care stabilization funding in September 2023 (see Appendix Table 3.8). The expiration of ARPA discretionary CCDF funding in September 2024 threatens the continued existence of many additional compensation and financial relief initiatives.

COVID-19 relief funding was never sufficient nor intended to sustain the ECE system or the workforce over the long term. Many states have voiced the need for additional, sustained funding and warned of the risks to gains made for the workforce if further funding is not secured. Yet the majority of states do not have state-level funding or other plans in place to address the September 2024 funding cliff. As of June 2024, only eleven states (Alaska, California, Illinois, Kentucky, Maine, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Vermont, Washington) and the District of Columbia had been identified as making significant state investments to fill the gaps left in child care funding when federal dollars from the American Rescue Plan Act expired.4 The White House, Council of Economic Advisers. (2024, June 27). Impacts of the Expiration of Federal Child Care Stabilization Funding and the Mitigating Effects of State-Level Stopgap Funding. https://www.whitehouse.gov/cea/written-materials/2024/06/27/impacts-of-the-expiration-of-federal-child-care-stabilization-funding-and-the-mitigating-effects-of-state-level-stopgap-funding/.

In the absence of major new federal investments that are required to make sustained, transformative change across the country, states must rise to the challenge to find solutions of their own. State and local leaders have the power and authority to advance policies to support the ECE workforce, with and without federal funding.

- Some states are pointing the way toward a public system of early care and education for all children birth to five with substantial new state investments, such as Vermont’s payroll tax or New Mexico’s Early Childhood Education and Care Fund.

- The District of Columbia is using a local wealth tax to fund grants to ECE programs to meet minimum salaries aligned with the District’s public school salary scale.

- Minnesota and Illinois are investing state funds to advance early educator compensation, continuing grants to ECE programs that were first begun using federal pandemic relief funds.

- California became the first state to fund a retirement program for early educators as a result of collective bargaining with the Child Care Providers United union representing home-based providers.

Although there has been meaningful progress in recent years, all states have far to go to achieve a system in which all early educators are paid enough to thrive, regardless of setting, funding source, or the age of the children they work with. To make sustainable progress on compensation for all early educators and to make teaching young children an attractive career, there must be a reckoning with the inadequacy of current levels of public funding at local, state, and federal levels. Historic levels of federal funding through ARPA demonstrated that transformative reforms can be made, but they will require increased and sustained investment.

Advancing Early Childhood Educator Workforce Policies: The Index Framework

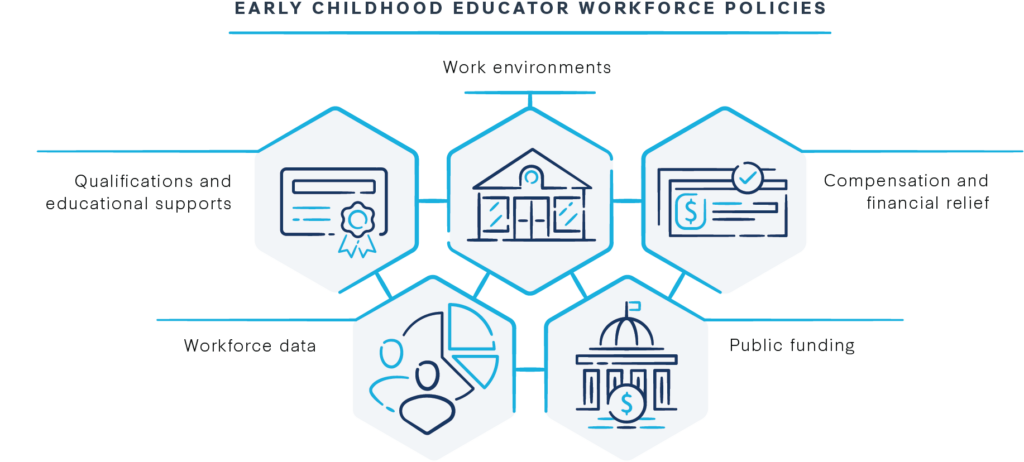

Across five essential policy areas, the Early Childhood Workforce Index examines state-level policies that can spur progress on the status and well-being of early childhood educators:

- Qualifications and educational supports: Policies and pathways that provide consistent standards and support for educators to achieve higher education.

- Work environment standards: Standards to hold ECE programs accountable for providing safe and supportive work environments for early educators.

- Compensation and financial relief strategies: Initiatives and investments to ensure compensation equal to the value of early educators’ work.

- Workforce data: State-level collection of important data on the size, characteristics, and working conditions of the ECE workforce.

- Public funding: Public investment in the ECE workforce and broader ECE system.

Figure 1.5.

Five Policy Areas to Improve Early Childhood Educator Jobs

To summarize overall state action in each policy area, states are assigned to one of three tiers based on their performance on measurable policy indicators:

- Stalled: The state is making limited or no progress;

- Edging Forward: The state is making partial progress; or

- Making Headway: The state is taking action and advancing promising policies.

Despite recent advances, the majority of states continue to be appraised as stalled or edging forward across early childhood educator workforce policy categories related to qualifications, work environments, compensation, and public funding (see Figure 1.6).

Figure 1.6.

Number of States Making Progress Across Five Policy Areas

For further details, including a table of each state’s progress, changes in state policies since 2020, and visual summaries of the data per policy area, see State Policies to Improve Early Childhood Educator Jobs.

For more information about each of the indicators and the data sources used, see Appendix 1: Data Sources & Methodology.

Continue reading →

Next Section: Policy Recommendations