California is moving quickly to transform transitional kindergarten (TK) into a universal preschool program to be available to all four-year-olds in the state by 2025 (California Legislative Information, 2021b).

This will create the need for as many as 8,000 to 11,000 additional lead TK teachers.1In addition to these credentialed lead teachers, the expansion would require up to 26,000 aides to meet the new ratios. In child care centers and family child care homes across the state, a diverse cadre of early educators are experienced in teaching young children and well prepared to meet this demand. Yet this expansion of TK — currently planned to operate exclusively in public school settings — risks bypassing these trained professionals. Without careful attention to how TK is implemented, this model stands to bring greater instability to the early care and education (ECE) system and fuel existing racial pay gaps among the ECE workforce, ultimately undermining the state’s vision for an equitable system for children, families, and educators.

This snapshot highlights original key findings from a recent workforce survey of center-based and TK teachers and includes analysis of secondary data that are immediately relevant to the expansion of transitional kindergarten.2From October through December 2020, the Center for the Study of Child Care Employment (CSCCE) surveyed a representative sample of child care centers and licensed home-based providers for the 2020 California Early Care and Education Workforce Study, including approximately 2,000 center administrators, 2,500 center-based teachers, 3,000 family child care providers, and an exploratory sample of about 280 TK teachers. Data from the study is noted as “2020 California Early Care and Education Workforce Study” throughout the report. Additional findings from the workforce study, including results from family child care (FCC) providers and center administrators, are forthcoming.

California has a diverse, qualified, and experienced population of early educators well positioned to fill new TK jobs.

Throughout child care centers in the state, there is an experienced group of about 83,000 early childhood teachers working with children across the birth-through-preschool age continuum.3This is an initial estimate based on the 2020 California Early Care and Education Workforce Study. We derived an average number of teaching staff per center, based on center directors’ reports on the number of both teachers and assistant teachers in their centers at the time of the survey (October-December 2020). A weighted total was calculated using the total number of child care centers statewide from the California Child Care Resource & Referral Network. While this data snapshot focuses on the center-based teaching workforce, there are also thousands of FCC providers working with preschool-age children.

Racial and Ethnic Diversity

- 76% of children birth to age four (the cohort that includes TK) are children of color (KIDS COUNT Data Center, 2020).

- 70% of center-based teachers identify as people of color, which closely reflects the child population, and almost all early educators are women.

- 39% of the current TK-12 workforce are teachers of color (California Department of Education, 2020), reflecting a stark contrast to the demographic composition of both children and early educators.

Racial and Ethnic Identity of California Teachers and Children

ii Center-based early educators of color data from CSCCE analysis of the 2020 California Early Care and Education Workforce Study data.

iii Public school data from California Department of Education, 2020.

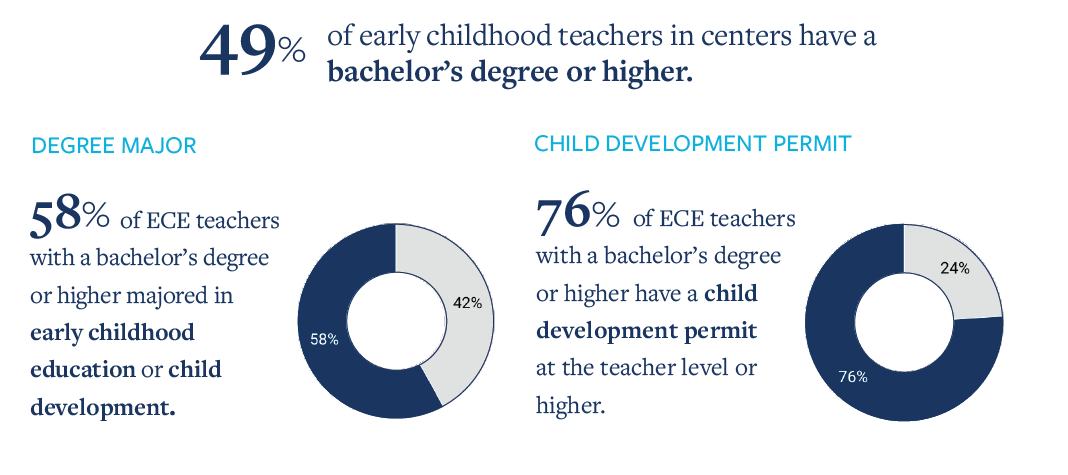

Experience and Education

- California’s center-based early childhood teachers have extensive practical experience, averaging 15 years of teaching children birth to age four.

- At least 37% of center-based teachers (about 31,000 teachers) meet or exceed the requirement for TK teachers to complete 24 college units in early childhood education.

Current TK Workforce

TK teachers are required to hold a Multiple Subject Teaching Credential with 24 units of early childhood education or a waiver/exemption from the unit requirement. For those who may qualify for a waiver or exemption, the credential alone historically has not included a focus on early education pedagogy (Austin et al., 2015). Findings from CSCCE’s exploratory TK survey suggest many TK teachers enter their jobs with less early childhood education and experience than the current ECE workforce.

Among TK teachers who responded to the survey, 90% have previous teaching experience in elementary grades K-3, however, far fewer have experience with younger children.

37% of TK teachers have previous teaching experience in ECE settings with children younger than five.

34% of TK teachers have an associate degree or higher in early childhood education or child development.

17% of TK teachers have a child development permit.

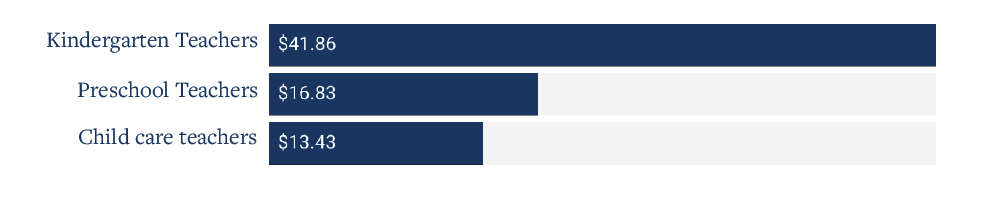

Risk of Widening California’s Existing ECE Wage Gaps

While nearly all early educators are poorly paid, there are disparities driven by a combination of public policy, funding, and systemic racism. The result is a system in which Black educators and those who work with the youngest children are systematically paid the least (Austin et al., 2019; Whitebook et al., 2018).

Wage Data

Median Hourly Wages of Early Educators in California

In California:

- Early educators with a bachelor’s degree are paid 38% less than TK-8 teachers (McLean et al., 2021);

- Early childhood teachers have a poverty rate of 17% (Gould et al., 2020), nearly seven times higher than K-8 teachers (McLean et al., 2021); and

- Black early educators experience poverty at as much as double the rates of their White peers (Gould et al., 2019).

Recommendations to Close the Equity Gap in TK Expansion

The concept of TK as a universal program holds promise. Transitional kindergarten represents a step toward early care and education being recognized as a universal public good, available to all, regardless of family income. Additionally, TK establishes the value of teaching four-year-olds on par with that of teaching older children and facilitates pay parity with K-3 teachers. However, current TK implementation proposals erect barriers for diverse, experienced, and prepared early educators to access these jobs (California Legislative Information, 2021b; California Legislative Information, 2021a). They also prevent established ECE programs from delivering public transitional kindergarten.

The architects of universal TK may not intend for this policy to be racist, but ultimately, the outcomes of the policy are what matter. California agencies and leaders responsible for TK implementation have the opportunity to exercise their authority to promote equity in early education employment and service delivery. Specifically, TK can be used to seed structural reforms necessary to ensure an effective and equitable ECE system. To this end, we offer the following recommendations.

Recommendations

1. Utilize the existing ECE system and qualified workforce that is already serving four-year-olds.

- Expand TK via the existing mixed-delivery system that is inclusive of public schools, nonprofits, center-based programs, and family child care programs, drawing upon the expertise, experience, and facilities that already exist.

- Assess the need for new teachers and spaces after maximizing the capacity of the existing delivery system.

2. Establish alternative pathways to obtain the Multiple Subject Teaching Credential to qualify as a TK teacher.

To support access to TK jobs for the existing ECE workforce:

- Create a route to the credential that accepts a bachelor’s and/or graduate degree in early childhood education or child development from an appropriately accredited institution as an approved subject-matter program, with three or more years of verified full-time teaching experience satisfying any practicum and/or student teaching experience. Such alternative pathways would eliminate the need for early educators to leave their current employment in order to satisfy full-time student teaching requirements. Similar opportunities already exist for K-12 teachers. The district intern credential is a model to build from (California Commission on Teacher Credentialing, 2021a).

To support an expanded and future workforce:

- In the short term, revive California’s existing standard early childhood credential for preschool through 3rd grade, with field experience and residencies focused on this specific age group (California Commission on Teacher Credentialing, 2014). In the long term, revise the credential to reflect the birth-to-age-eight continuum of learning and development; and

- Ensure that residency models include specific options that focus clinical practice and mentorship in an ECE context (California Commission on Teacher Credentialing, 2021b).

3. Implement and fund strategies to eradicate barriers to obtaining higher education and credentials.

- Provide grants to preparation programs so they can effectively serve populations that have been marginalized from higher education;

- Provide scholarships and fee/tuition waivers to ensure that members of the current and future workforce have opportunities and supports to acquire education and training at no personal financial cost; and

- Include targeted opportunities and supports for people of color as well as individuals who speak English as a second language.

4. Establish and fund compensation parity for TK teachers, regardless of setting.

- Articulate a compensation parity policy with K-3 teachers that reflects full parity and includes salary, benefits, and payment for professional responsibilities (Whitebook & McLean, 2017).

5. Establish a set of equity indicators for measuring the impact of public ECE policies on educators, children, and families.

Equity indications should be developed in concert with the early education workforce (center teachers and administrators, family child care providers, and TK teachers), parents, and key stakeholders. Such stakeholders should be more diverse than the existing state committees, which include few practitioners.

- Enact required participation in state workforce data systems by all members of the ECE and TK workforce employed in schools, center- and home-based child care settings; and

- Fund and require ongoing data collection, analysis, and reporting in order to:

- Assess the impact of TK expansion and other ECE policies on the workforce and delivery system across settings and ages of children;

- Identify disparities in such areas as compensation, educational attainment, and tenure according to, for example, race, age, and geography; and

- Inform local and state policy, implementation, and decision making.

References

Austin, L.J.E., Edwards, B., Chavez, R., & Whitebook, M. (2019). Racial Wage Gaps in Early Education Employment. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. https://cscce.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/RacialWageGaps-Early-Education-Brief.pdf

Austin, L.J.E., Whitebook, M., Kipnis, F., Sakai, L., Amanta, F., & Abbasi, F. (2015). Teaching the Teachers of Our Youngest Children: The State of Early Childhood Higher Education in California, 2015. Highlights. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. https://cscce. berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/TeachingTeachers_California-Highlights-2015.pdf

California Commission on Teacher Credentialing. (2014). Early Childhood Credentials/Permits Issued by the Commission. https://www.ctc.ca.gov/docs/default-source/educator-prep/early-care-files/child- development-permit-master.pdf?sfvrsn=aed6cedb_0

California Commission on Teacher Credentialing. (2021a). District Intern Credential. https://www.ctc.ca.gov/ credentials/leaflets/district-intern-credential-(cl-707b)

California Commission on Teacher Credentialing. (2021b). Teacher Residency Grant Program. https://www. ctc.ca.gov/educator-prep/grant-funded-programs/teacher-residency-grant-program

California Department of Education. (2020). Fingertip facts on education in California. https://www.cde. ca.gov/ds/ad/ceffingertipfacts.asp

California Legislative Information. (2021a). AB-22 Childcare: Preschool programs and transitional kindergarten: Enrollment: Funding. Retrieved August 3, 2021, from https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/ faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=202120220AB22

California Legislative Information. (2021b). AB-130 Education finance: Education omnibus budget trailer bill. https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=202120220AB130

Gould, E., Whitebook, M., Mokhiber, Z., & Austin, L.J.E. (2020). Financing Early Educator Quality: A Values- Based Budget for Every State. Economic Policy Institute, Washington, DC, and Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley.https://cscce.berkeley.edu/financing-early- educator-quality-a-values-based-budget-for-every-state/

Gould, E., Whitebook, M., Mokhiber, Z., & Austin, L.J.E. (2019). Breaking the silence on early child care and education costs: A values-based budget for children, parents, and teachers in California. Economic Policy Institute, Washington, DC, and Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. https://cscce.berkeley.edu/breaking-the-silence-on-costs/

KIDS COUNT Data Center. (2020). Child population by race and age group in California. KIDS COUNT Data Center. https://datacenter.kidscount.org/data/ tables/8446-child-population-by-race-and-age-group?loc=6&loct=2#detailed/2/6/fal se/1729,37,871,870,573,869,36,868,867,133/68,69,67,12,70,66,71|63,30/17077,17078

McLean, C., Austin, L.J.E., Whitebook, M., & Olson, K.L. (2021). Early Childhood Workforce Index – California State Profile. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. https:// cscce.berkeley.edu/workforce-index-2020/states/california/

Whitebook, M., & McLean, C. (2017). In Pursuit of Pre-K Parity: A Proposed Framework for Understanding and Advancing Policy and Practice. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley and the National Institute for Early Education Research. https://cscce.berkeley.edu/ wp-content/uploads/2017/04/in-pursuit-of-pre-k-parity.pdf

Whitebook, M., McLean, C., Austin, L.J.E., & Edwards, B. (2018). Early Childhood Workforce Index – 2018. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. https://cscce. berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Early-Childhood-Workforce-Index-2018.p

Suggested Citation

Williams, A., Montoya, E., Kim, Y., & Austin, L.J.E. (2021). New Data Shows Early Educators Equipped to Teach TK. Berkeley, CA: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. https://cscce.berkeley.edu/publications/data-snapshot/early-educators-equipped-to-teach-tk/

Acknowledgements

This paper was produced with grants from the Heising-Simons Foundation, First 5 California, and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation.

We extend many thanks to CSCCE staff members Marcy Whitebook, Hopeton Hess, Claudia Alvarenga, Penelope Whitney, and Ana Fox-Hodess for their contributions in reviewing and assisting with the preparation of this document.

This paper draws upon findings from the California Early Care and Education Workforce Study, a multi- year project generously supported by First 5 California, California Department of Education, the Heising- Simons Foundation, and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, and implemented in partnership with the California Child Care Resource & Referral Network.

The views presented in this report are those of the authors and may not reflect the views of the report’s funders or those acknowledged for lending their expertise or providing input.

Editor: Deborah Meacham