The 2019 update is presented by the Center for the Study of Child Care Employment and the American Federation of Teachers

Today’s early educators face growing expectations, stagnant compensation, and few resources to meet their professional needs. This is a truth I see every day in my own community, working beside early educators in Guilford County, North Carolina. Our county is not alone, however.

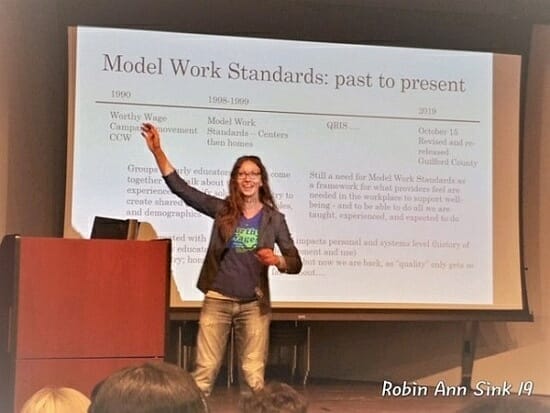

The History

Professionals providing care and education to children birth to five have historically faced inadequate working conditions. Since the late 19th century, this workforce has been composed overwhelmingly of women, a significant portion being women of color, who have subsidized the true cost of care at the expense of their own financial and professional well-being.

Organizing for change, a group of early childhood educators and care providers in the 1990s launched a national advocacy campaign fighting for “rights, raises, and respect.” The Worthy Wagers, as they were known, fought to shine a spotlight on the conditions and experiences of teachers of America’s youngest children. By 1998, during the seventh year of the campaign, this group drafted a set of seminal documents: the Model Work Standards.

The Model Work Standards

Designed to demonstrate what supportive workplace environments could look like for center-based and family child care settings, the Model Work Standards established a shared framework for quality improvement and change at the program level. While there have been strides in advancing policies and practices since the 1990s, these improvements have mostly focused on increasing the expectations of educators, and little has been done to address what educators themselves need to effectively engage in their practice.

The research clearly paints a picture of what young children require for healthy development. Yet our policy narrative still seems to dance around a simple fact: providing the quality interactions that young children need requires healthy, educated, and well-compensated teachers who enjoy supportive work environments.

Two decades of quality improvement efforts, largely absent teachers’ voices, make the Model Work Standards just as relevant today as they were in 1998. Needed now more than ever, the 2019 update for center-based teachers and family child care providers — released today by the Center for the Study of Child Care Employment and the American Federation of Teachers — has the potential to bring the needs and rights of teachers and providers back into focus.

Access them here.

The Model Work Standards in Practice Today

In my work supporting early educators and their practice, I leverage the Model Work Standards to drive conversations around change in my community. In the fall of 2017, my organization, EQuIPD, along with other groups in Guilford County, facilitated a meeting with early childhood educators, administrators, families, and community members to create a plan based on a single critical question: “What will it take for Guilford County to attract, retain, and engage a highly educated and qualified early childhood workforce?”

One teacher described how she is tired of asking for something to change because all she hears are reasons why change is not possible… repeatedly.

In these conversations, teachers explained how daily documentation and observation requirements, paired with few resources and little paid time to complete such work, impacted the care they were able to provide to children. Others described feeling unable to fully “deliver on the promise” of quality early childhood education because their programs could not retain qualified co-workers. One teacher described how she is tired of asking for something to change because all she hears are reasons why change is not possible…repeatedly. Our community came away from this event with a plan informed by the voices of more than 200 stakeholders.

Last month, at a meeting of teachers and providers in Guilford County, we previewed the updated Model Work Standards and intend to use them to build on our preceding conversations in an ongoing project in our community.

The diversity that exists among early childhood programs and stakeholder voices can make it difficult to envision exactly where a change process might begin. The Model Work Standards create an opportunity for us to collectively move from a focus on what needs changing to how we might change together, under what conditions, and what steps to consider next. The seeds for change were planted when teachers and providers came together and created the first version of the Model Work Standards. As they move back into the conversation today, we are hopeful that they will serve as a framework for our own community in Guilford County — and others, too — to bring the workforce into the center of the conversation for our future.

Our fight is not new, but the prospect of improving the working conditions and well-being of early educators makes the struggle more than worth it.

Ashley Allen is a Work Environment and Compensation Coordinator at EQuIPD, North Carolina. She leads programmatic improvement efforts and educator advocacy in the Guilford County area. Ashley is currently completing her doctoral work in educational leadership and cultural foundations at the University of North Carolina, Greensboro.