State Policies Overview

Download State Policies OverviewThe Need for ECE System Reform

A functional early care and education system is one that is equitable and meets the needs of children, parents, and educators, simultaneously. The reliance on the private market for fundamental education and care needs ensures that the ECE system in the United States has never risen to the level of “good” but has long operated from a place of scarcity, failing to meet the needs of children, parents, and educators. The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic has only exacerbated these circumstances.

The early care and education system wasn’t working even before COVID-19.

Parents persistently struggle to access early childhood services due to limited supply and the costs involved in providing services.1Economic Policy Institute (2020). The Cost of Child Care in Alabama. Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute. Retrieved from https://www.epi.org/child-care-costs-in-the-united-states/. Families with low incomes face particular difficulty accessing services, especially high-quality care that is more costly to operate. Additionally, many families eligible for public support to pay for ECE do not actually receive it because the system is chronically underfunded and oversubscribed.2Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) (2016). Estimates of Child Care Eligibility and Receipt. Washington, DC: Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved from: https://aspe.hhs.gov/estimates-child-care-eligibility-and-receipt; Schmit, S., & Walker, C. (2016). Disparate Access. Washington, DC: Center for Law and Social Policy. Retrieved from https://www.clasp.org/sites/default/files/public/resources-and-publications/publication-1/Disparate-Access.pdf. These supply and affordability challenges were severe prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and have only become more dire,3Child Care Aware of America (2020). Picking Up the Pieces: Building a Better Child Care System Post COVID-19. Arlington, VA: Child Care Aware of America. Retrieved from https://info.childcareaware.org/hubfs/Picking%20Up%20The%20Pieces%20%E2%80%94%20Building%20A%20Better%20Child%20Care%20System%20Post%20COVID%2019.pdf. with serious consequences for parents, especially mothers, who are struggling to work due to lack of child care access.4Heggeness, M.L., & Field, J.M. (2020). Working Moms Bear Brunt of Home Schooling While Working During COVID-19. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2020/08/parents-juggle-work-and-child-care-during-pandemic.html.

Children have access to quality ECE services according to what their parents can afford, not based on their individual educational and developmental needs. As a result, children face inequitable access to services driven by the income of their families,5Schmit & Walker, 2016. Disparate Access. Washington, DC: Center for Law and Social Policy. Retrieved from https://www.clasp.org/sites/default/files/public/resources-and-publications/publication-1/Disparate-Access.pdf; Friedman-Krauss, A., & Barnett, S. (2020). Special Report: Access to High-Quality Early Education and Racial Equity. New Brunswick, NJ: National Institute for Early Education Research. Retrieved from: http://nieer.org/policy-issue/special-report-access-to-high-quality-early-education-and-racial-equity perpetuating wider systems of social and economic disadvantage in education and later life.

Early educators consistently endure poor pay and inadequate working conditions, with circumstances even worse for educators of color, who experience wage gaps and unequal pay for equal work in an already severely underpaid sector.6Austin, L.J.E., Edwards, B., Chavez, R., & Whitebook, M. (2019). Racial Wage Gaps in Early Education Employment. Berkeley, CA: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved from https://cscce.berkeley.edu/racial-wage-gaps-in-early-education-employment/. The COVID-19 pandemic has worsened the economic and health insecurities faced by the ECE workforce, with mass closures and layoffs for many educators, and unsafe working conditions for others.7Whitebook, M., Austin, L.J.E., & Williams, A. Is child care safe when school isn’t? Ask an early educator. Berkeley, CA: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved from: https://cscce.berkeley.edu/is-child-care-safe-when-school-isnt-ask-an-early-educator/; Child Care Aware of America (2020). Picking Up the Pieces: Building a Better Child Care System Post COVID-19. Arlington, VA: Child Care Aware of America. Retrieved from https://info. childcareaware.org/hubfs/Picking%20Up%20The%20Pieces%20%E2%80%94%20Building%20A%20Better%20Child%20 Care%20System%20Post%20COVID%2019.pdf.

The COVID-19 pandemic may force a reckoning with these perennial issues. However, to date, relief efforts by the federal government have fallen far short of what is needed to stabilize, much less reform, an ECE system that has never worked for parents, children, or educators. Left largely on their own, many states and localities have been stymied in their efforts to adequately address the crisis. Publicly funded programs and the educators who work in them have been better able to weather the crisis by channeling emergency funds through existing funding mechanisms.8Bassok, D., Michie, M., Cubides-Mateus, D.M., Doromal, J.B., & Kiscaden, S. (2020). The Divergent Experiences of Early Educators in Schools and Child Care Centers during COVID-19; Findings from Virginia. EdPolicyworks, University of Virginia. Retrieved from https://files.elfsight.com/storage/022b8cb9-839c-4bc2-992e-cefccb8e877e/710c4e38-4f63-41d0-b6d8-a93d766a094c.pdf. Yet, the bulk of the ECE system depends on parent fees — an unreliable revenue source in the best of times, much less in the throes of a pandemic and abrupt economic recession. The deficiencies of the existing system are both a product of and contributor to the continued lack of progress in transforming early childhood educator jobs. The ECE workforce remains poorly compensated and undervalued, despite increased recognition of their essential service since the onset of the pandemic.

“We are more educated than the general population, but we make less than someone with just a high school degree…. The market cannot sustain wages at a professional salary just because parents can’t pay it.”

Wisconsin9Quote from a virtual convening of early educators on September 19, 2020 hosted by CSCCE, “Elevating Early Educator Voices in the 2020 Early Childhood Workforce Index”.

Why the U.S. Early Care & Education System Doesn’t Work

The United States does not have a system of early care and education for children ages 0-5 in which the government at any level (federal, state, or local) assumes responsibility for ensuring that services are available, affordable, and high quality for all children and families. This shortcoming is in stark contrast to how ECE is provided in many other countries and also to how education is provided for older children in the United States, in which every child is guaranteed space in a classroom and each level of government — local, state, and federal — shares some degree of responsibility for funding schooling.

The de facto early care and education policy in this country is that it is a private, family responsibility and that ECE needs can be sufficiently satisfied by the market. Parents are typically expected to find and pay for services from an array of small, for- and nonprofit private businesses that operate in centers or homes. In very limited circumstances, services are publicly subsidized or paid in full, such as with child care vouchers, Head Start/Early Head Start, and public pre-K, with even fewer programs being directly operated by the government (for example, public school-based pre-K).

None of the limited public initiatives, neither independently nor as a group, solve the underlying problem: the market is inadequate to the task of providing a public good and ensuring that high-quality services are available for all children and families. Instead, the de facto policy and funding approach has led to a fragmented and confusing array of uncoordinated policies related to funding, eligibility, and standards, at every level of government (federal, state, and local).

Federal Government

- Funding: The federal government is the largest funder of ECE compared with state and local governments, but federal ECE programs have never been adequately funded, even to support families with low incomes. Federal funding is provided through multiple funding streams and initiatives, each serving a different purpose. The two largest are the Child Care Development Fund (CCDF), a block grant to the states to subsidize child care services for families with low incomes, and Early Head Start/Head Start, which provides early childhood services for families with low incomes and is governed by federal standards.10The Department of Health and Human Services and the Department of Education (2017). Joint Interdepartmental Review of All Early Learning Programs for Children Less Than 6 Year of Age. Washington, DC: Government Accountability Office. Retrieved from https://www2.ed.gov/about/inits/ed/earlylearning/files/gao-report-joint-interdeprtmental-review-2017.pdf.

- Eligibility for Children/Families: Family eligibility varies by the type of funding stream or initiative but is typically limited to those with the lowest incomes. For example, children whose families live below the poverty threshold are eligible for Early Head Start (for ages 0-3) or Head Start (for ages 3-5); while children under the age of 13 whose parents are working or in school and earn no more than 85 percent of the state median income (SMI) are potentially eligible for child care subsidies under CCDF, although states can and do set stricter eligibility standards.11Shulman, K. (2019). Early Progress: State Child Care Assistance Policies 2019. Washington, DC: National Women’s Law Center. Retrieved from https://nwlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/NWLC-State-Child-Care-Assistance-Policies-2019-final.pdf.

- Standards for ECE Settings: The federal government to date has done little to regulate or set standards for ECE services with the exception of Early Head Start/Head Start and Department of Defense child care services and limited requirements, such as background checks for settings receiving CCDF dollars. The federal government has never adopted a national framework for early care and education, an approach that has guided standards and reform in other countries (e.g., Australia, Norway).12Garvis, S., Phillipson, S., & Harju-Luukkainen, H. (eds.) (2018). International Perspectives on Early Childhood Education and Care Early Childhood Education in the 21st Century Vol I. New York: Routledge. Instead, regulation of the quality of ECE services is left largely to the states.

State Government

- Funding: Because state governments have typically chosen to rely on federal funds for child care services, federal infrastructure and rules often drive decisions at the state level, though state policymakers still have wide latitude to shape ECE access and standards in their state. Importantly, the acceptance of federal funding does not preclude states from investing in new or robust services, yet no state has yet determined to operate a system that is equitable and effective for all children, families, and early educators. To the extent that states have invested outside of federal programs and required matching dollars, the most common investment has been through education funding for pre-K services for some three- or (usually) four-year-olds, in line with state responsibility for education services more generally.13Friedman-Krauss, A.H., Garver, K.A., Hodges, K.S., Weisenfeld, G.G., & Gardiner, B.A. (2020). The State of Preschool 2019. State Preschool Yearbook. New Brunswick, N.J.: National Institute for Early Childhood Education Research. Retrieved from https://nieer.org/state-preschool-yearbooks/2019-2.

- Eligibility for Children/Families: Under the CCDF, states can choose to set income eligibility at up to 85 percent of the state median income (SMI), but only a handful of states actually do, with the vast majority of states setting eligibility between 40 and 60 percent of SMI.14Shulman, K. (2019). Early Progress: State Child Care Assistance Policies 2019. Washington, DC: National Women’s Law Center. Retrieved from https://nwlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/NWLC-State-Child-Care-Assistance-Policies-2019-final.pdf (2019). States also decide eligibility requirements for their pre-K programs, the majority of which set income limits for families.15Friedman-Krauss et al. (2020).

- Standards for ECE Settings: States decide whether and how to regulate the bulk of ECE services. Depending on the state, some settings may be entirely unregulated (e.g., small home-based settings or settings run by religious organizations) and may or may not be eligible for public subsidies. For pre-K, states decide whether services are delivered in public schools or community settings or both, as well as what standards programs must meet, including class sizes, ratios, teacher degree requirements, and curriculum standards. Similarly, states set requirements for child care settings via licensing rules. Compared with pre-K standards, child care licensing standards are typically more minimal and focused on health and safety rather than child development. Instead of addressing low standards by raising licensing requirements and providing the resources needed to help child care programs meet them, most states have built quality rating and improvement systems (QRIS). However, QRIS further exacerbate systemic inequities, especially between programs that rely on fees from parents with low incomes and other programs, as QRIS apply ratings to and often financially reward programs within the context of a market-based system.

City or County Government

- Funding: Like the states, city or county governments may also choose to supplement state and federal funding with local revenue sources. For example, many cities have implemented their own pre-K programs.16CityHealth and NIEER (n.d.). Pre-K in American Cities. CityHealth and the National Institute for Early Education Research. Retrieved from https://www.cityhealth.org/prek-in-american-cities/.

- Eligibility for Children/Families and Standards for ECE Settings: Local governments may also set eligibility requirements and standards specific to a program that they fund or oversee.

The consequence of the current (dis)organization of ECE is a fragmented system in which families and providers face a confusing array of eligibility and requirements for public funding. Depending on the setting (schools, centers, homes), legal status of the provider (e.g., licensed/license-exempt), and type of public funding they receive (pre-K, Early Head Start/Head Start, CCDF, or none), ECE programs are overseen by different levels of government (federal, state, local) and distinct federal or state agencies (health and human services agencies, education agencies), and therefore, they must adhere to different requirements.17Eurydice (2020). Early Childhood Education and Care. Sweden: EACEA National Policies Platform. Retrieved from https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/early-childhood-education-and-care-80_en; Smith, L., Campbell, M., Tracye, S., & Pluta-Ehlers, A. (2018). Creating an Integrated Efficient Early Care and Education System to Support Children and Families: A State-by-State Analysis. Washington, DC: Bipartisan Policy Center. Retrieved from https://bipartisanpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Creating-an-Integrated-Efficient-Early-Care-and-Education-System-to-Support-Children-and-Families-A-State-by-State-Analysis.pdf. As a result, educators lack consistent expectations for their professional practice and their rights in the workplace.18See, for example, International Labor Organization (2014) Policy Guidelines on the Promotion of Decent Work for Early Childhood Education Personnel. Geneva: International Labour Office. Retrieved from https://www.ilo.org/sector/Resources/codes-of-practice-and-guidelines/WCMS_236528/lang–en/index.htm. Similarly, children and families face widely variable eligibility for and access to publicly funded ECE programs, depending on the child’s age as well as parental work status and income. Lacking any sort of national framework for ECE, children and families across the United States have no guarantee of access to services, much less the understanding of ECE as a right, as in countries such as Sweden and Norway.19Naumann, I., McLean, C., Koslowski, A., Tisdall, K., & Lloyd, E. (2013). Early Childhood Education and Care Provision: International Review of Policy, Delivery and Funding. Edinburgh: Centre for Research on Families and Relationships and Scottish Government Social Research. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/early-childhood-education-care-provision-international-review-policy-delivery-funding/; OECD (2017). Starting Strong 2017: Key OECD Indicators on Early Childhood Education and Care. Paris: Starting Strong, OECD Publishing. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264276116-en.

What States Can Do: Seven Policy Areas to Improve Early Childhood Educator Jobs

States can enact policies that will lead to a system that provides higher quality services and more equitable treatment of educators and, consequently, more equitable services for children and families. State policymakers have many levers at their disposal to make meaningful change. States can choose to prioritize early care and education with state dollars, move beyond minimal federal requirements for funding eligibility and program standards, and invest in higher education and data collection infrastructure.

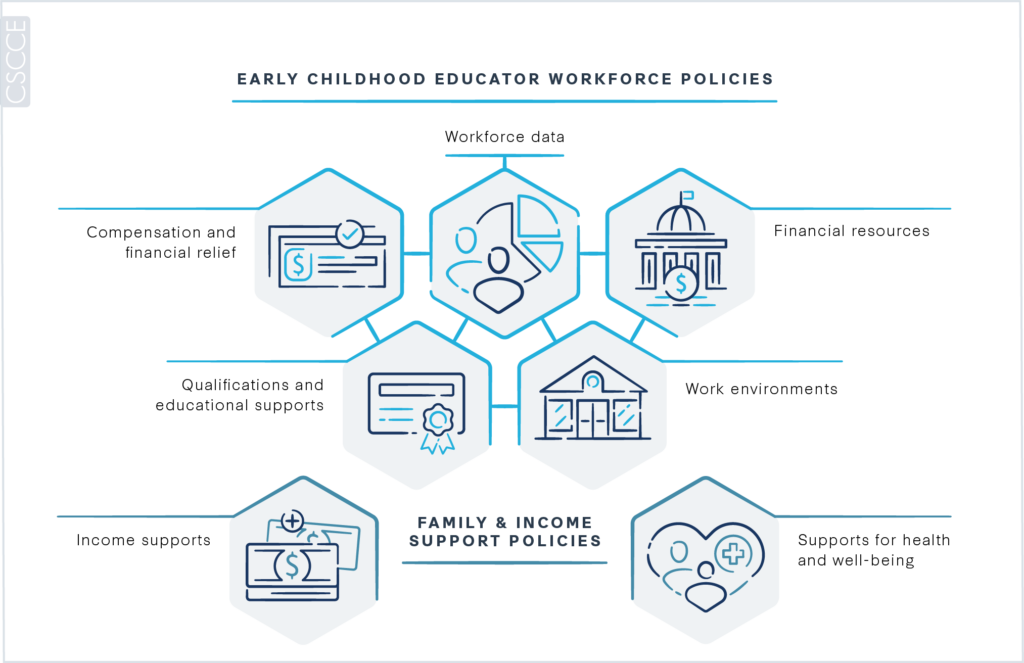

In particular, state decision makers can play a powerful role in reshaping early childhood jobs for the current and future ECE workforce. Across seven policy areas, the Early Childhood Workforce Index examines state-level policies that can spur progress on the status and well-being of early childhood educators. These seven policy areas are organized into two categories:

Figure 3.1

Seven Policy Areas to Improve Early Childhood Educator Jobs

Early Childhood Educator Workforce Policies

Legislation, regulation, and other public rule-making created and implemented with the intention of shaping and governing the early care and education workforce and system in five essential areas:

- Qualifications and educational supports: Policies and pathways that provide consistent standards and support for educators to achieve higher education.

- Work environment standards: Standards to hold ECE programs accountable for providing safe and supportive work environments for early educators.

- Compensation and financial relief strategies: Initiatives and investments to ensure compensation equal to the value of early educators’ work.

- Workforce data: State-level collection of important data on the size, characteristics, and working conditions of the ECE workforce.

- Financial resources: Public investment in the ECE workforce and broader ECE system.

Family & Income Support Policies

Broader social and labor legislation, regulation, and initiatives are designed to benefit workers and their families across occupations, not only those who work in early care and education, in two essential areas:

- Income supports and child care assistance for low-income workers and parents, including income tax credits, minimum wage legislation, and child care tax credits.

- Supports for health and well-being, which include paid sick leave, paid family leave, and access to health insurance.

Even though the ECE sector and policy leaders continue to neglect critical working conditions and compensation for early educators, movements for broader family and income supports like minimum wage legislation, paid sick days, and paid family leave legislation have been gaining momentum.

There is no single ingredient to reform. The seven policy areas in the two categories outlined above combine powerfully to benefit children, families, and early educators, as well as society as a whole.

Each of the five essential areas of early childhood workforce policy must work together to produce the guidance and resources needed to appropriately prepare, support, and compensate early educators. Adequate preparation is necessary for teachers to develop the skills required to provide high-quality learning experiences for children, while work environment standards are needed to ensure educator reflection, development, and well-being. Similarly, appropriate compensation is indispensable for attracting and retaining skilled educators. Making progress in each area of preparation, support, and compensation also requires solid foundations for policymaking: quality, comprehensive workforce data, and sufficient financial resources. A state that fails to move forward in even one of these five essential areas will struggle to advance any of the others.

Even though the ECE sector and policy leaders continue to neglect critical working conditions and compensation for early educators, movements for broader family and income supports like minimum wage legislation, paid sick days, and paid family leave legislation have been gaining momentum. These policies have increasingly been implemented across states, with real impact on early educators’ lives. Family and income support policies especially benefit low-wage workers, workers without access to benefits through their employers, and other vulnerable populations that overlap to a significant extent with the characteristics of early childhood educators. As a consequence, it is important to recognize that broader social and labor policies outside the ECE sector are important levers for transforming the quality of ECE jobs. Additionally, greater receptivity to public policies for and investment in worker and family well-being creates the conditions necessary for a broad-based coalition calling to reform the early care and education system.

How the Early Childhood Workforce Index Assesses States Across the Seven Policy Areas

In each of the seven policy areas, the Early Childhood Workforce Index assesses states based on measurable policy indicators that represent state-level opportunities to enhance the lives of the many children and adults affected by ECE employment conditions. To summarize overall state action in each policy area, states are assigned to one of three tiers, based on their performance on the indicators:

- Stalled:The state is making limited or no progress;

- Edging Forward:The state is making partial progress; or

- Making Headway:The state is taking action and advancing promising policies.

For more information about each of the indicators and the data sources used, see Appendix 1: Data Sources & Methodology.

Continue reading →

Next Section: Early Childhood Educator Workforce Policies